Swarm (Geomagnetic LEO Constellation)

EO

ESA

CNES

Operational (extended)

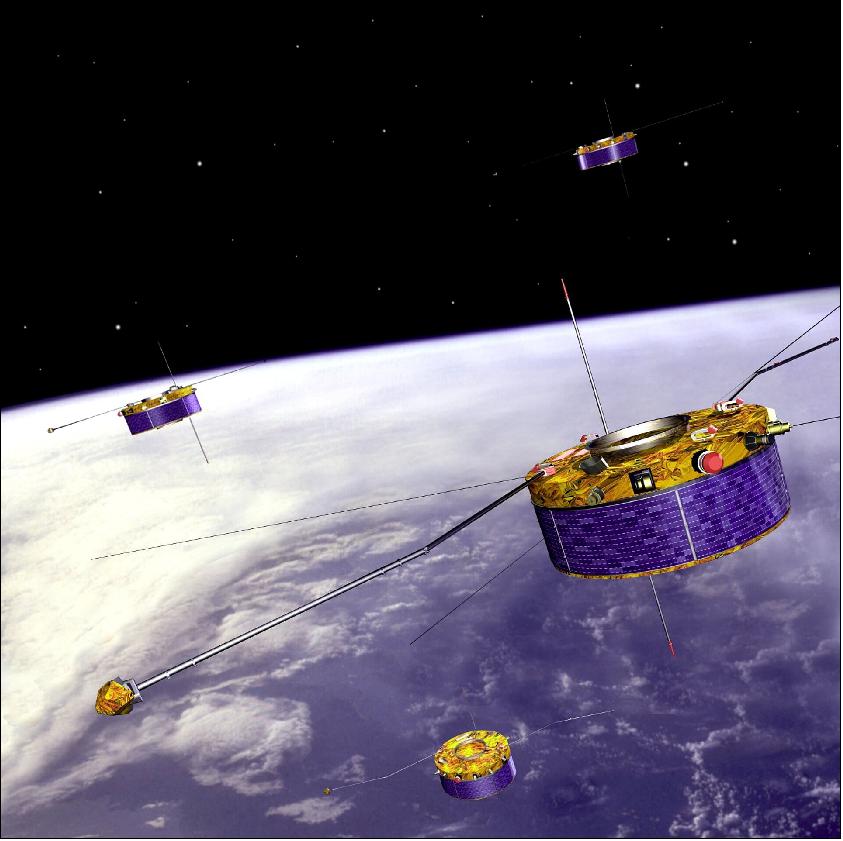

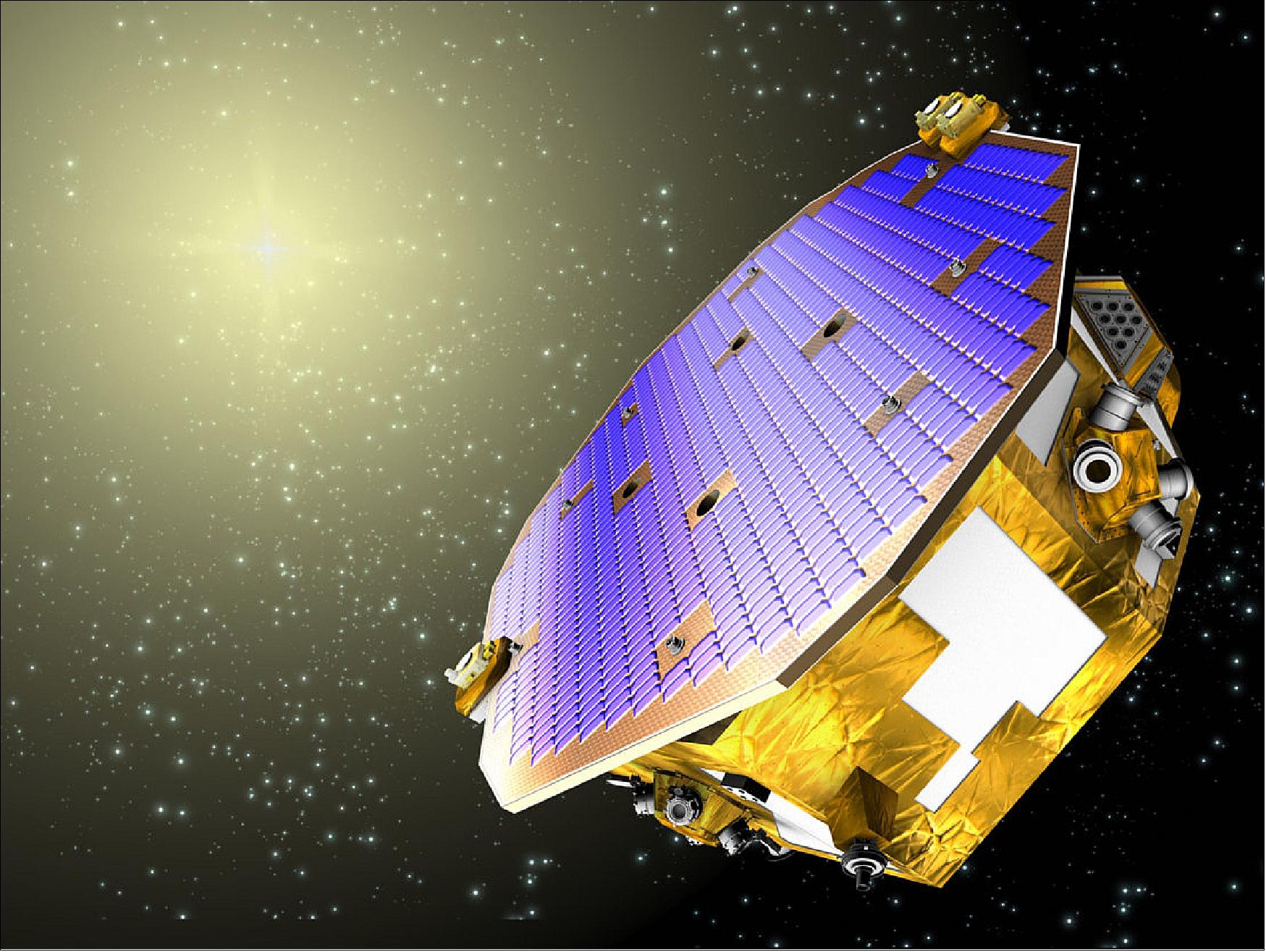

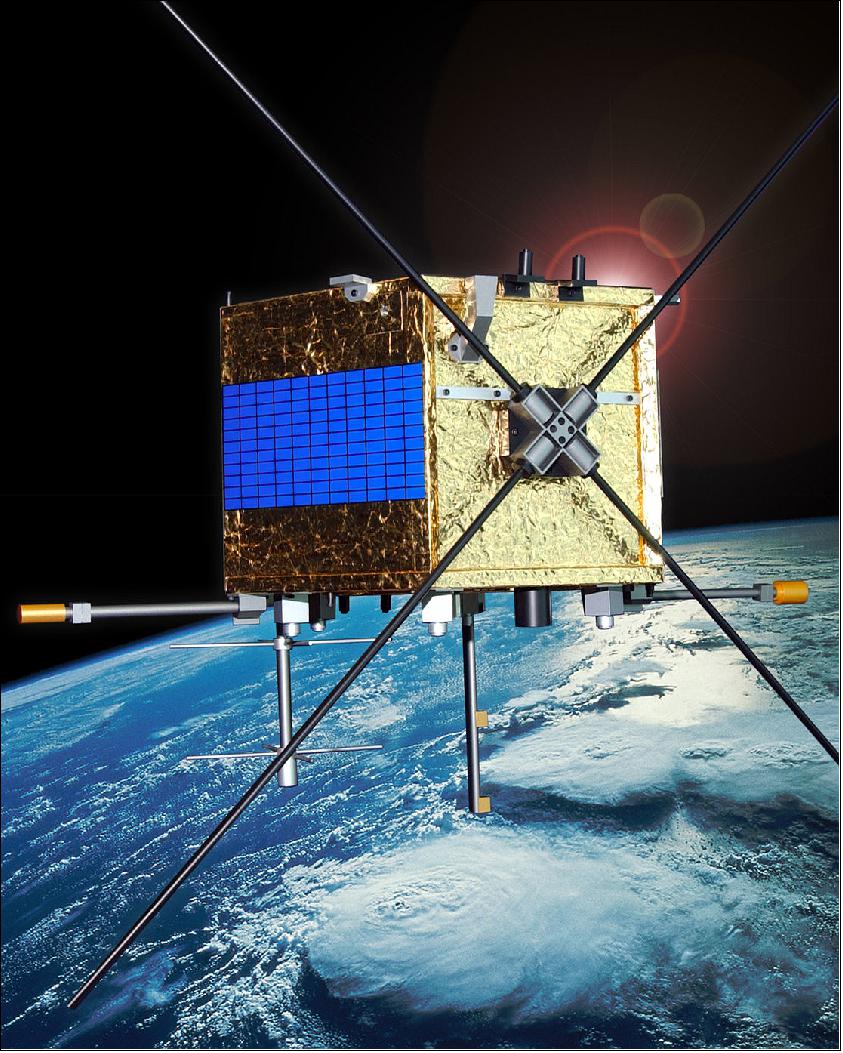

Launched in November 2013, Swarm is a constellation of three satellites operated by the European Space Agency (ESA) with the purpose of mapping Earth’s magnetic field.

Quick facts

Overview

| Mission type | EO |

| Agency | ESA, CNES, CSA |

| Mission status | Operational (extended) |

| Launch date | 22 Nov 2013 |

| Measurement domain | Gravity and Magnetic Fields |

| Measurement category | Gravity, Magnetic and Geodynamic measurements |

| Measurement detailed | Magnetic field (scalar), Magnetic field (vector), Gravity field, Electric Field (vector) |

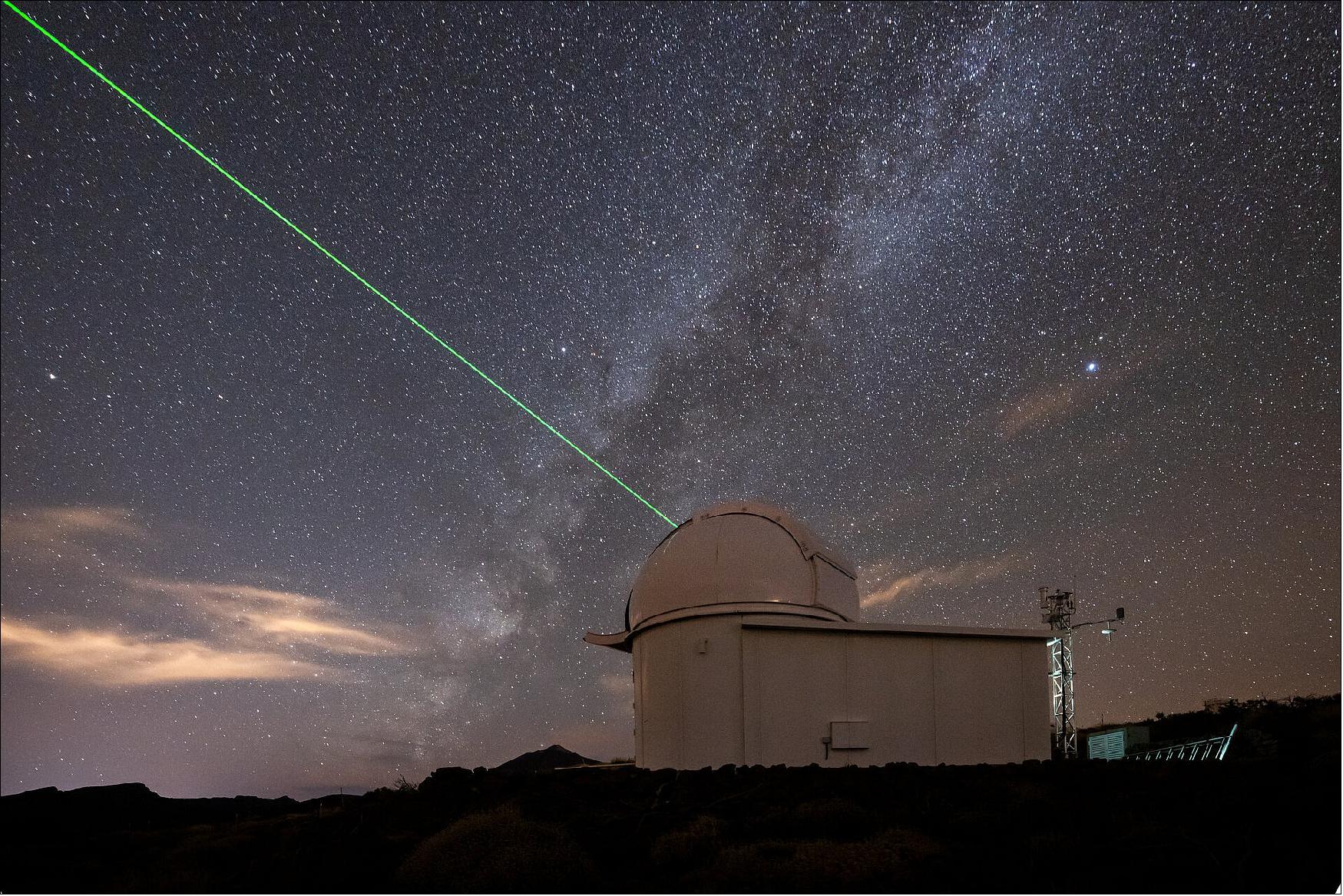

| Instruments | Laser Reflectors (ESA), STR, ACC, GPS Receiver (Swarm), EFI, ASM, VFM |

| Instrument type | Space environment, Magnetic field, Precision orbit |

| CEOS EO Handbook | See Swarm (Geomagnetic LEO Constellation) summary |

Related Resources

Summary

Mission Capabilities

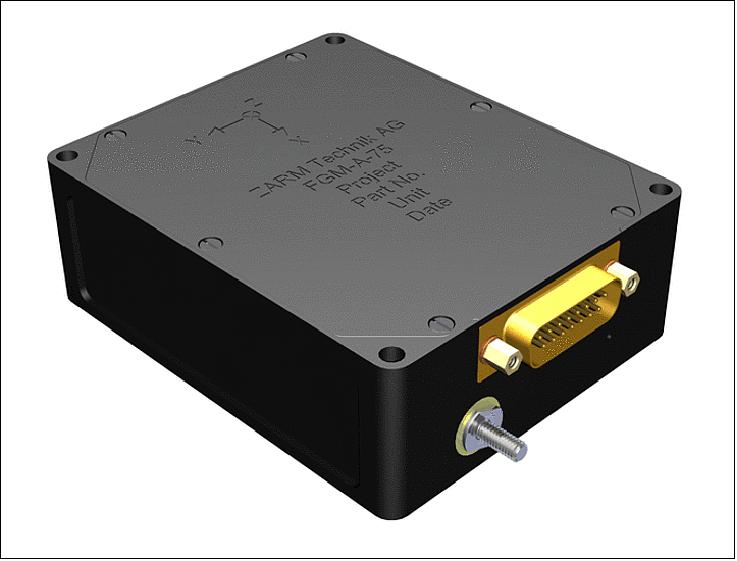

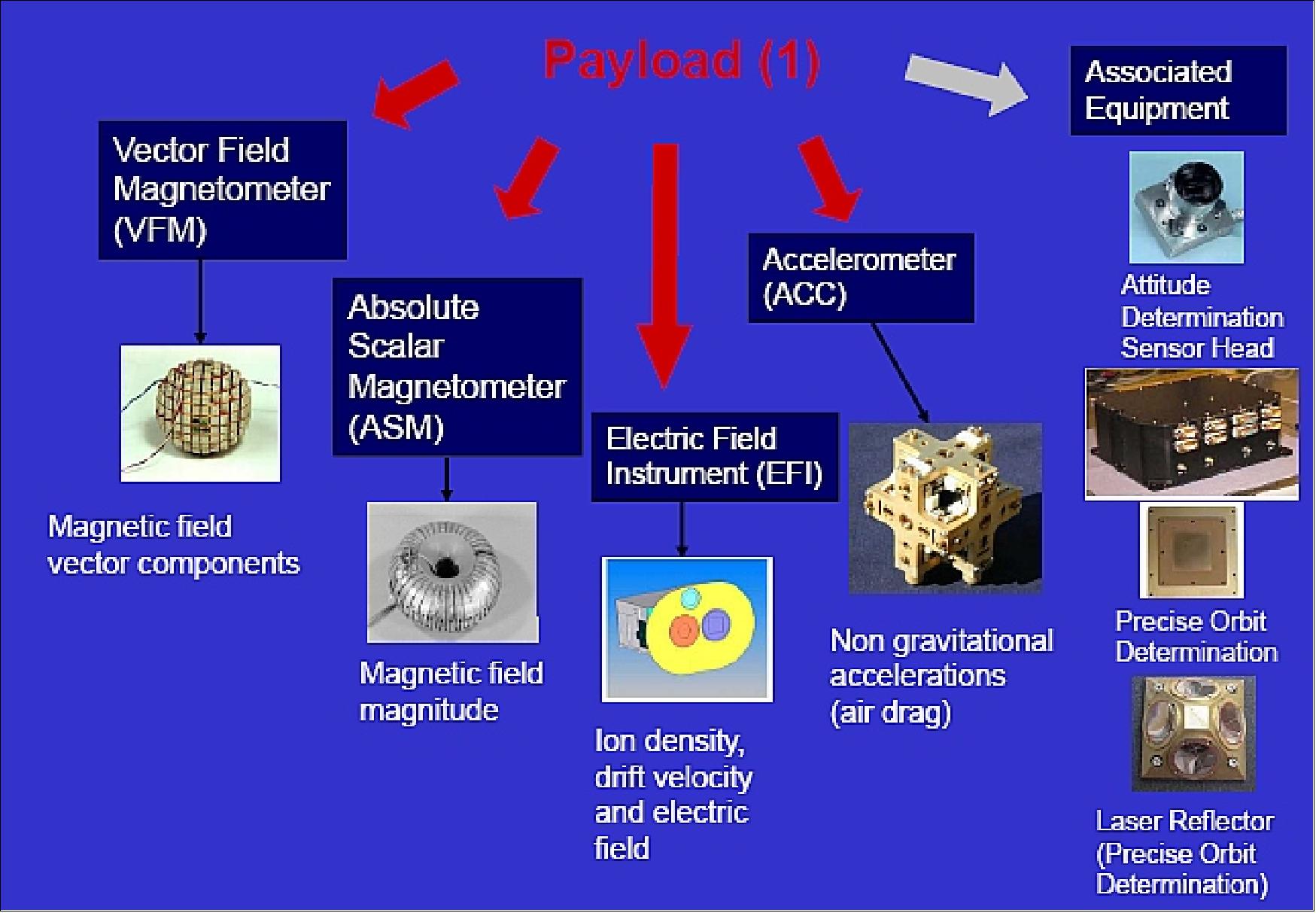

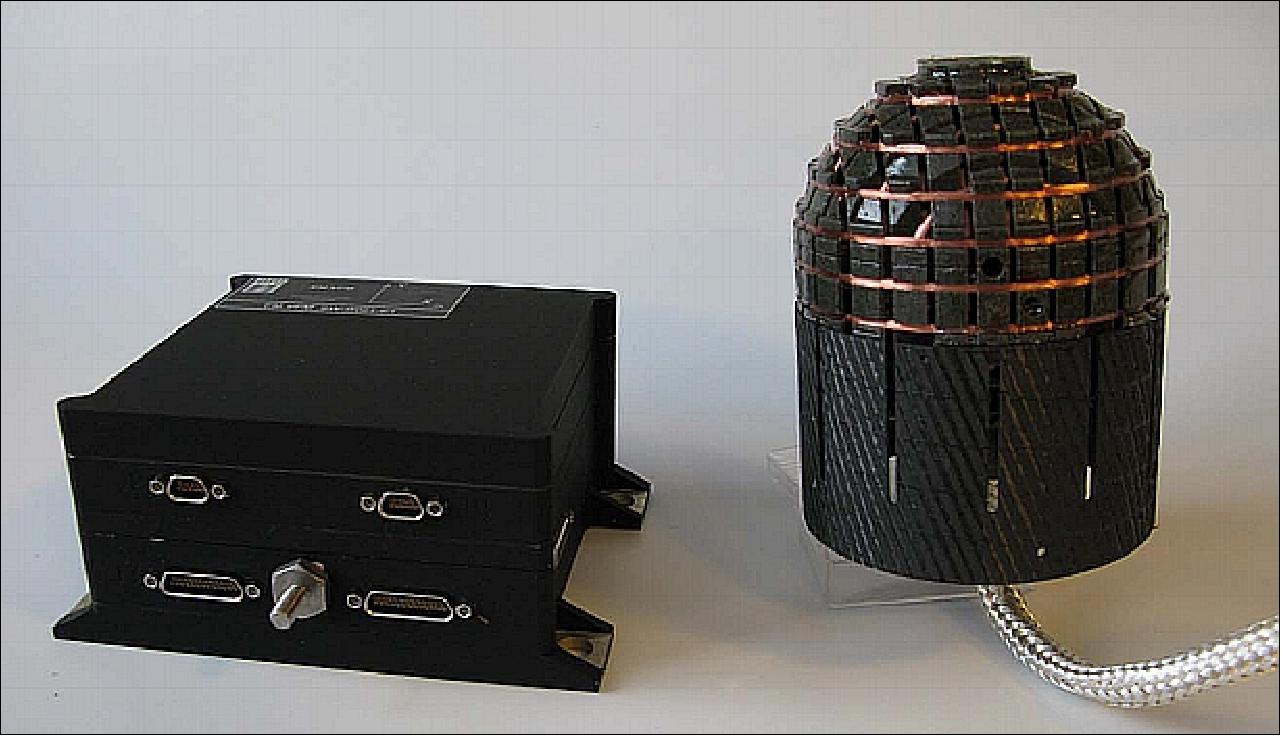

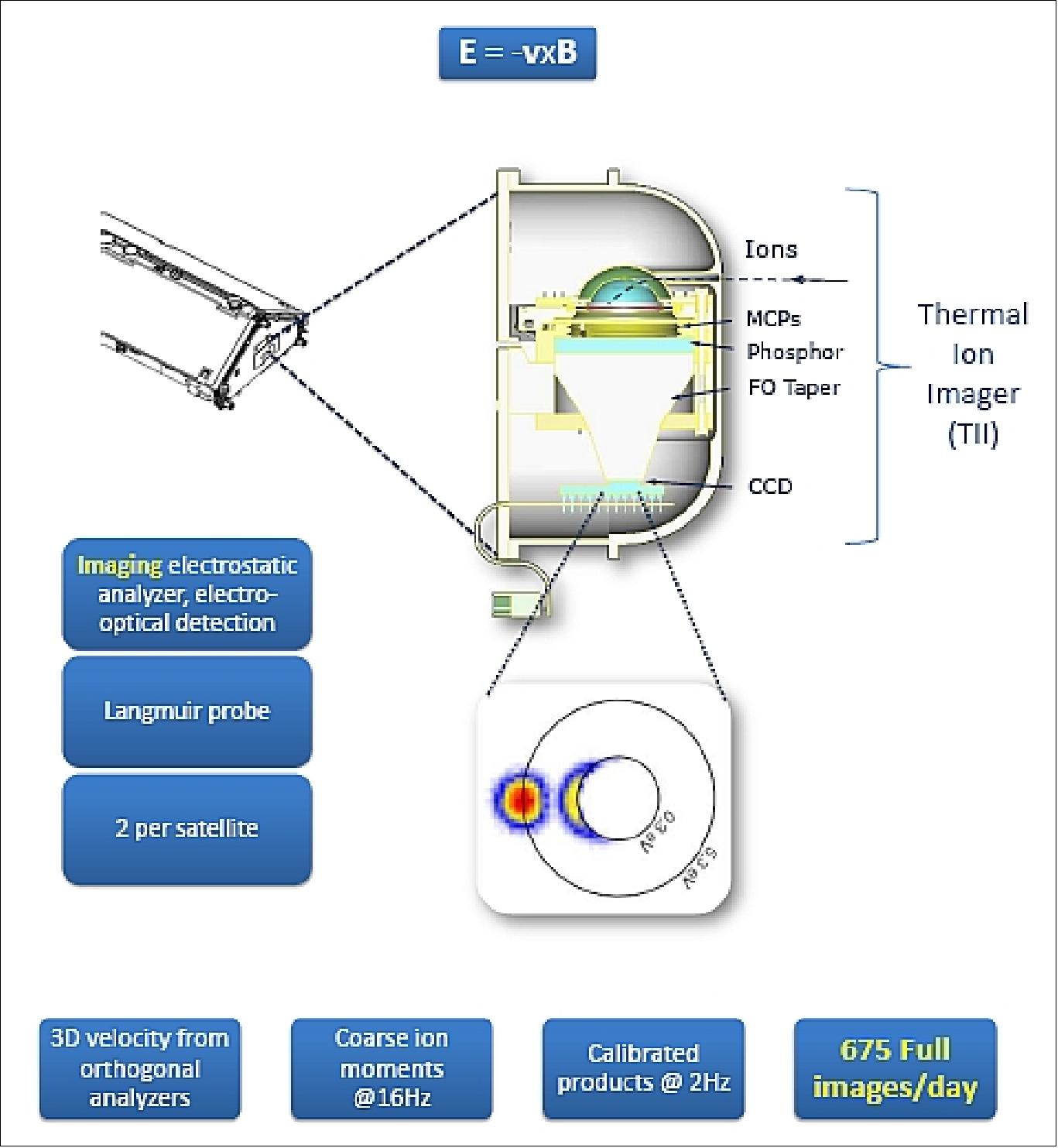

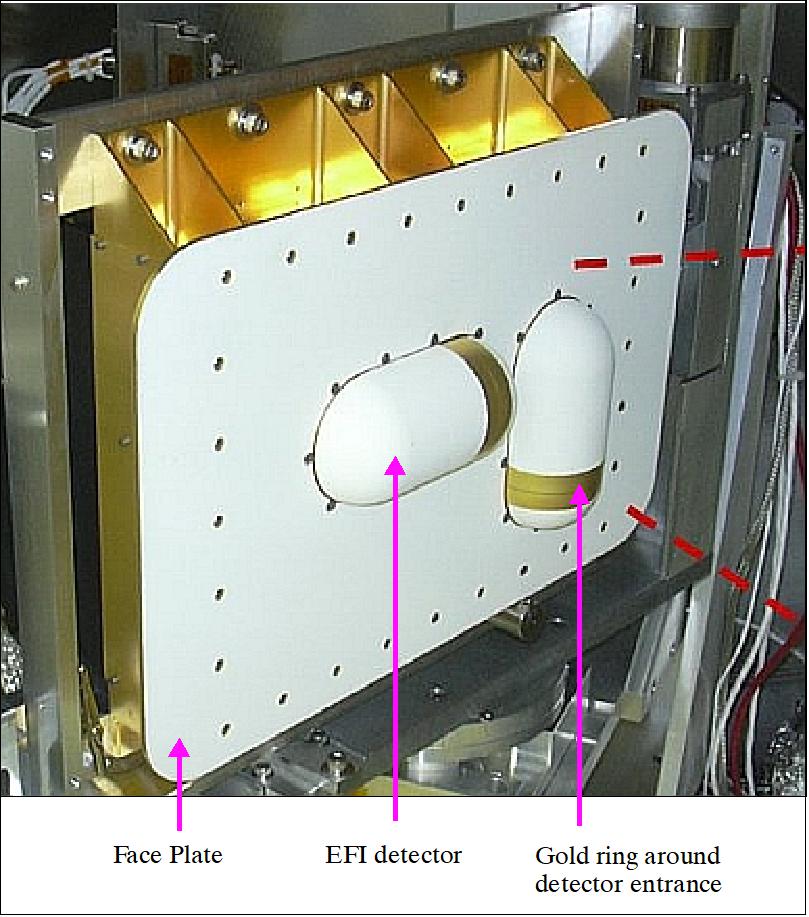

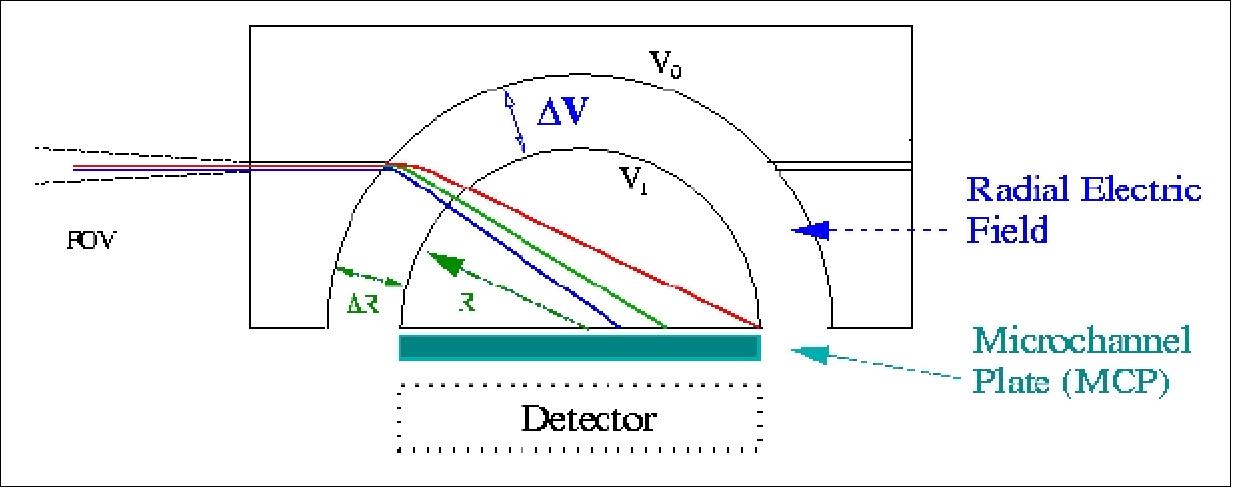

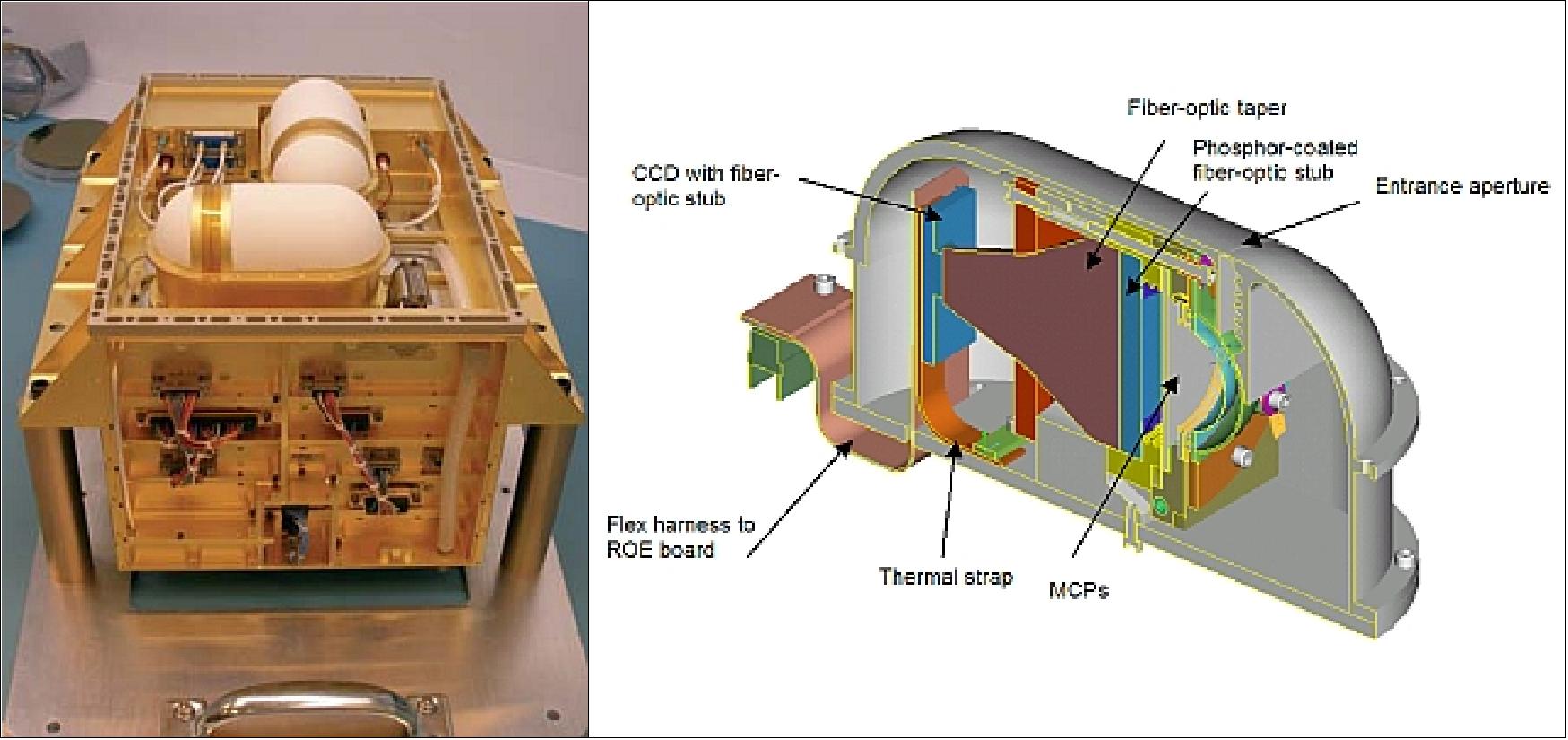

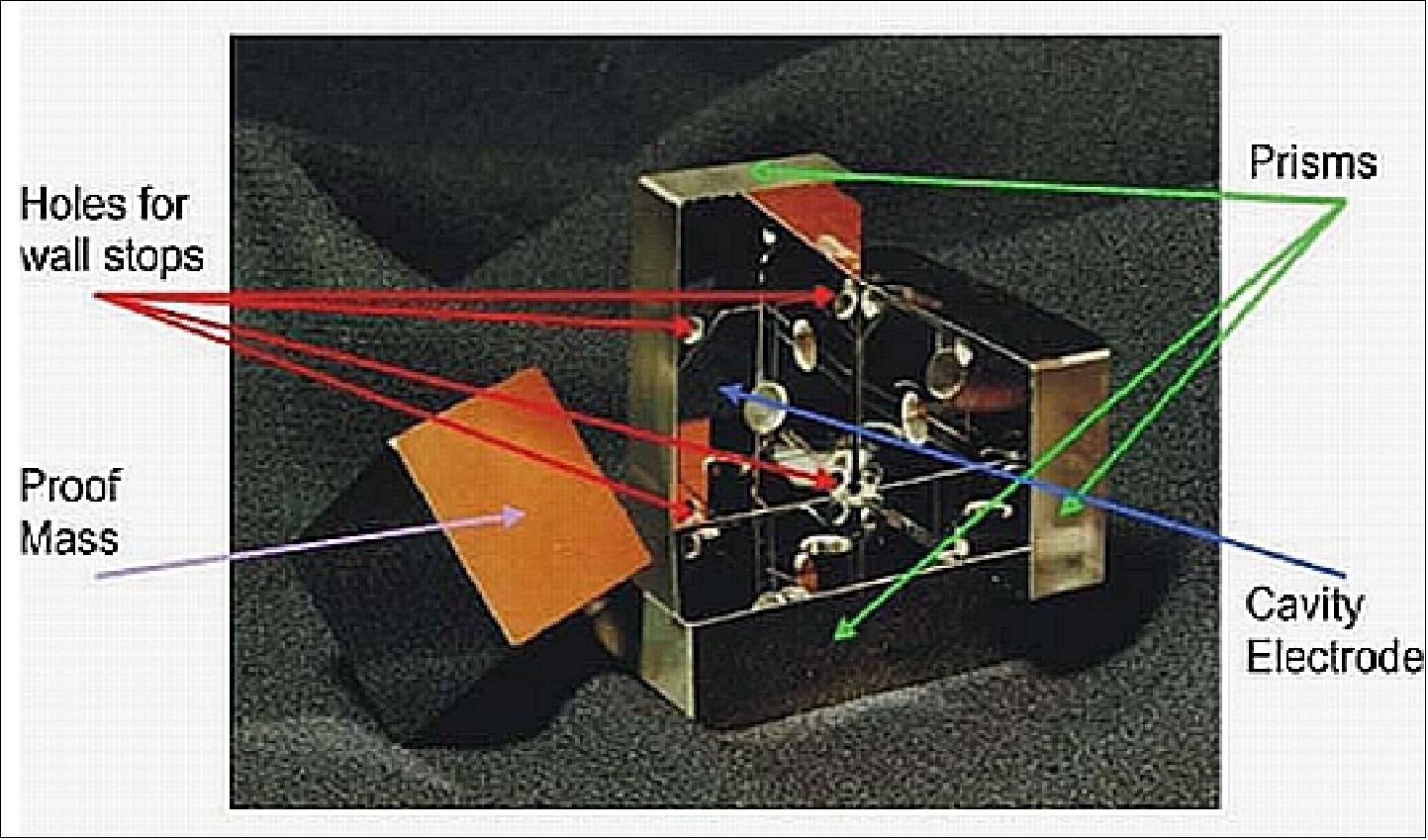

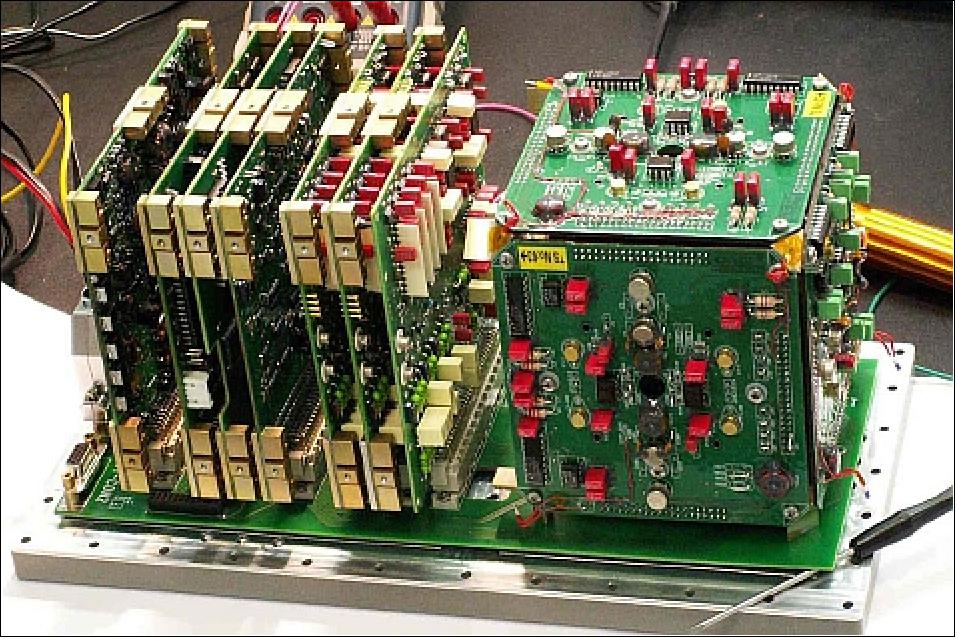

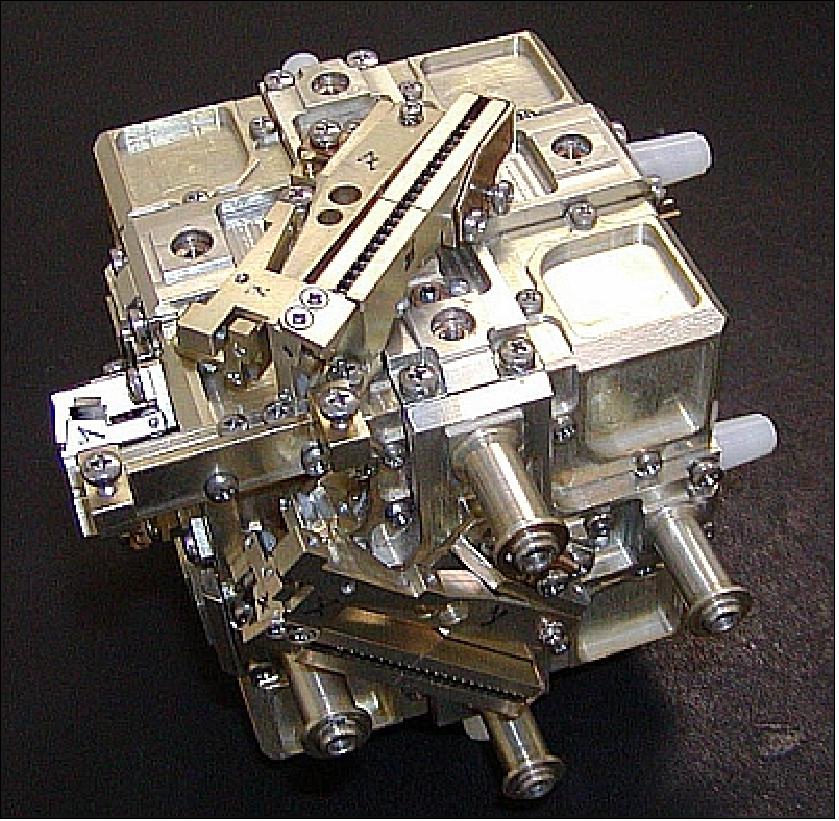

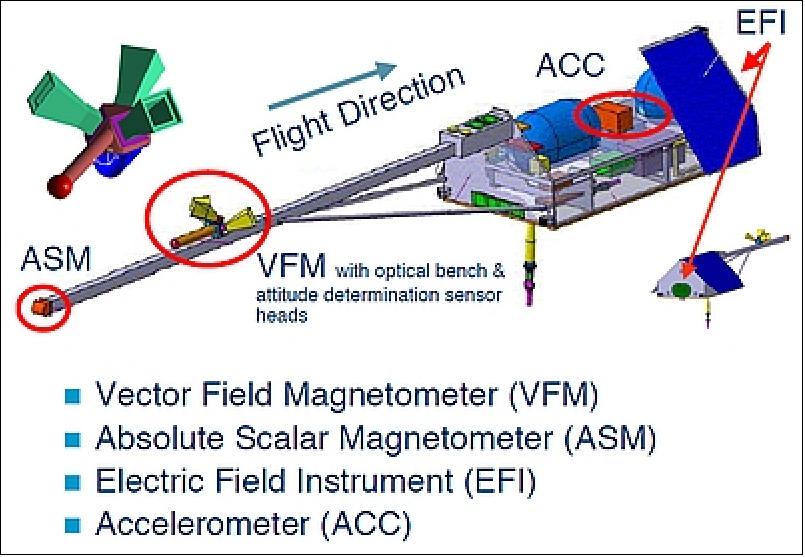

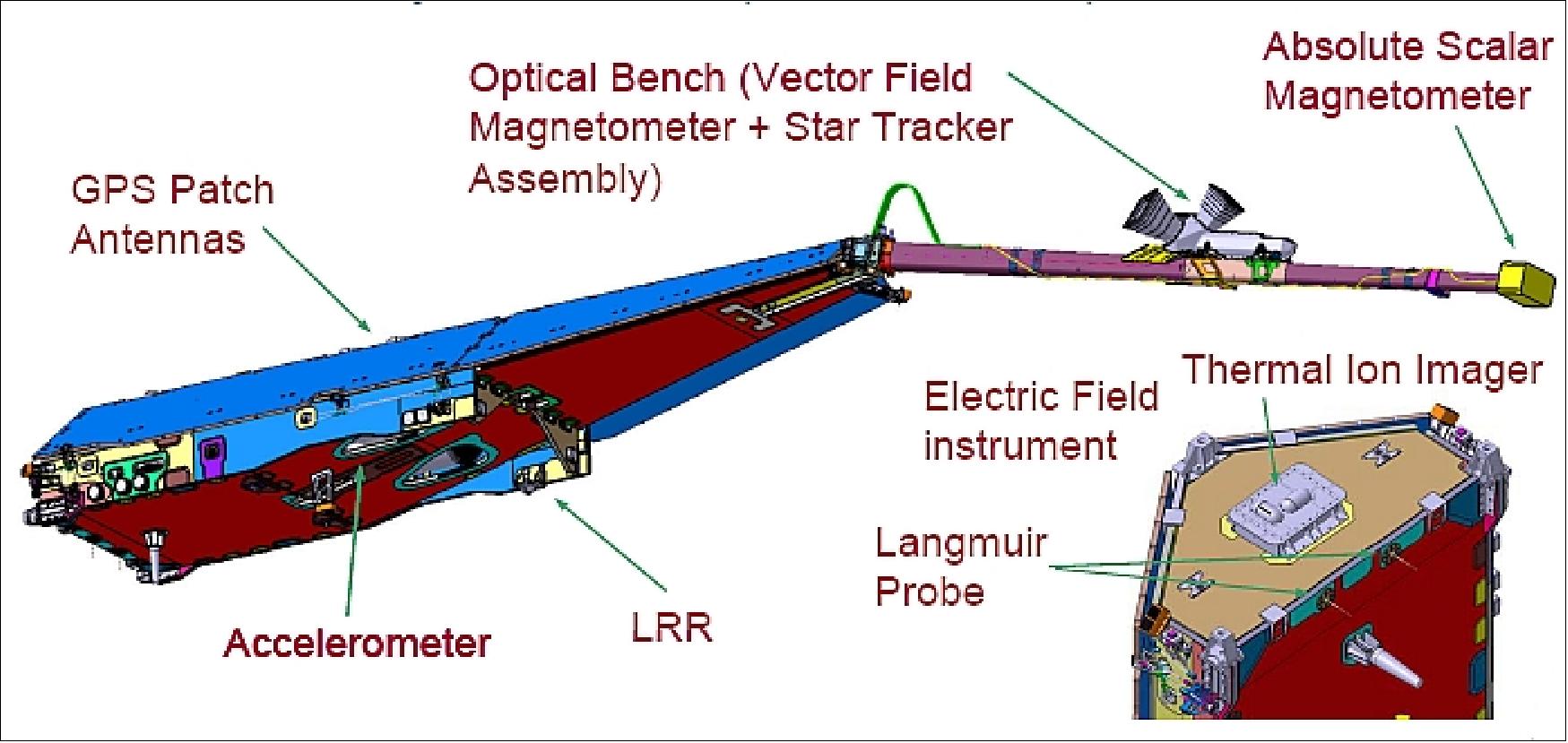

All three Swarm satellites carry the same instruments: a Vector Field Magnetometer (VFM) that measures the direction of the magnetic field; an Absolute Scalar Magnetometer (ASM) that measures the strength of the magnetic field; an Electric Field Instrument (EFI) that measures the plasma density, drift, and acceleration; as well as a Micro Accelerometer-04 (MAC-04) that measures the air drag, winds, Earth albedo, and solar radiation pressure.

Performance Specifications

VFM has a sampling rate of 50 Hz, and ASM has an absolute accuracy of less than 0.3 nT.

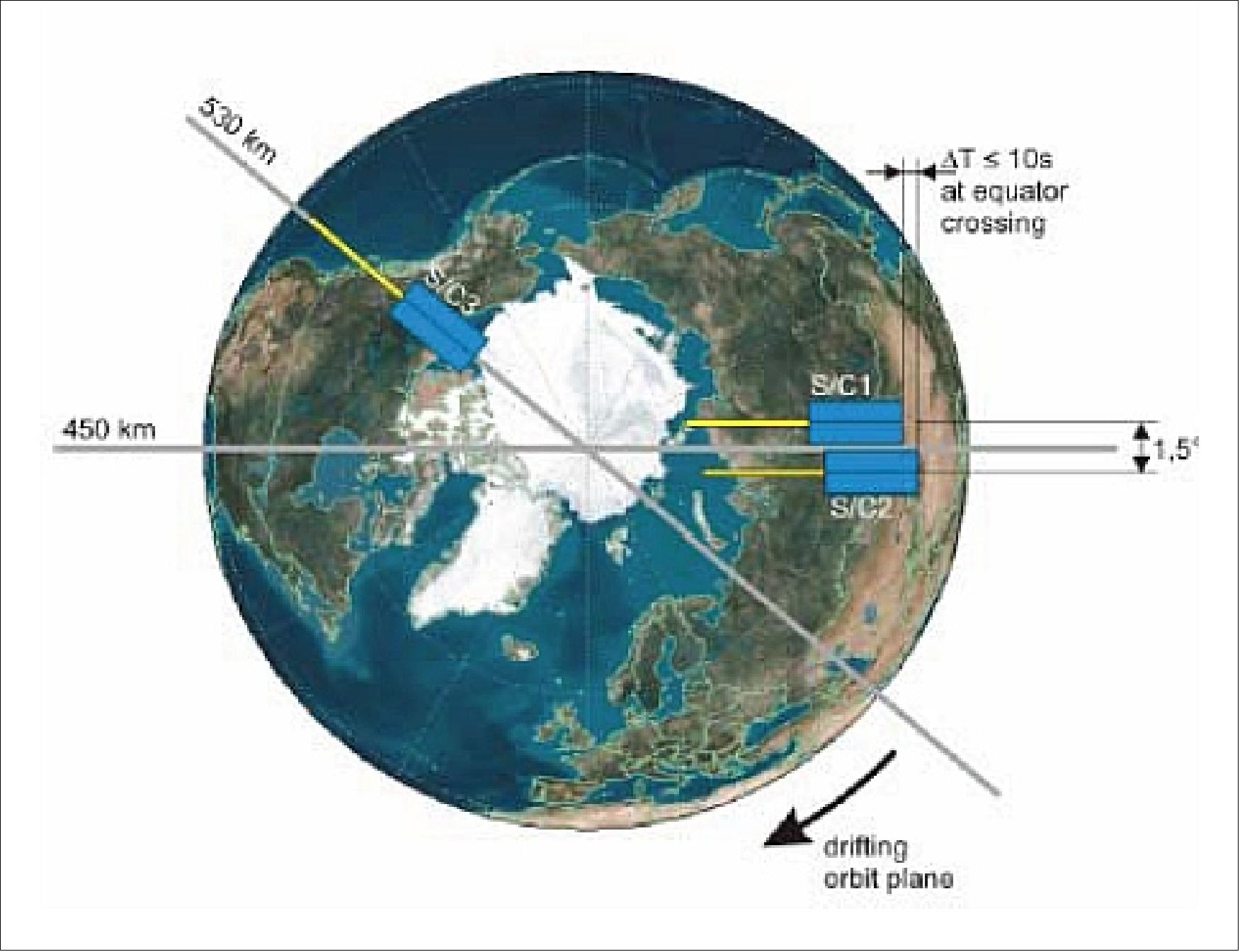

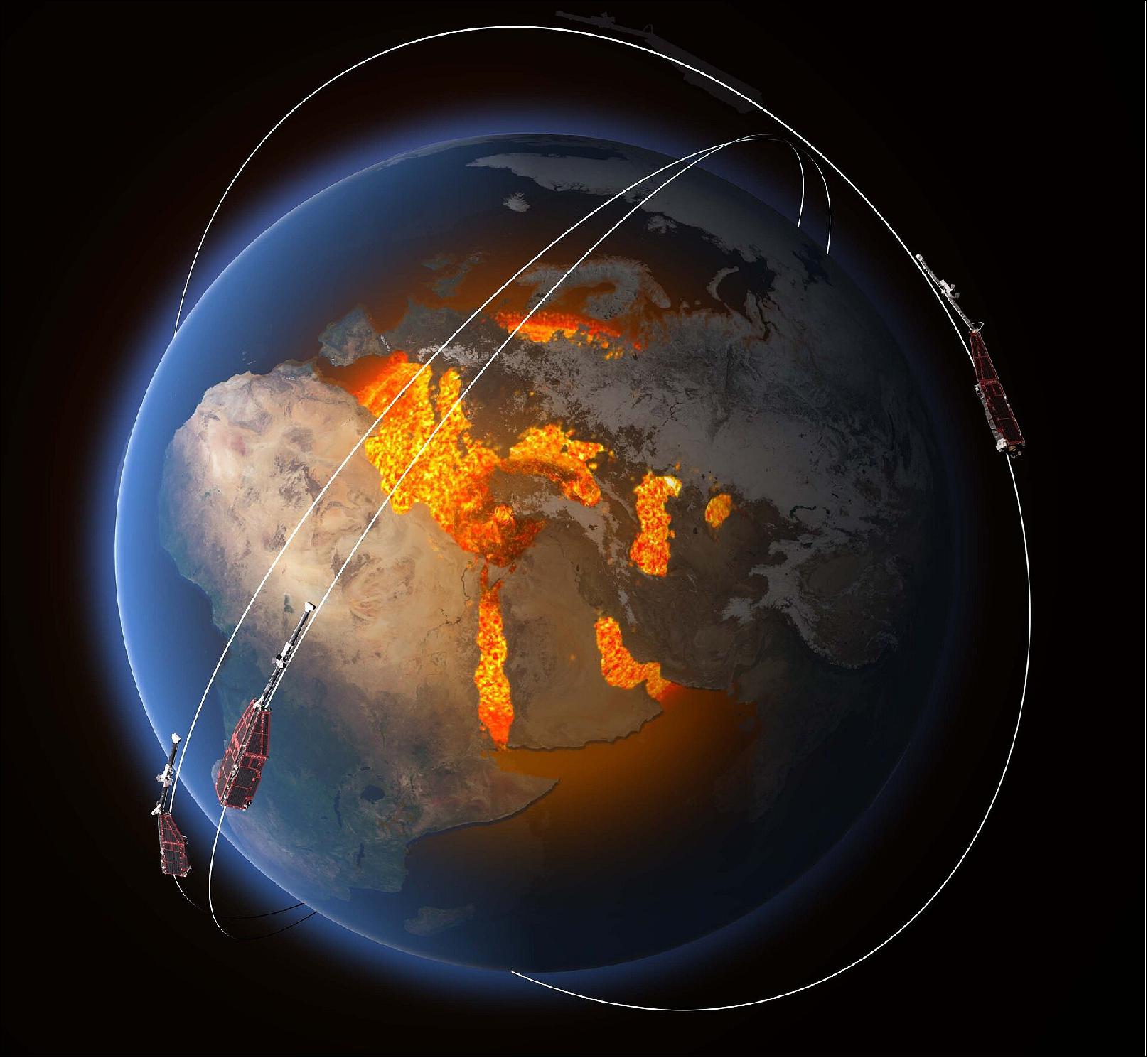

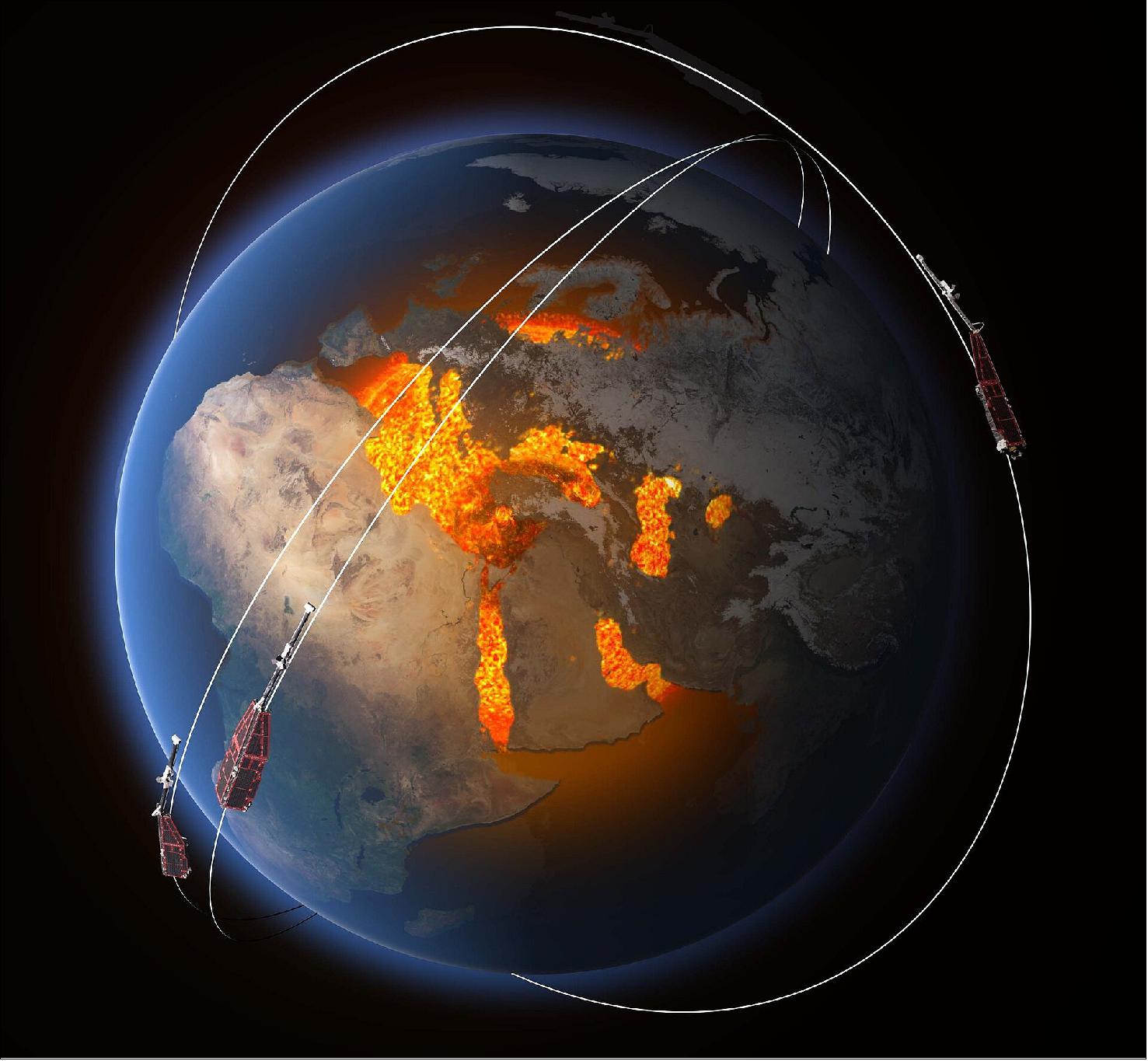

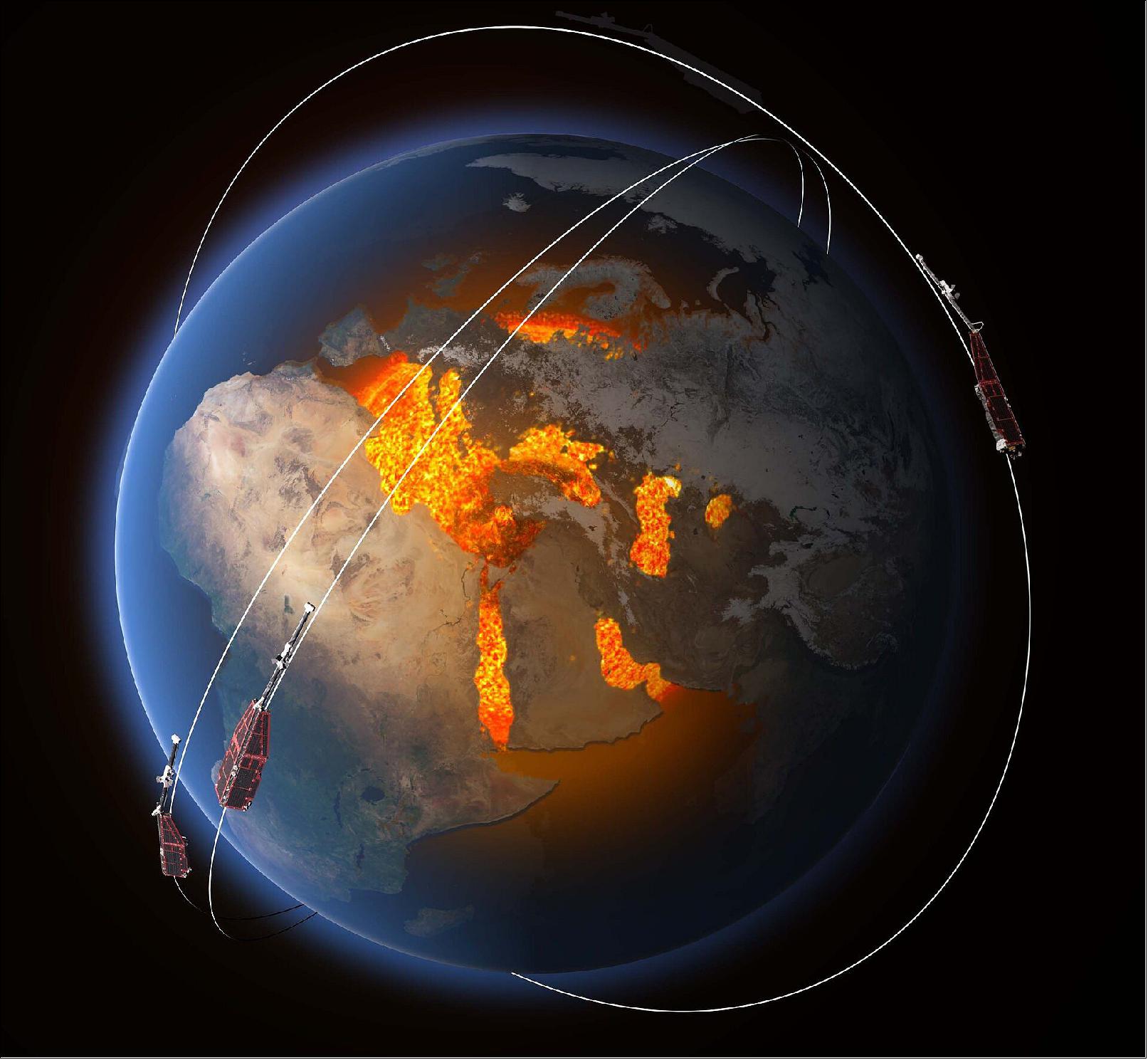

The first and third satellites, Swarm-A and Swarm-C, share the same non-sun-synchronous orbit with an altitude of 450 km and an inclination of 87.4°. They travel in parallel with an east-west separation of 1-1.5° and an orbital time difference of fewer than 10 seconds. The second satellite, Swarm-B, maintains a non-sun-synchronous orbit with an altitude of 530 km and an inclination of 88°.

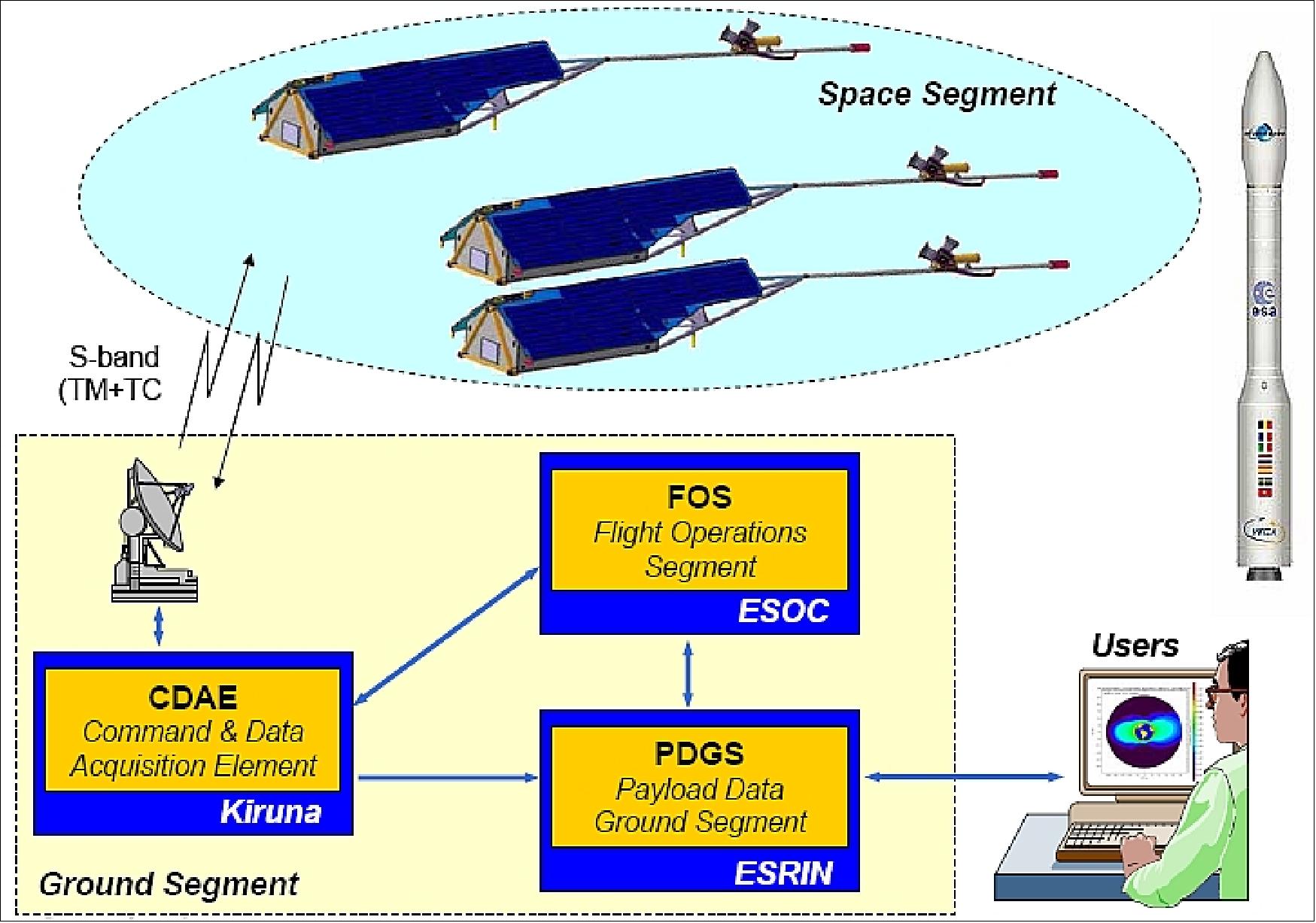

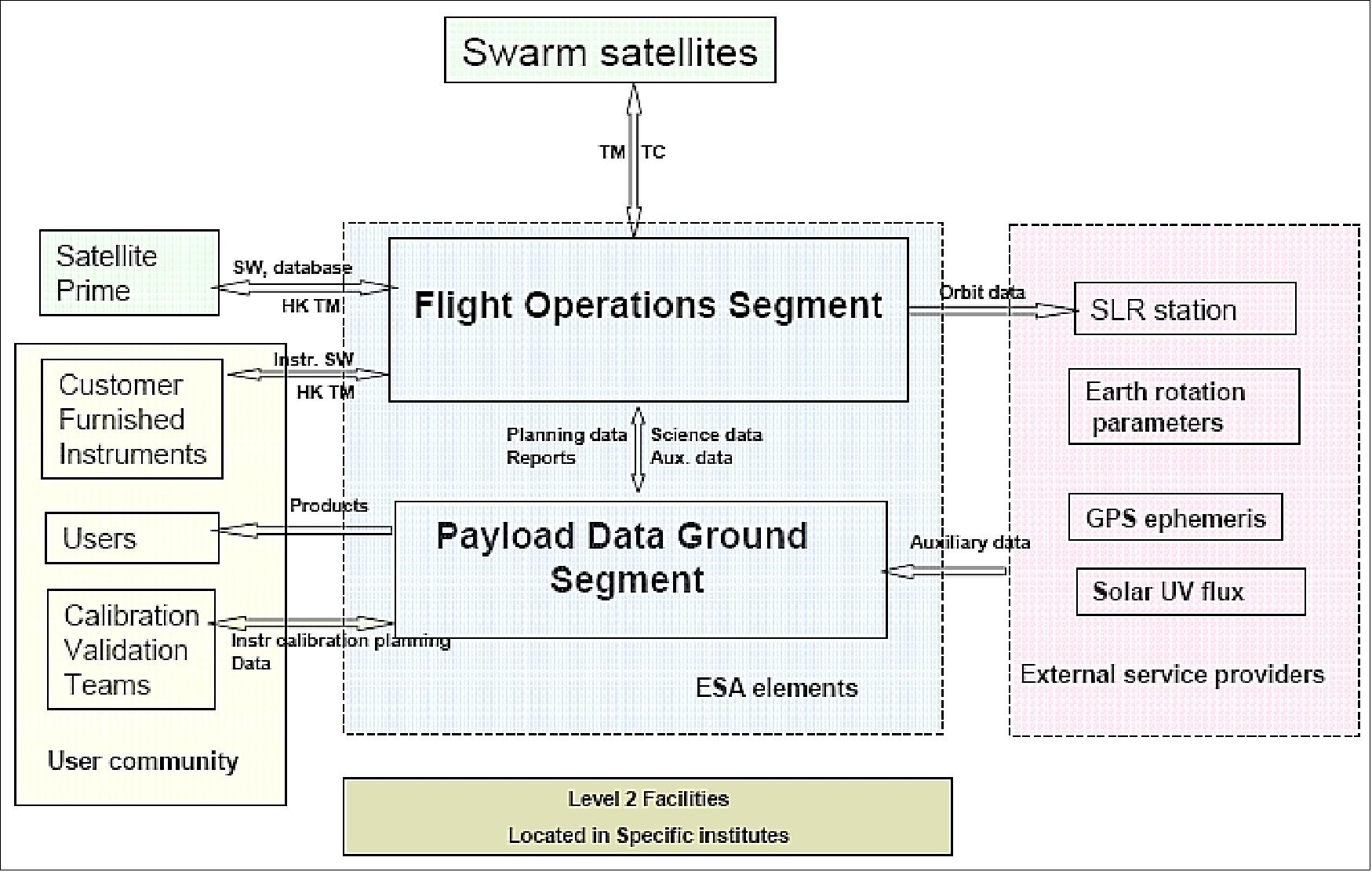

Space & Hardware Components

Communications are performed via S-band radio frequency for Telemetry, Tracking, and Command (TT&C) as well as data transmission; the downlink data rate is 6 Mbit/s and the uplink rate is 4 kbits/s.

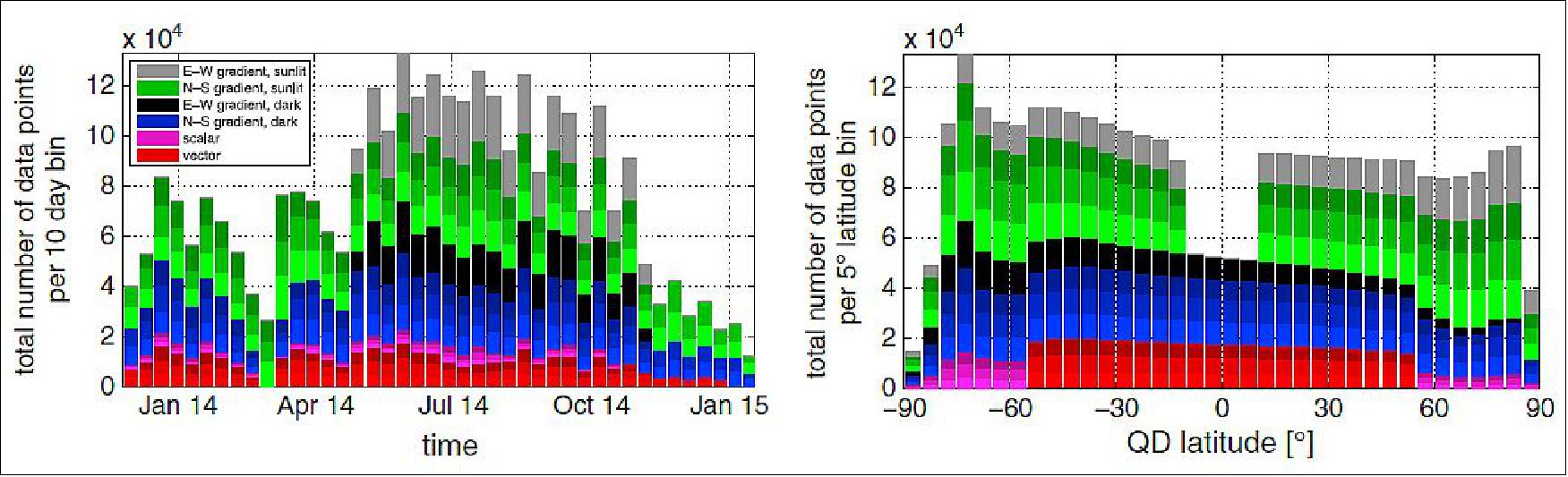

The different orbits taken by the Swarm constellation optimise the sampling in space and time to distinguish different magnetic sources and their strengths.

Swarm (Geomagnetic LEO Constellation)

Space segment concept Launch Swarm's Orbits Mission Status Sensor ComplementGround Segment References

Swarm is a minisatellite constellation mission within the Earth Explorer Opportunity Program of ESA, proposed under the lead of DNSC (Danish National Space Center) of Copenhagen, Denmark (formerly DSRI). In January 2007, DNSC became DTU Space, an institute at the Technical University of Denmark. The Swarm mission will be the 4th mission in ESA's Earth Explorer Program, following GOCE, SMOS, and CryoSat-2.

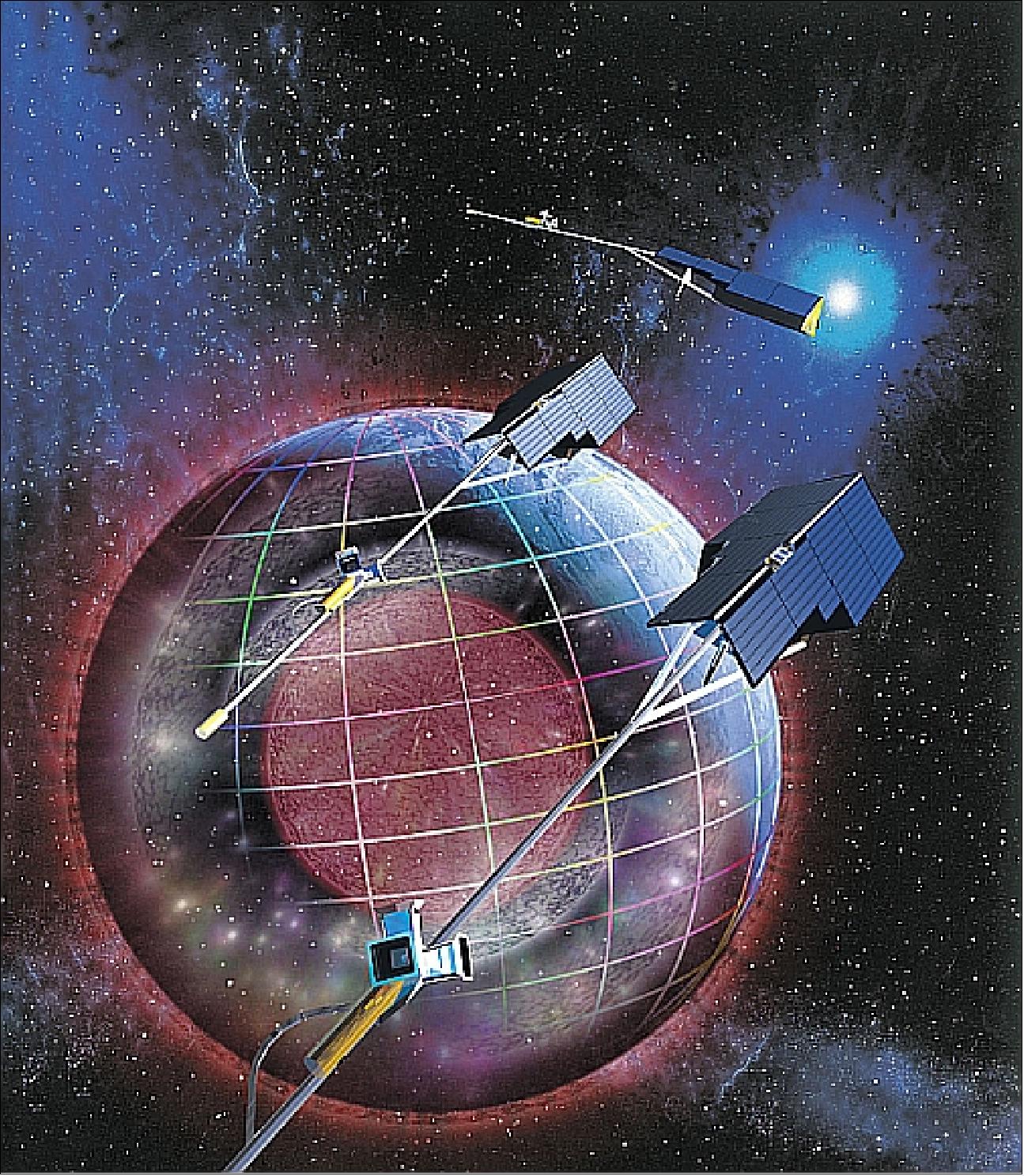

The first mission to ever map the Earth's magnetic field vector at LEO was the NASA MagSat spacecraft (launch Oct. 30 1979). Due to the low perigee (perigee=350 km, apogee=551 km), MagSat remained in orbit for only seven and a half months until June 11, 1980. About 20 years later, the Danish Ørsted micro satellite (1999-), the German CHAMP (2000-), the Argentine SAC-C (2000-) have been designed specifically for mapping the LEO magnetic field. Common to these recent missions is the magnetometry package, which utilizes a vector field magnetometer co-mounted with a star tracker (2 in the case of CHAMP) on an optical bench. As the accuracy of the instrument package has constantly increased, as well as the modelling methods have been improved towards optimized signal decomposition, it has been realized that simultaneous data from several points in space is needed, if the ultimate modelling barrier, the spatial-temporal ambiguity, has to be broken.

The overall objective of the Swarm mission is to build on the Ørsted and CHAMP mission experiences and to provide the best ever survey of the geomagnetic field (multi-point measurements) and its temporal evolution, to gain new insights into the Earth system by improving our understanding of the Earth's interior and climate. 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) 8) 9) 10) 11) 12) 13) 14) 15) 16) 17) 18)

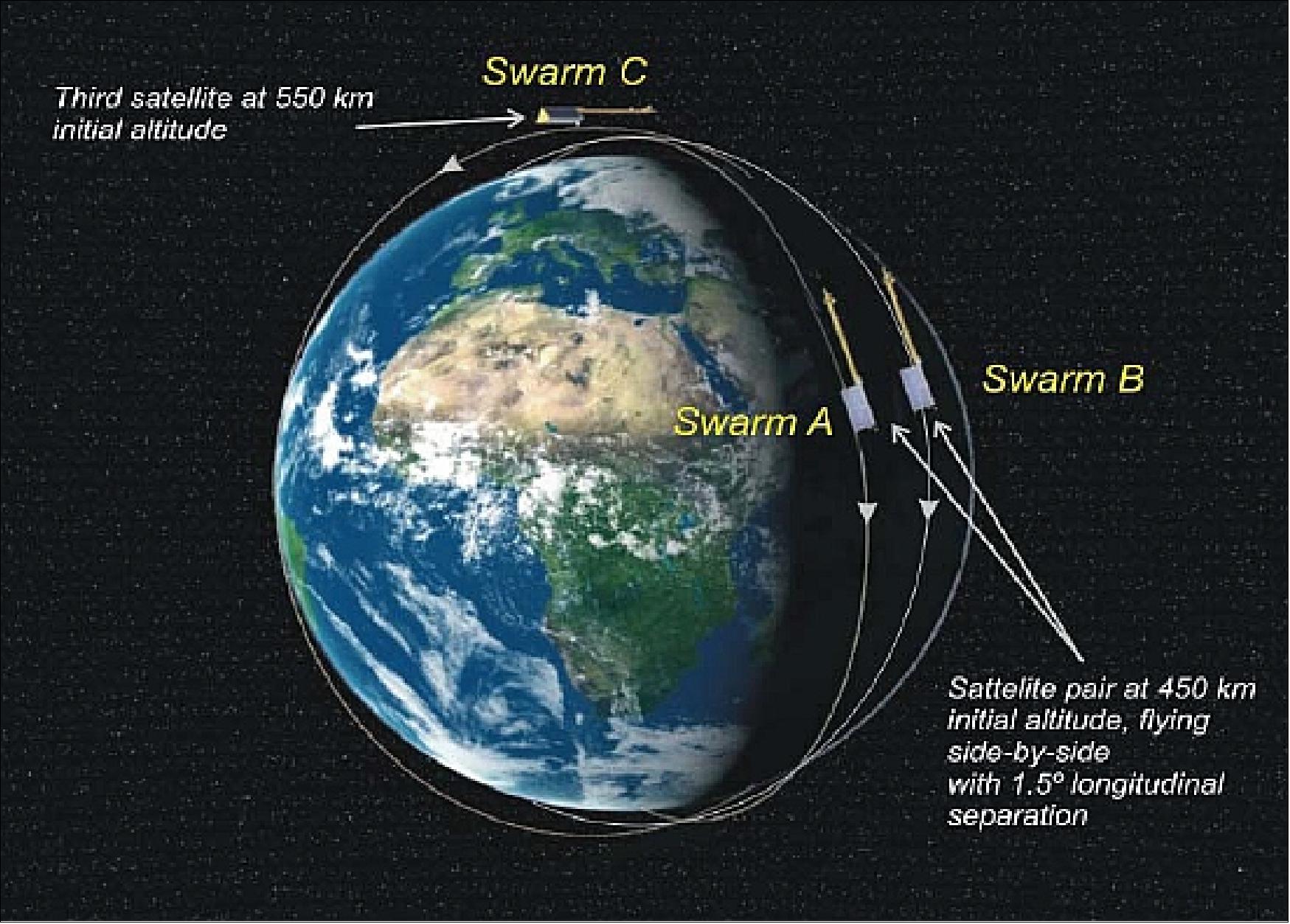

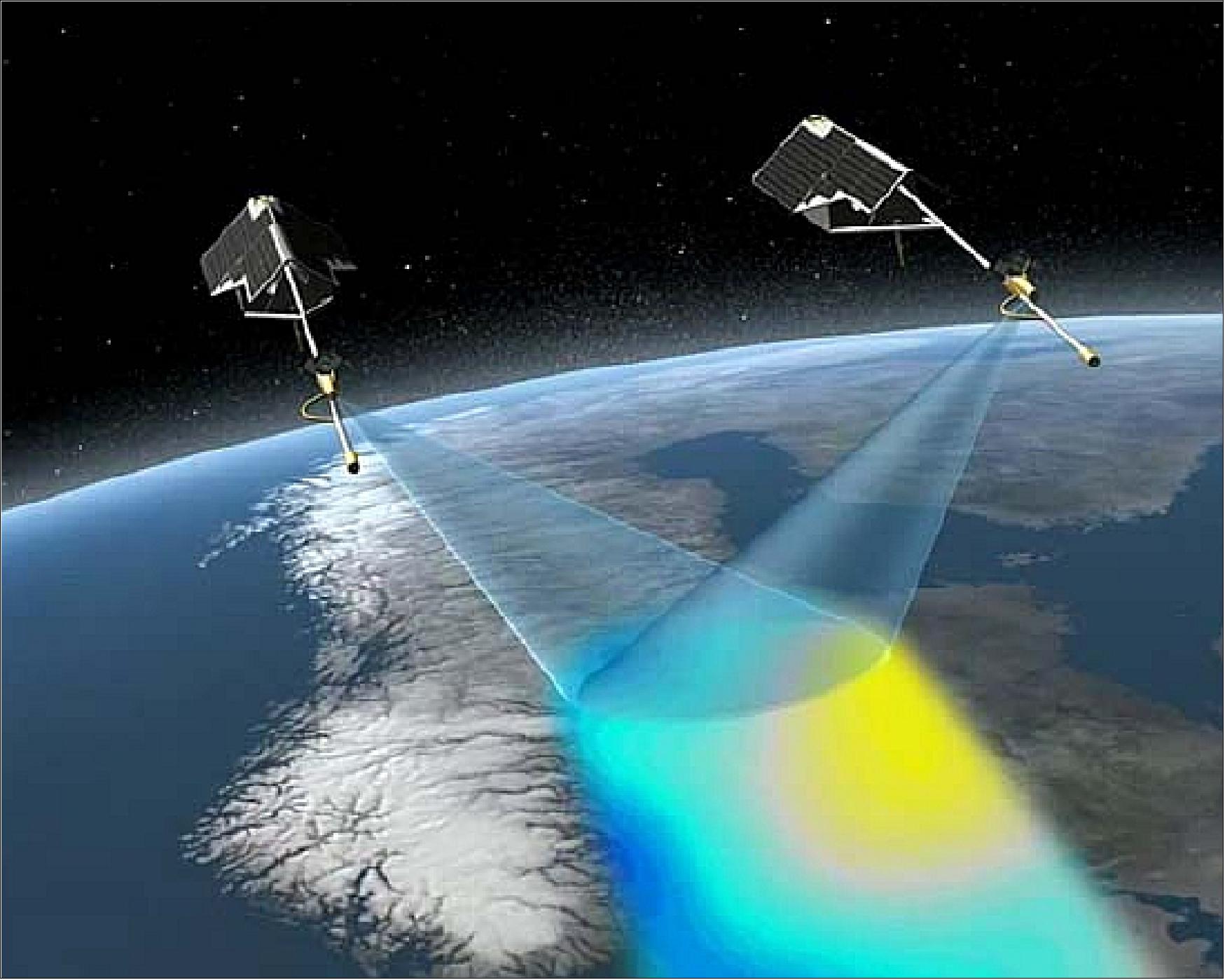

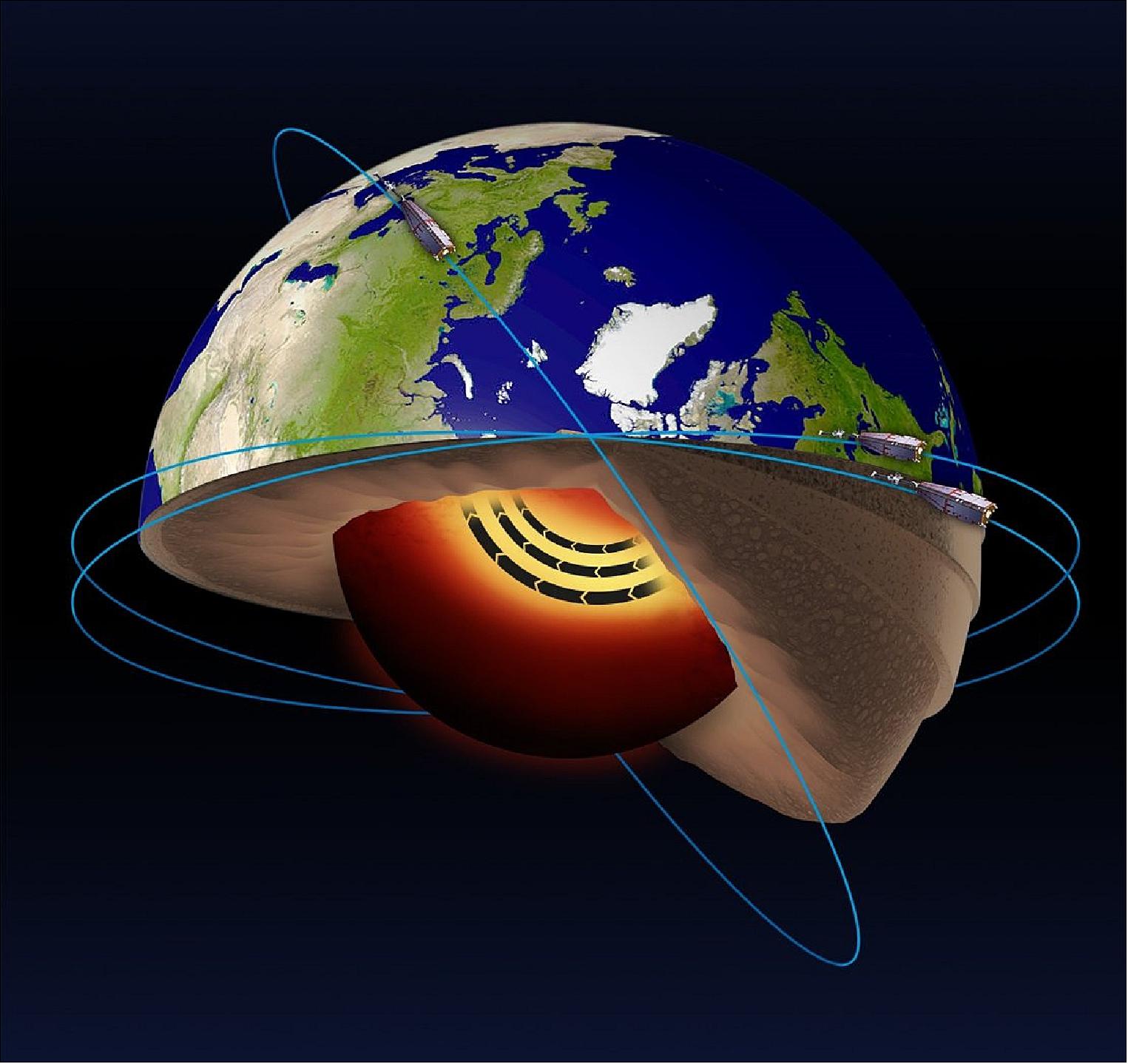

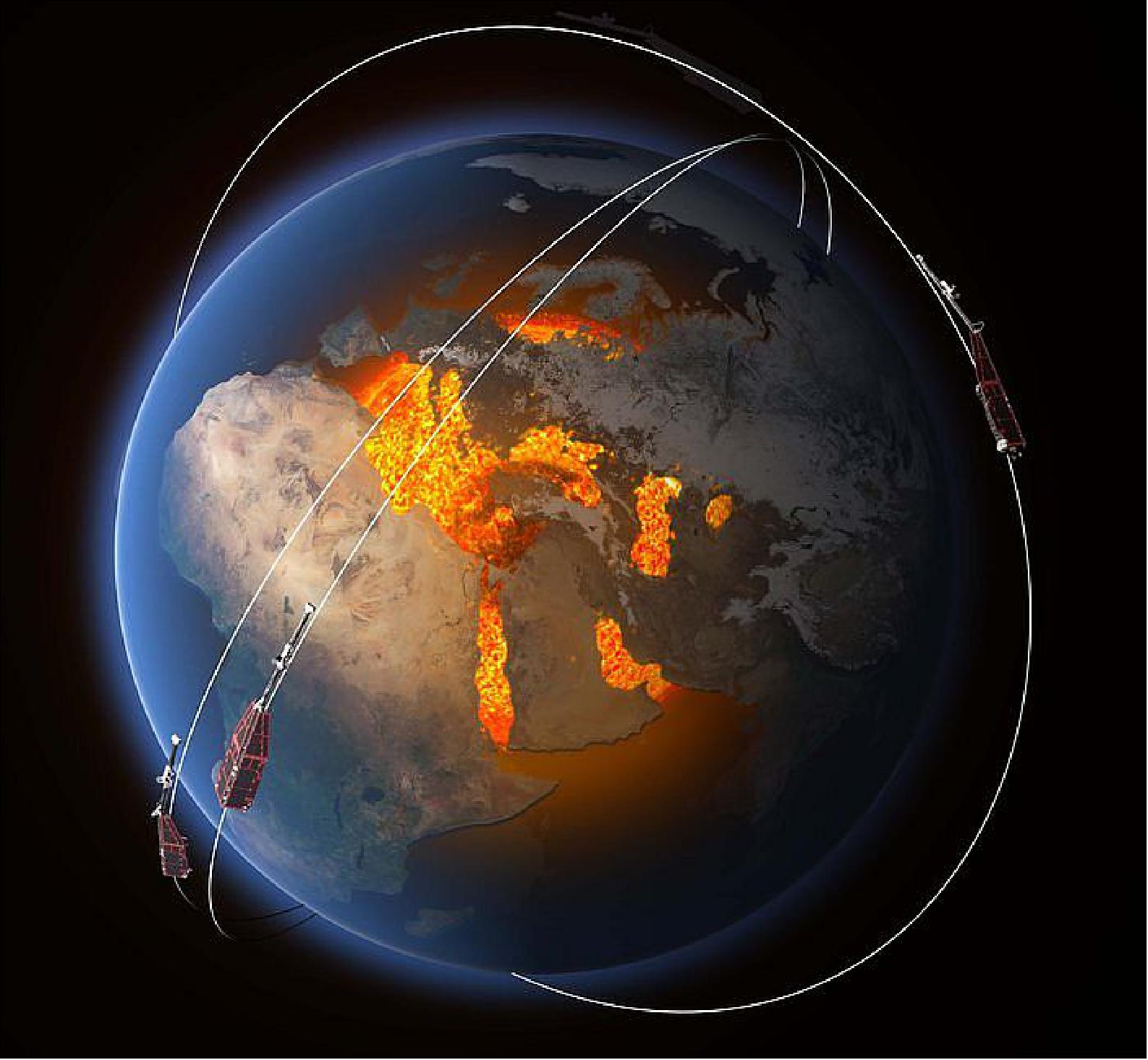

This will be done by a constellation of three satellites, two will fly at a lower altitude, measuring the East-West gradient of the magnetic field, and one satellite will fly at a higher altitude in a different local time sector. Other measurements will also be made to complement the magnetic field measurements. Together these multipoint measurements will allow the deduction of information on a series of solid-Earth processes responsible for the creation of the fields measured.

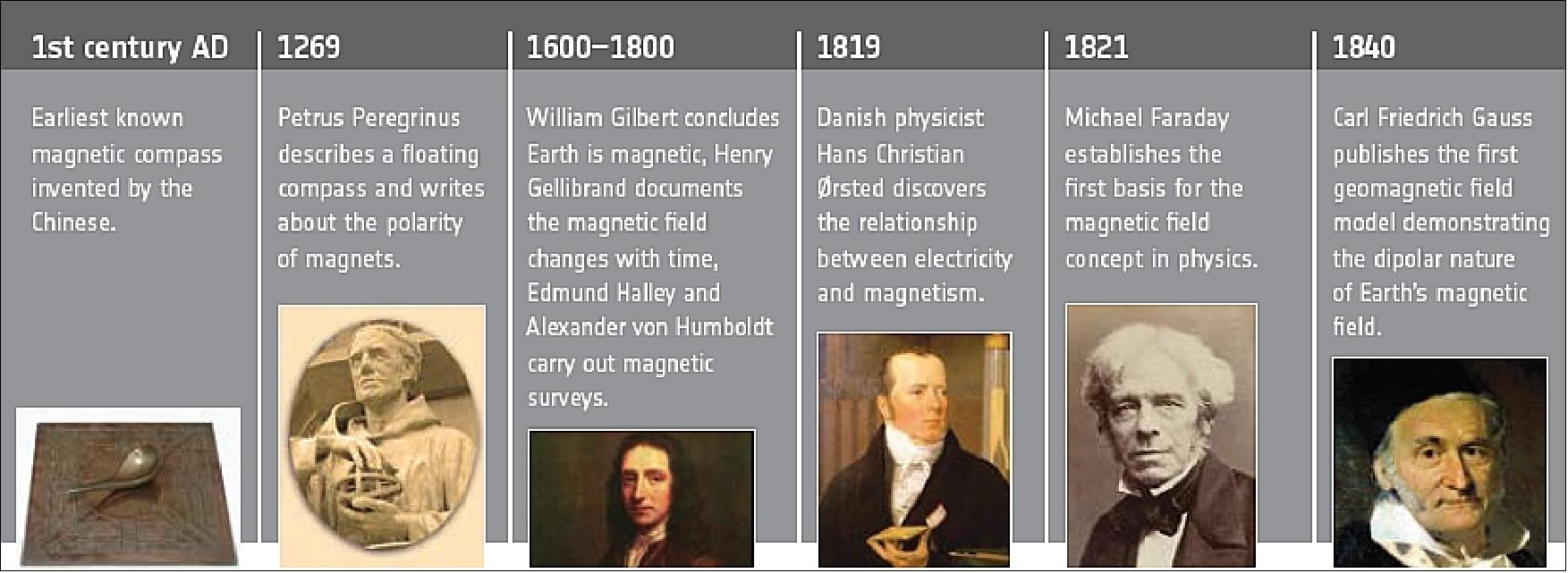

Background on the Discovery of Electromagnetism

The history of magnetic discovery goes back to about 110 B.C., when the earliest magnetic compass was invented by the Chinese. They noticed that if a “lodestone” (natural magnets of iron-rich ore) was suspended so it could turn freely, it would always point in the same direction, toward the magnetic poles. This directional pointing property of magnetic material was eventually introduced into the making of an early compass and used for maritime navigation . By the 13th century, the directive property of magnetism was widely recognized and used in navigation. The mariner’s magnetic compass is the first technological application of magnetism and, one of the oldest scientific instruments.

Until 1820, the only magnetism known was that of iron magnets and of lodestones. It was the Danish physicist Hans Christian Ørsted, professor at the University of Copenhagen, who, in 1820, was first to discover the relationship between the hitherto separate fields of electricity and magnetism. Ørsted showed that a compass needle was deflected when an electric current passed through a wire, before Faraday had formulated the physical law that carries his name: the magnetic field produced is proportional to the intensity of the current. Magnetostatics is the study of static magnetic fields, i.e. fields which do not vary with time. 19) 20)

Magnetic and electric fields together form the two components of electromagnetism. Electromagnetic waves can move freely through space, and also through most materials at pretty much every frequency band (radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visible light, ultraviolet light, X-rays and gamma rays). Electromagnetic fields therefore combine electric and magnetic force fields that may be natural (the Earth's magnetic field) or man-made (low frequencies such as electric power transmission lines and cables, or higher frequencies such as radio waves (including cell phones) or television (Ref. 21).

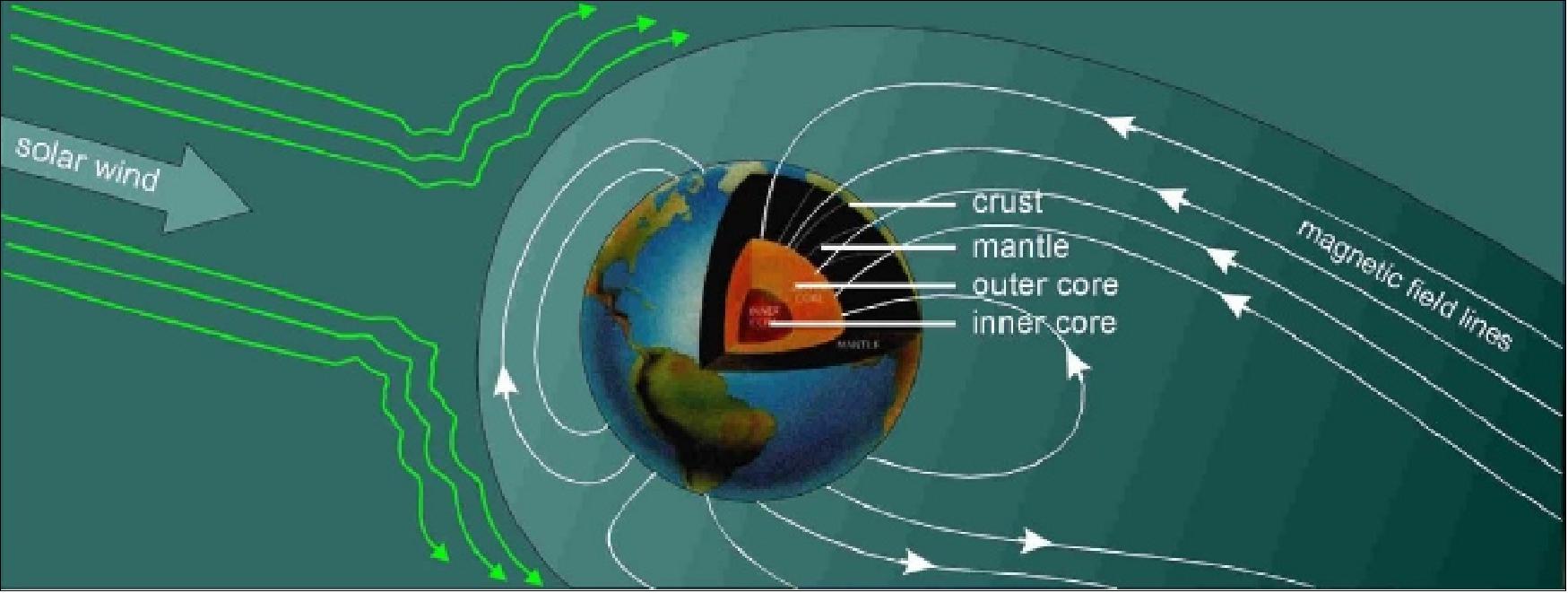

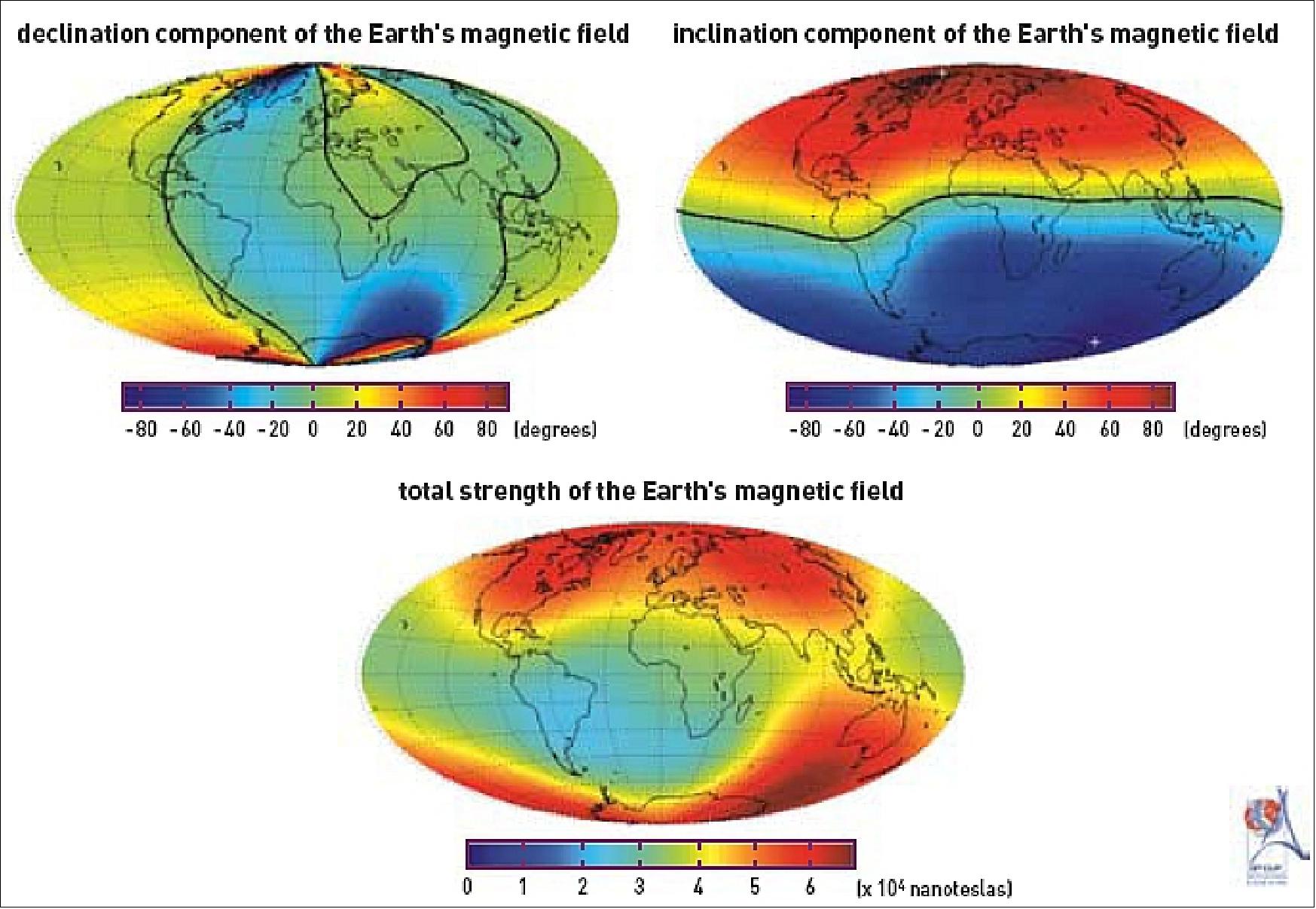

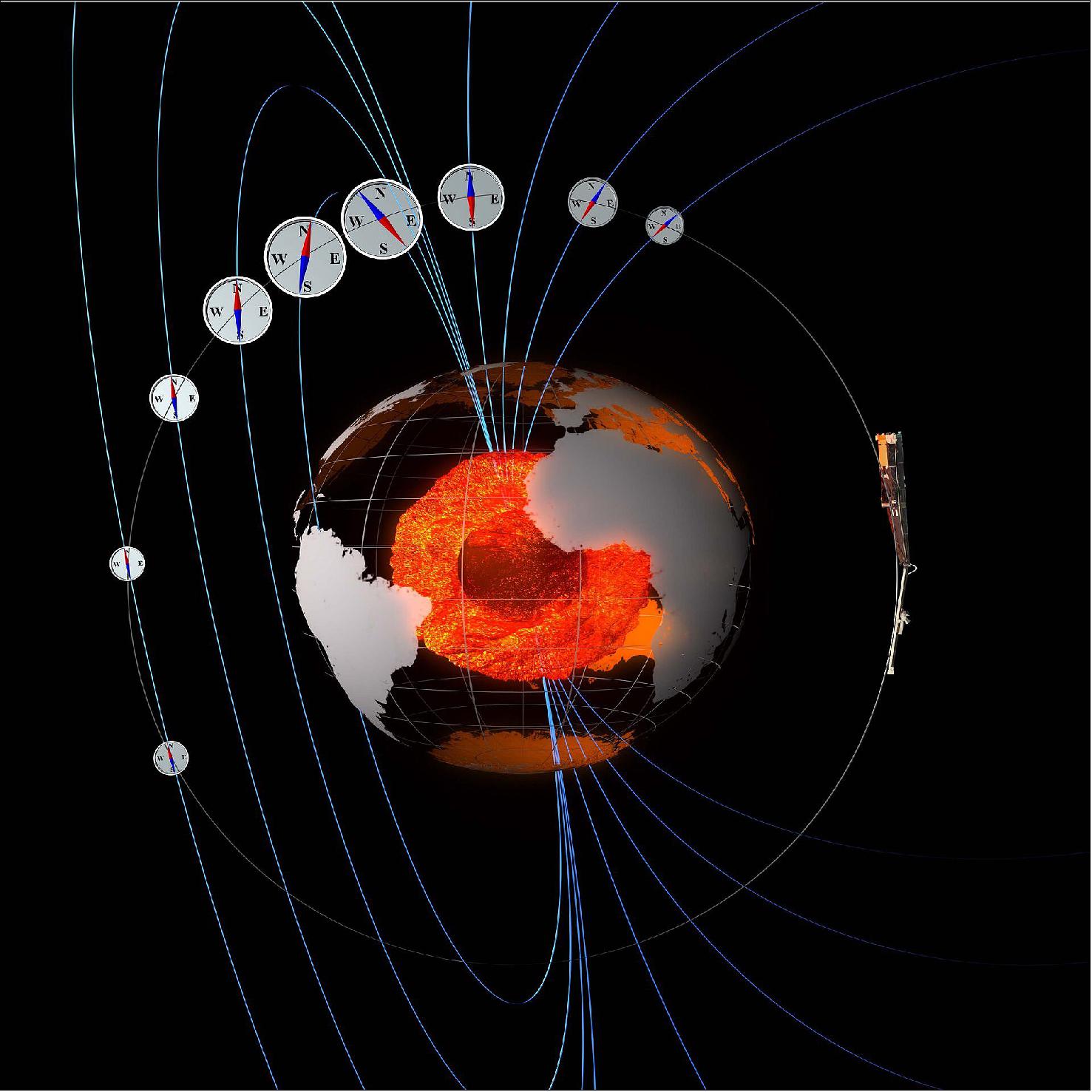

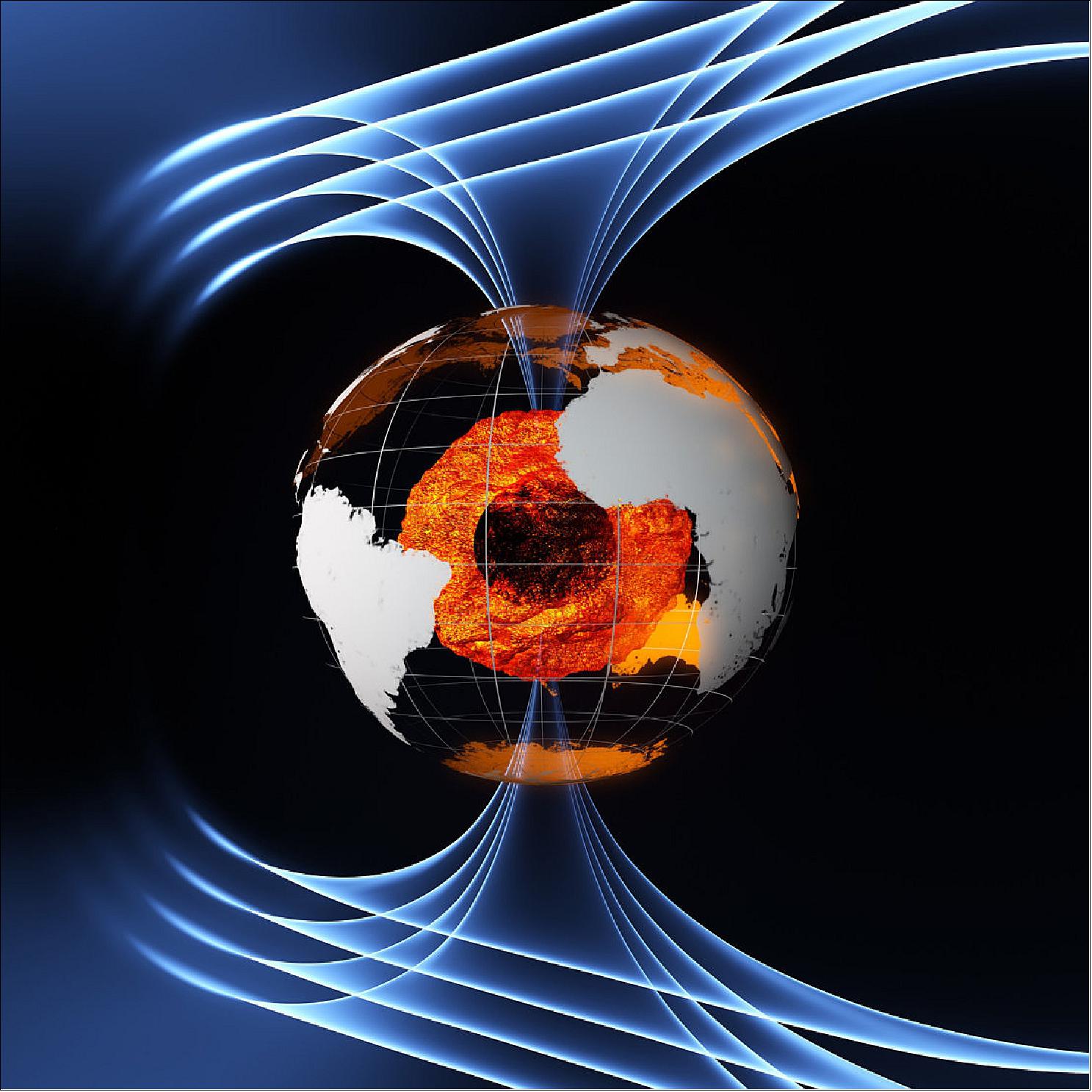

Background on the Earth's Magnetic Field

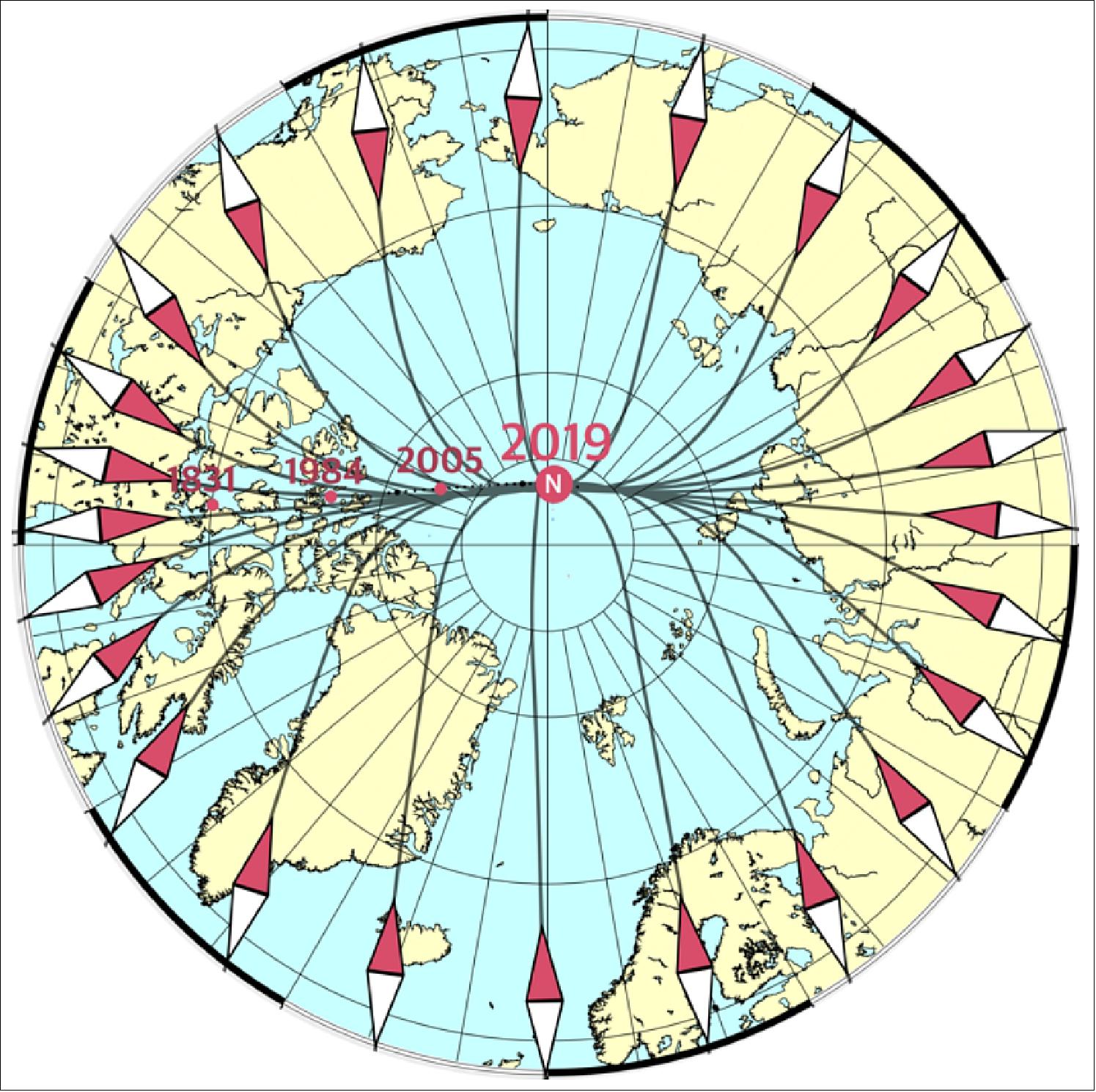

The Earth has its own magnetic field, which acts like a giant magnet. Geomagnetism is the name given to the study of this field, which can be roughly described as a centered dipole whose axis is offset from the Earth's axis of rotation by an angle of about 11.5º. This angle varies over time in response to movements in the Earth's core. The angle between the direction of the magnetic and geographic north poles, called the magnetic declination, varies at different points on the Earth's surface. The angle that the magnetic field vector makes with the horizontal plane at any point on the Earth's surface is called the magnetic inclination.

This centered dipole exhibits magnetic field lines that run between the north and south poles. These field lines convergent and lie vertical to the Earth's surface at two points known as the magnetic poles, which are currently located in Canada and Adélie Land. Compass needles align themselves with the magnetic north pole (which corresponds to the south pole of the 'magnet' at the Earth's core).

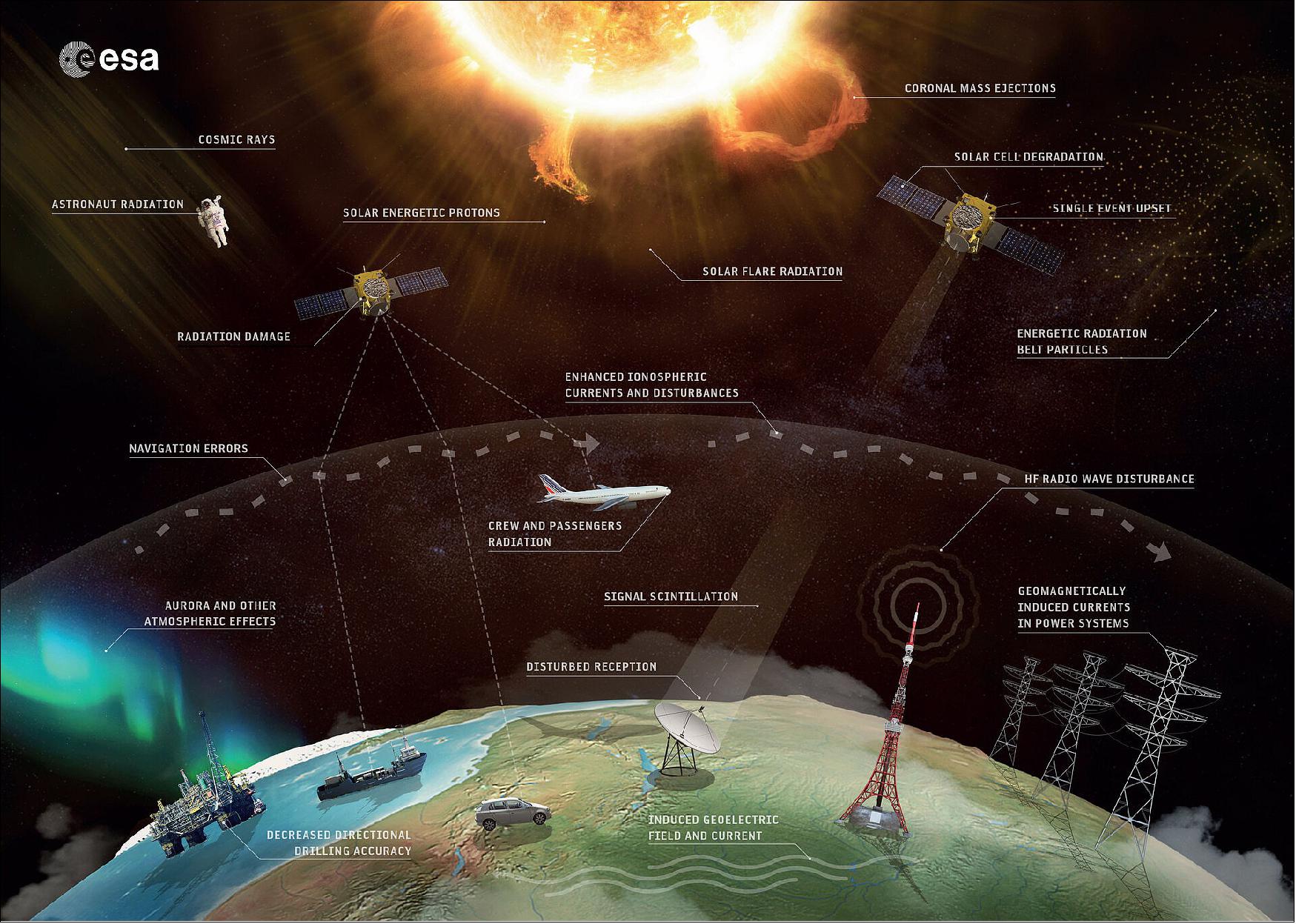

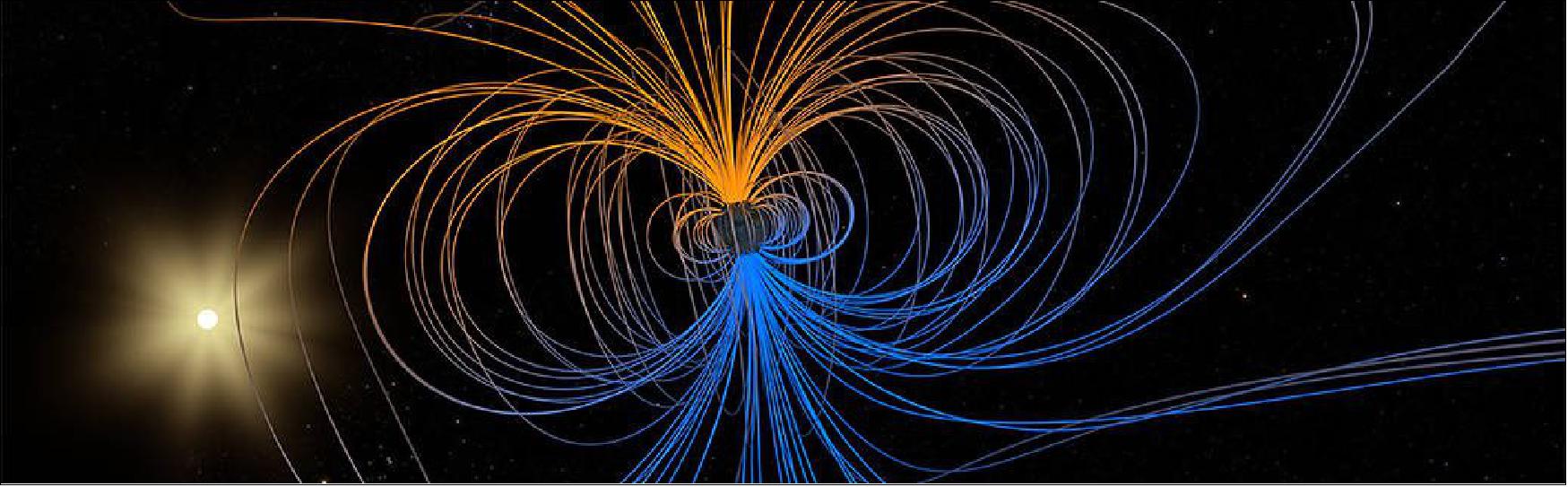

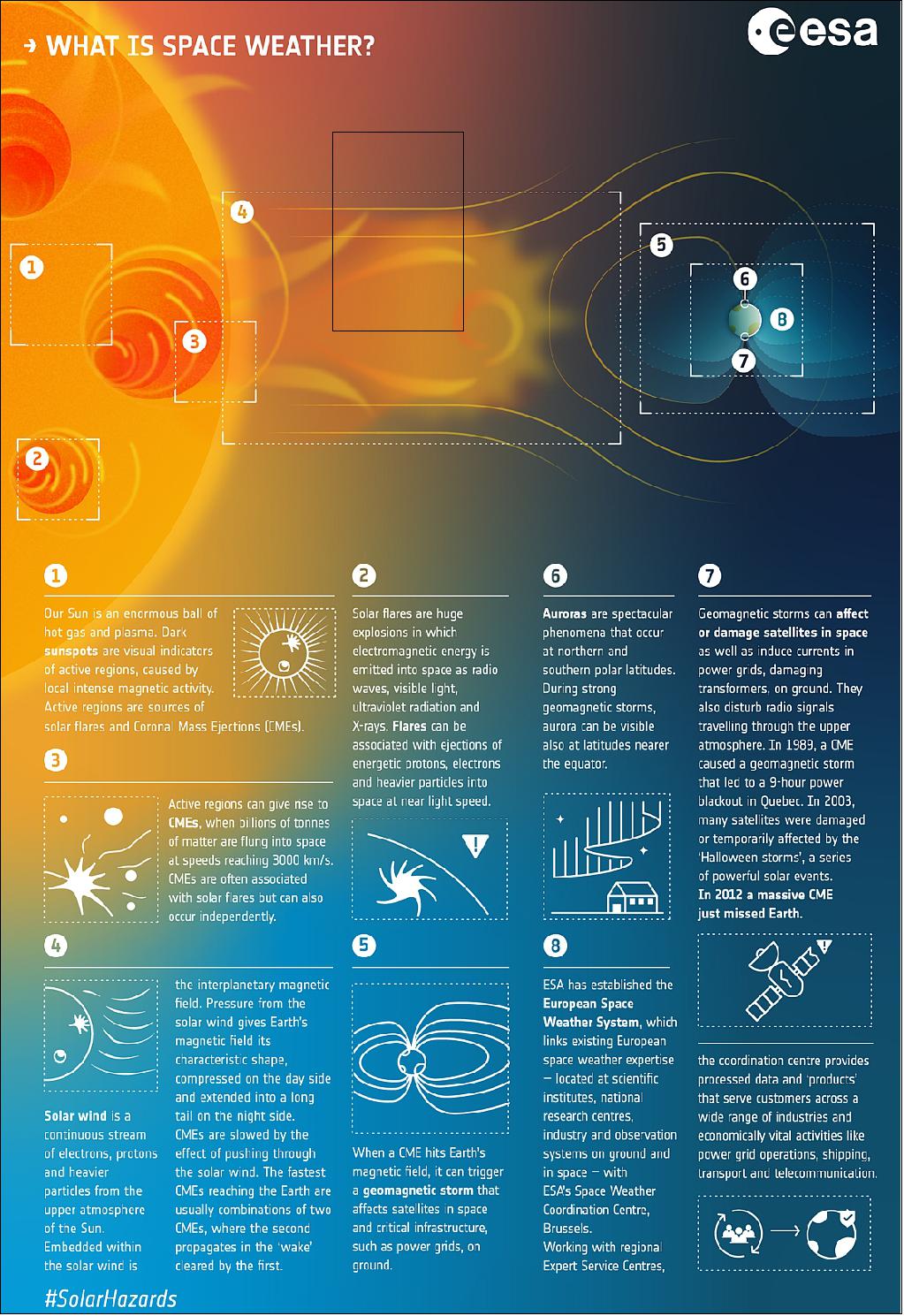

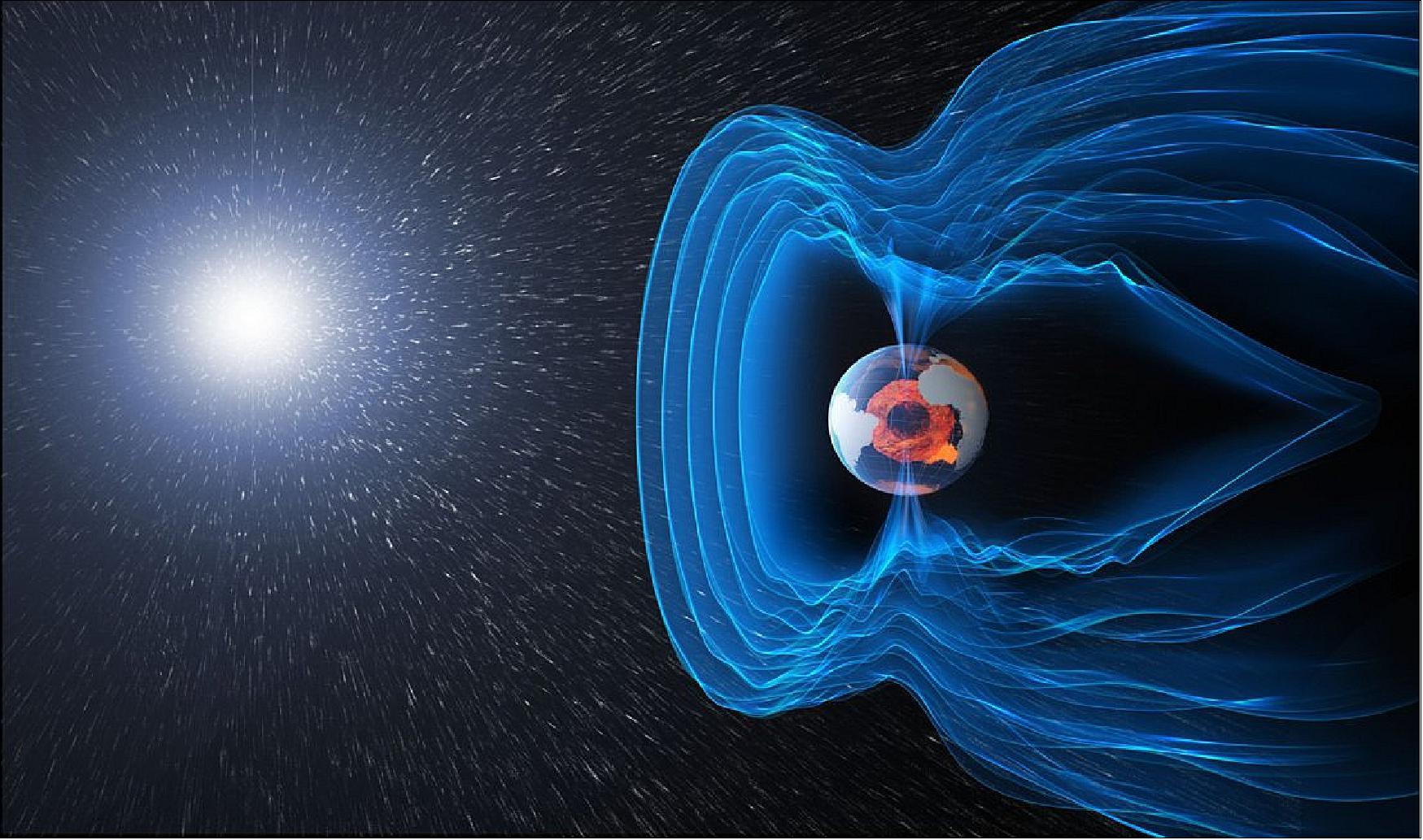

The Earth's magnetic field is a result of the dynamo effect generated by movements in the planet's core, and is fairly weak at around 0.5 gauss, i.e. 5 x 10-5 tesla (this is the value in Paris, for example). The magnetic north pole actually 'wanders' over the surface of the Earth, changing its location by up to tens of km every year. Despite its weakness, the Earth's dipolar field nevertheless screen the Earth from charged particles and protect all life on the planet from the harmful effects of cosmic radiation. In common with other planets in our solar system, the Earth is surrounded by a magnetosphere that shields its surface from solar wind, although this solar wind does manage to distort the Earth's magnetic field lines.

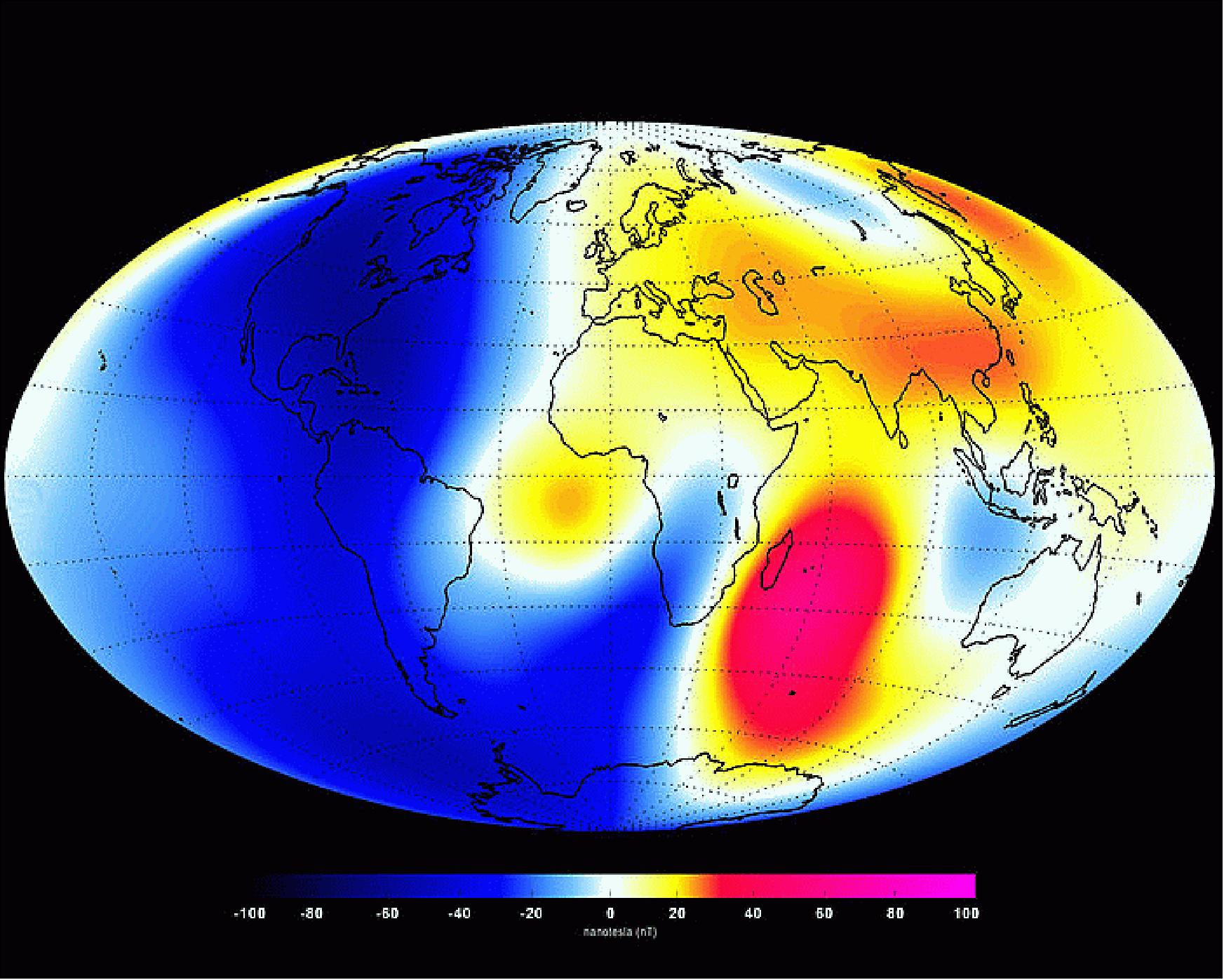

The Earth’s magnetic field shows deviations, called anomalies, from the idealized field of a centered bar magnet. These anomalies can be quite large, affecting areas on a regional scale. One example is the SAA (South Atlantic Anomaly), which affects the amount of cosmic radiation reaching the passengers and crew of any plane and spacecraft led to cross it (Ref. 21).

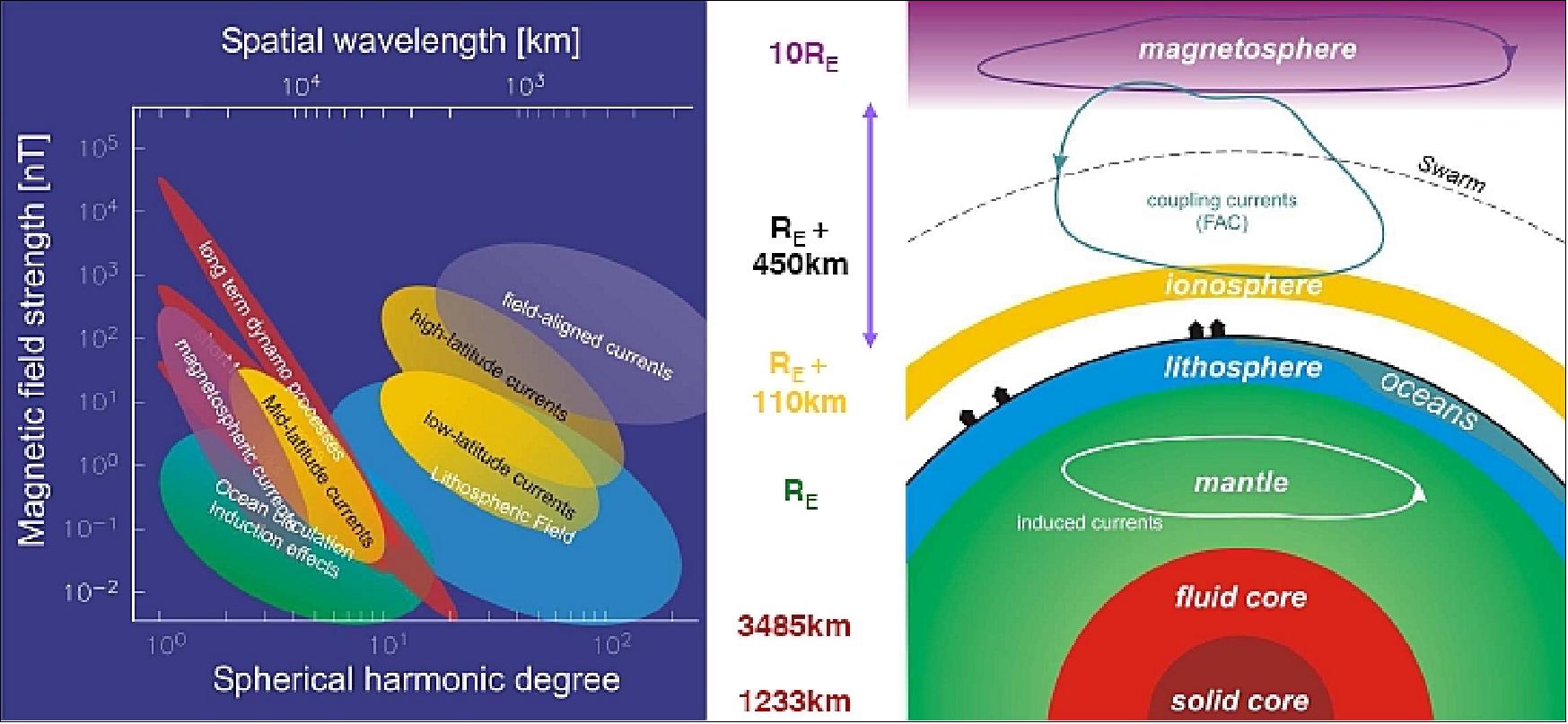

The primary research topics to be addressed by the Swarm mission include: 23)

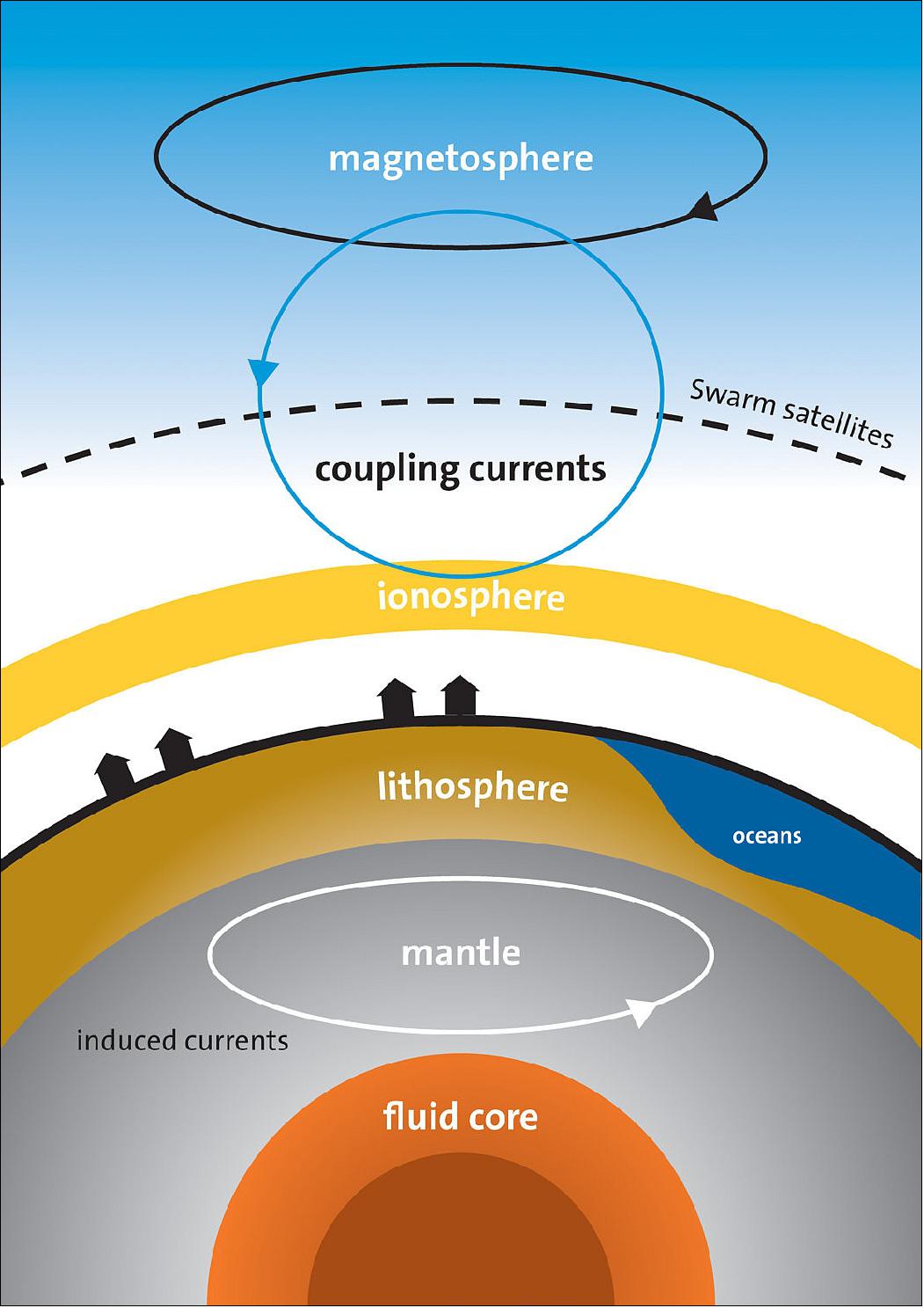

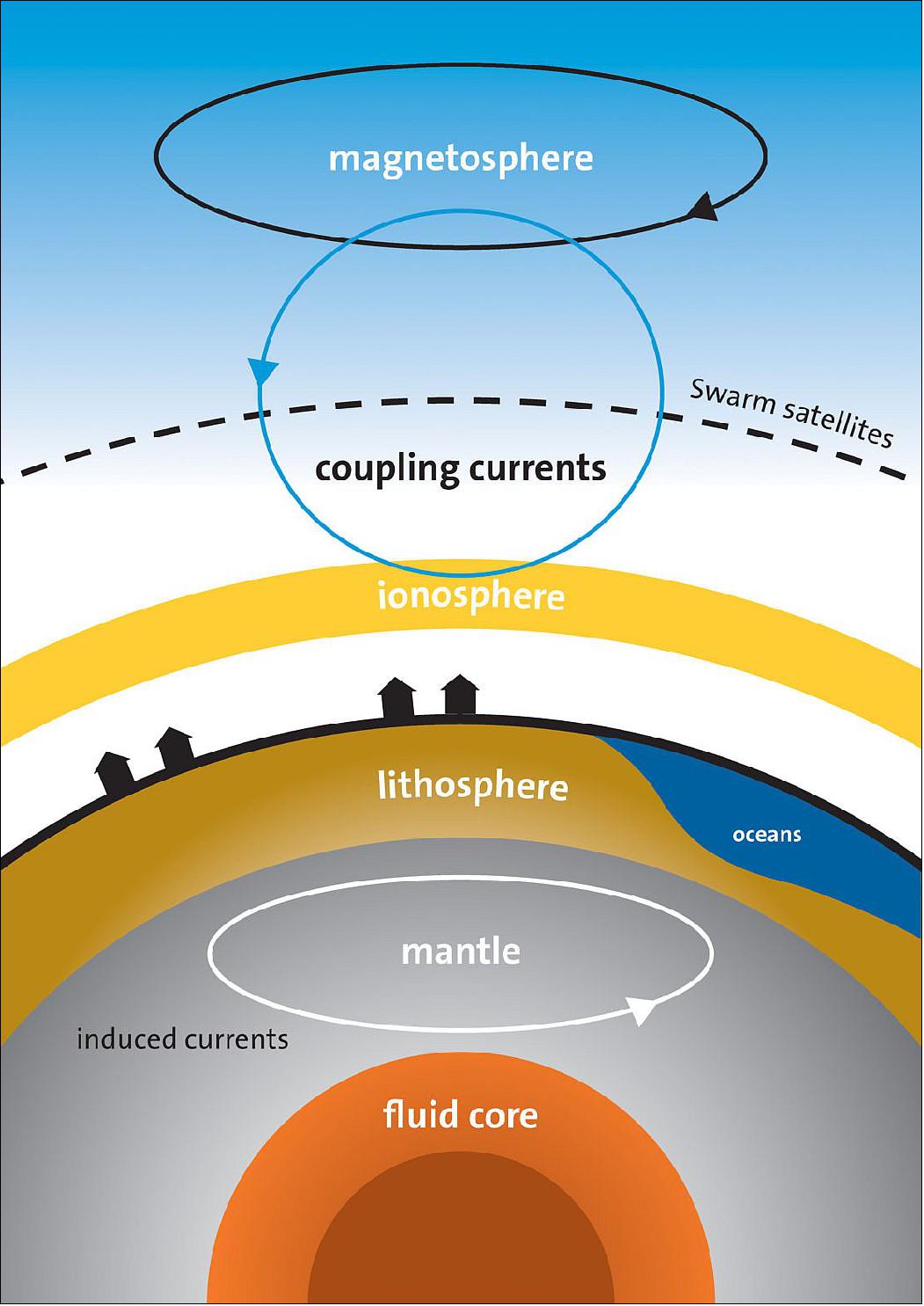

• Core dynamics, geodynamo processes, and coremantle interaction. - The goal is to improve the models of the core field dynamics by ensuring long-term space observations with an even better spatial and temporal resolution. Combining existing Ørsted, CHAMP and future Swarm observations will also more generally allow the investigation of all magnetohydrodynamic phenomena potentially affecting the core on sub-annual to decadal scales, down to wavelengths of about 2000 km. Of particular interest are those phenomena responsible for field changes that cannot be accounted for by core surface flow models. 24)

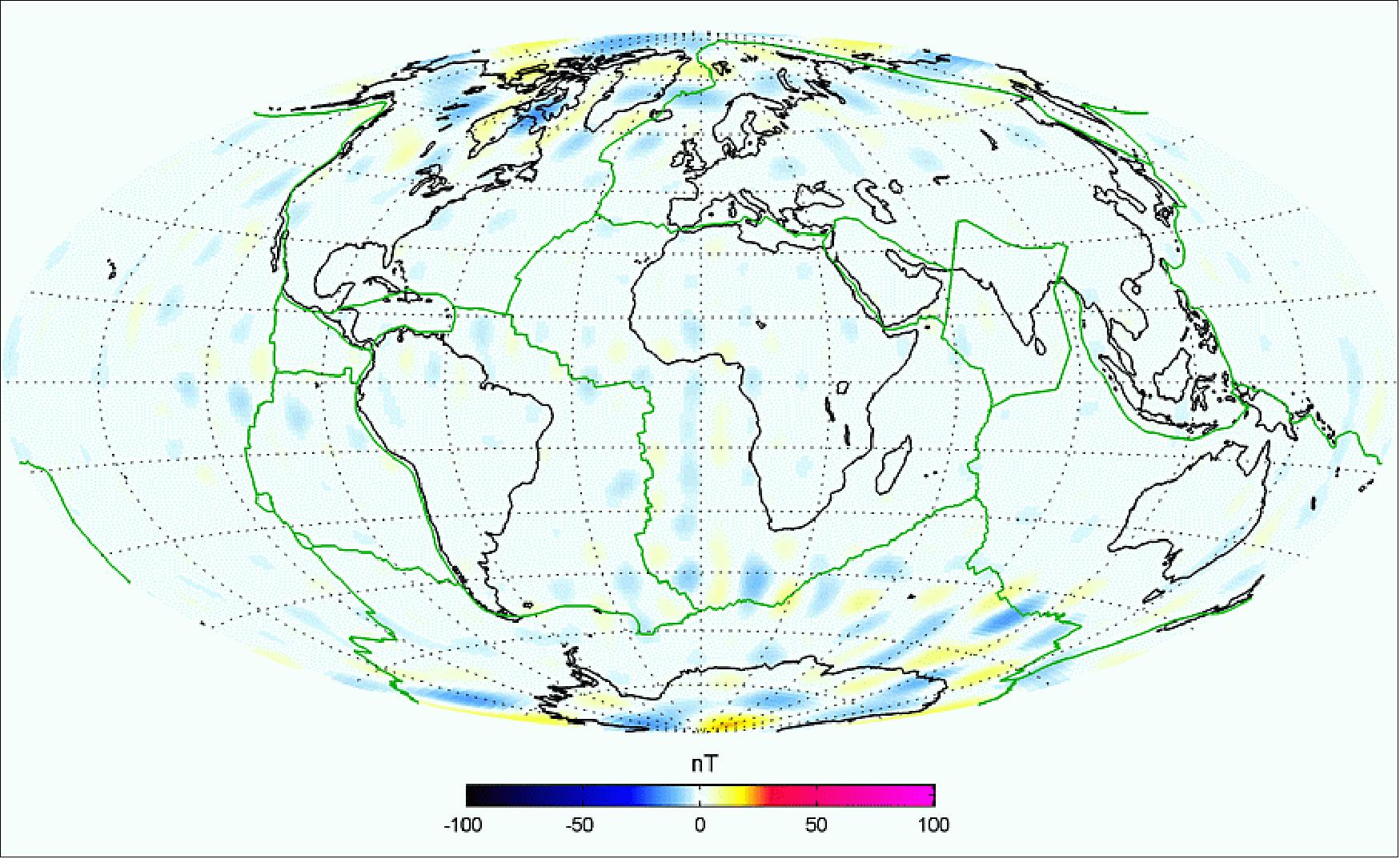

• Lithospheric magnetization and its geological interpretation. - The increased resolution of the Swarm satellite constellation will allow, for the first time, the identification from satellite altitude of the oceanic magnetic stripes corresponding to periods of reversing magnetic polarity. Such a global mapping is important because the sparse data coverage in the southern oceans has been a severe limitation regarding our understanding of plate tectonics in the oceanic lithosphere. Another important implication of improved resolution of the lithospheric magnetic field is the possibility to derive global maps of heat flux. 25) 26)

• 3-D electrical conductivity of the mantle. - Our knowledge of the physical and chemical properties of the mantle can be significantly improved if we know its electrical conductivity. Due to the sparse and inhomogeneous distribution of geomagnetic observatories, with only few in oceanic regions, a true global picture of mantle conductivity can only be obtained from space.

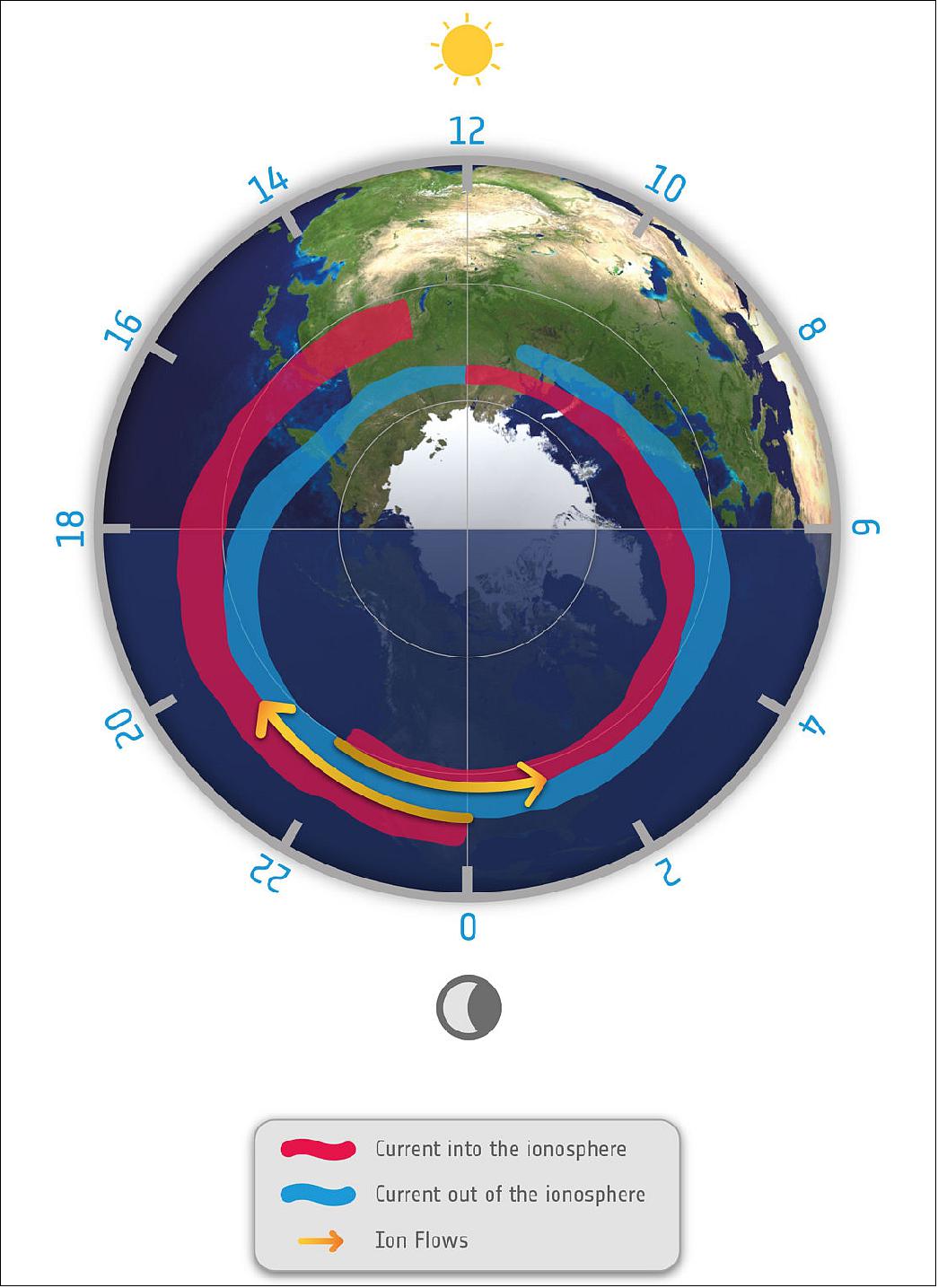

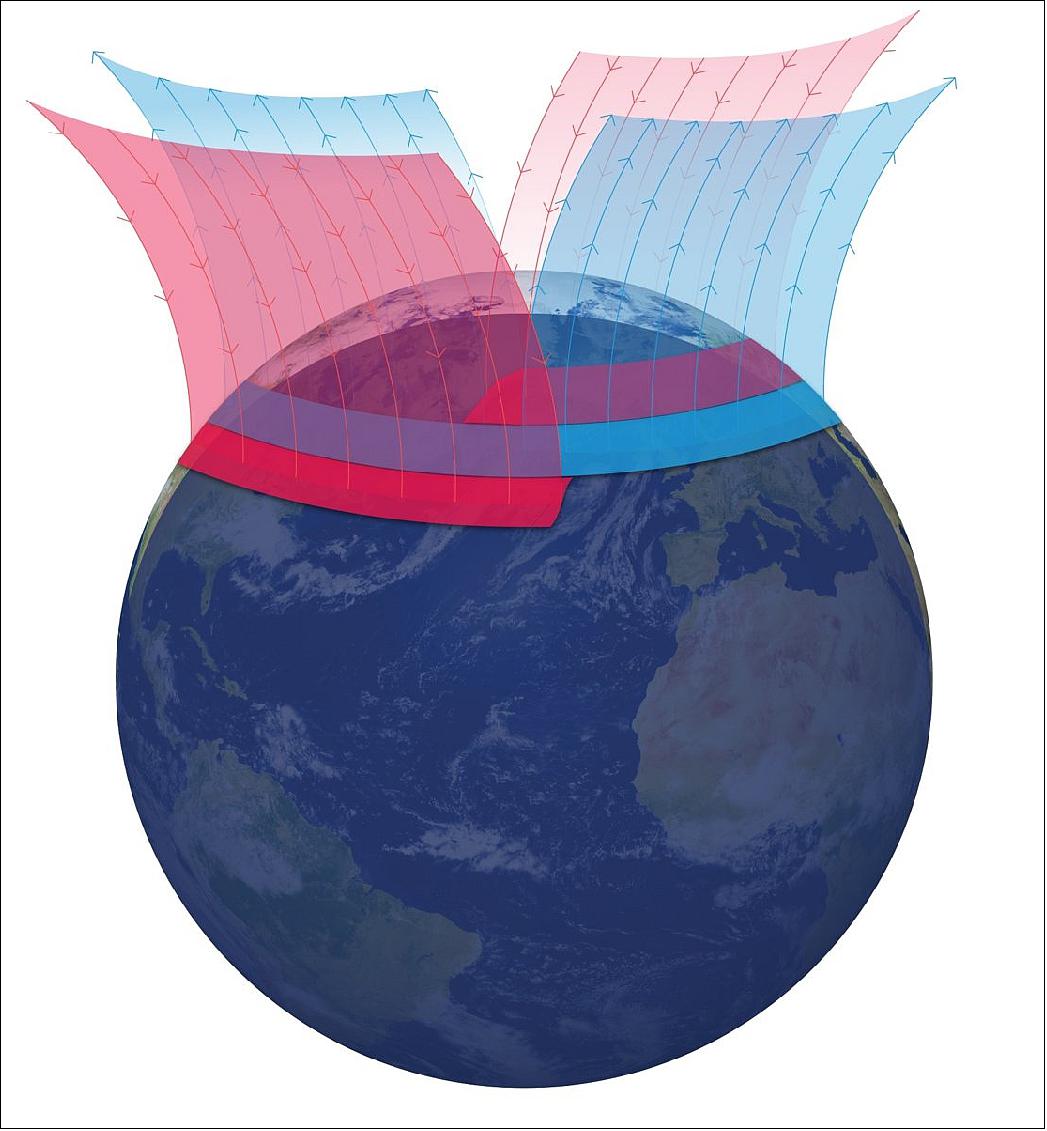

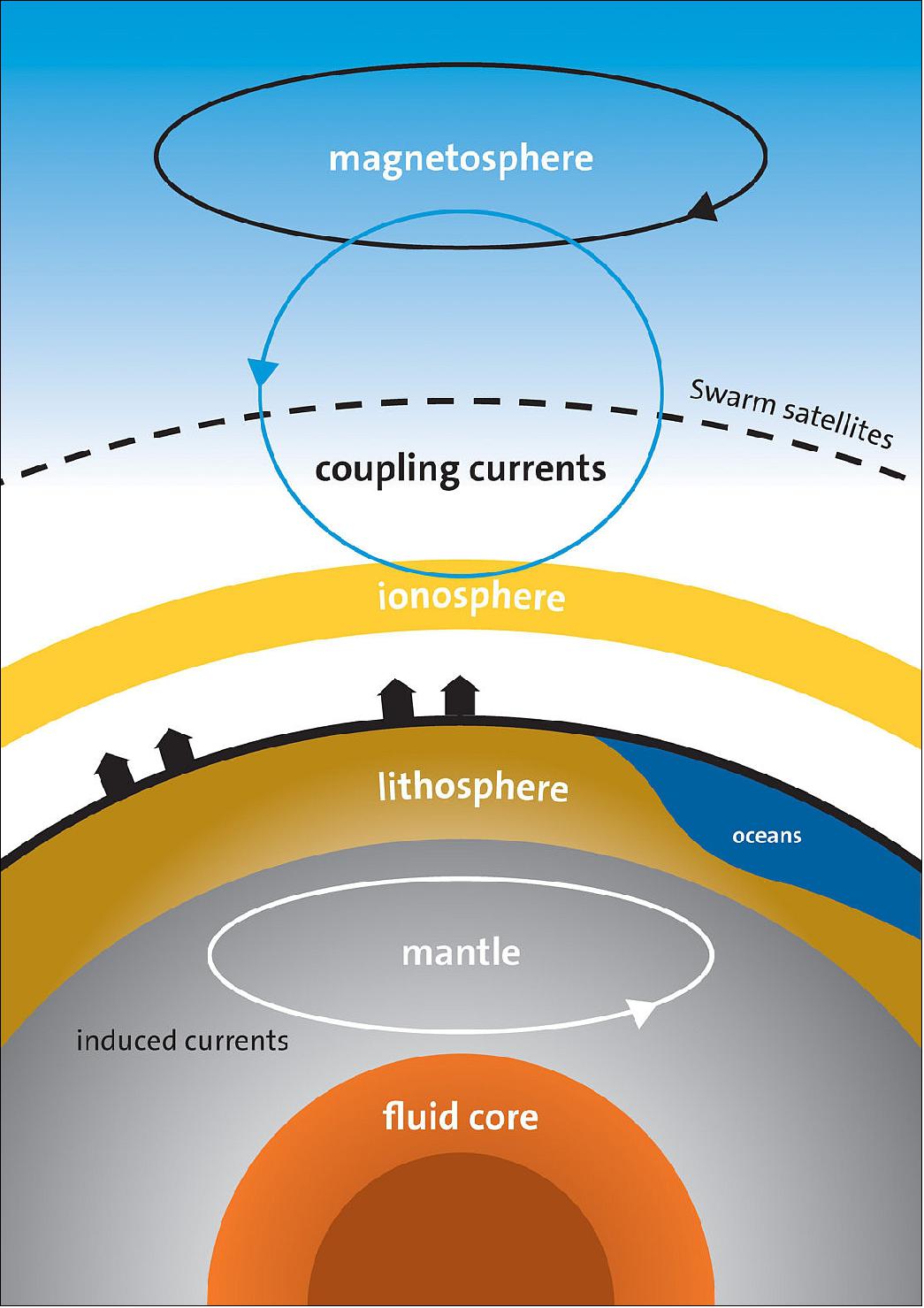

• Currents flowing in the magnetosphere and ionosphere. - Simultaneous measurements at different altitudes and local times, as foreseen with the Swarm mission, will allow better separation of internal and external sources, thereby improving geomagnetic field models. In addition to the benefit of internal field research, a better description of the external magnetic field contributions is of direct interest to the science community, in particular for space weather research and applications. The local time distribution of simultaneous data will foster the development of new methods of co-estimating the internal and external contributions.

The Secondary Research Objectives Include...

• Identification of the ocean circulation by its magnetic signature. - Moving sea-water produces a magnetic field, the signature of which contributes to the magnetic field at satellite altitude. Based on state-of-the-art ocean circulation and conductivity models it has been demonstrated that the expected field amplitudes are well within the resolution of the Swarm satellites. 27)

• Quantification of the magnetic forcing of the upper atmosphere. - The geomagnetic field exerts a direct control on the dynamics of the ionized and neutral particles in the upper atmosphere, which may even have some influence on the lower atmosphere. With the dedicated set of instruments, each of the Swarm satellites will be able to acquire high-resolution and simultaneous in-situ measurements of the interacting fields and particles, which are the key to understanding the system.

Historic background of Swarm: Ref. 13)

• The first Swarm proposal was made in 1998, prior to launch of the Ørsted mission.

• In early 2002, the Swarm mission was proposed to ESA by Eigil Friis-Christensen of DNSC (Copenhagen, Denmark), Hermann Lühr of GFZ (GeoForschungszentrum, Potsdam, Germany), and Gauthier Hulot of IPG (Institut de Physique du Globe, Paris, France) with support from scientists in seven European countries and the USA. In the meantime, the Swarm team comprises participation of 27 institutes on a global scale. The mission was selected for feasibility studies in 2002. The initial mission proposal considered a Swarm constellation of 4 spacecraft. 28)

• In May 2002 there were three mission candidates: ACE+, EGPM and Swarm; they were chosen for a feasibility study.

• At the end of two parallel feasibility studies, the Swarm mission was selected as the 5th mission in ESA's Earth Explorer Program in May 2004. Phase A was completed in Nov. 2005, resulting in a constellation of 3 spacecraft.

• New Concept – Constellation to characterize external sources:

- The external contributions are highly influenced by solar activity and local time

- Simultaneous satellites in different orbital planes are necessary in order to overcome the time-space ambiguity in the measurements. The optimum constellation depends on the scientific objectives.

- But, measurements of high accuracy are not sufficient! A better understanding of the various sources is equally important, in particular when doing measurements with unprecedented precision, where new phenomena appear in the data. For this, additional and independent key information is needed: a) electric field, b) ionospheric conductivity.

• In 2006, the Swarm project was in Phase B, ending with the PDR (Preliminary Design Review) in the summer 2007.

The construction of the Swarm constellation commenced in November 2007 with the Phase C/D kick-off meeting. The Swarm project CDR (Critical Design Review) took place on Oct. 14, 2008 at ESA/ESTEC. 29)

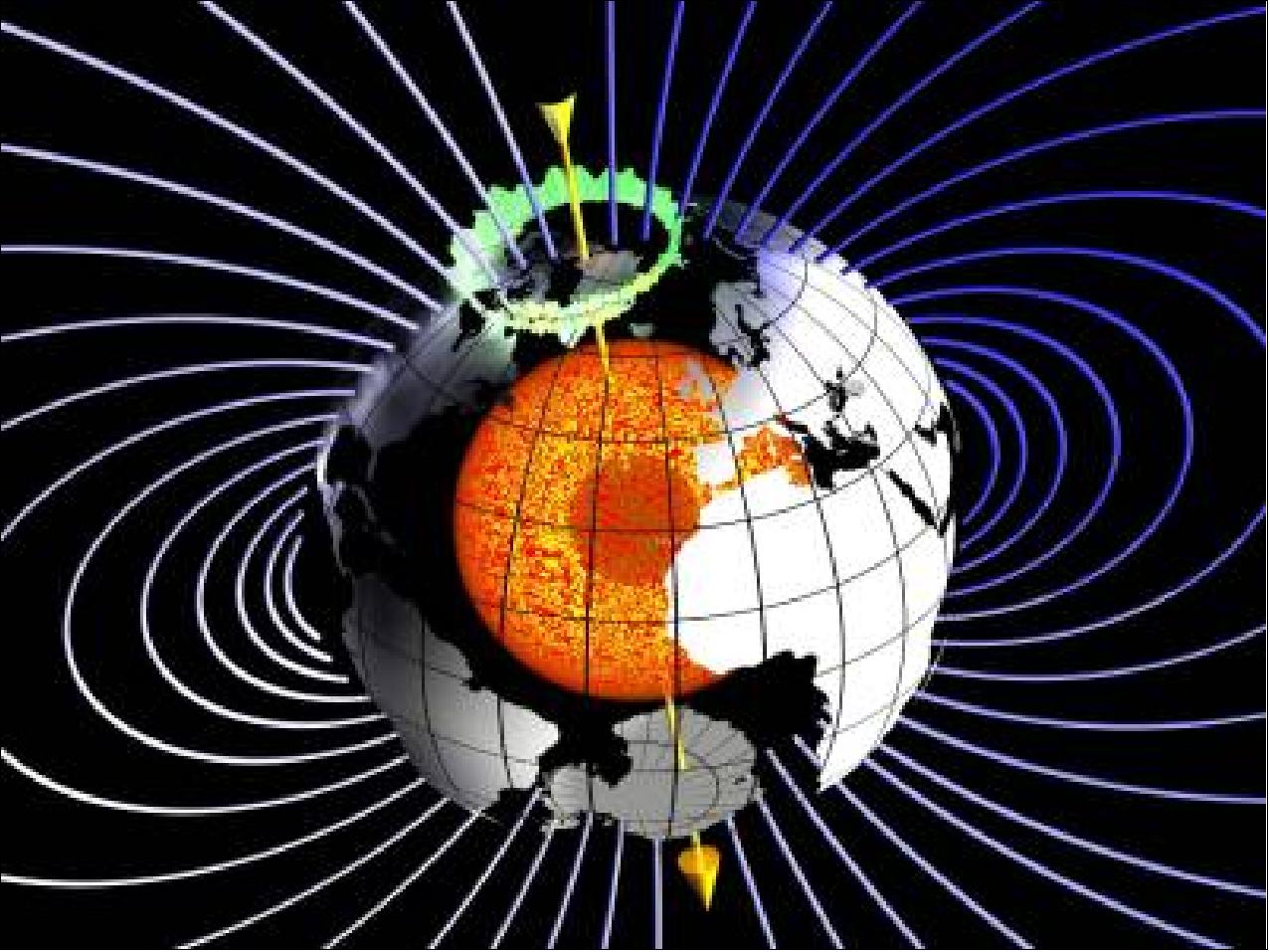

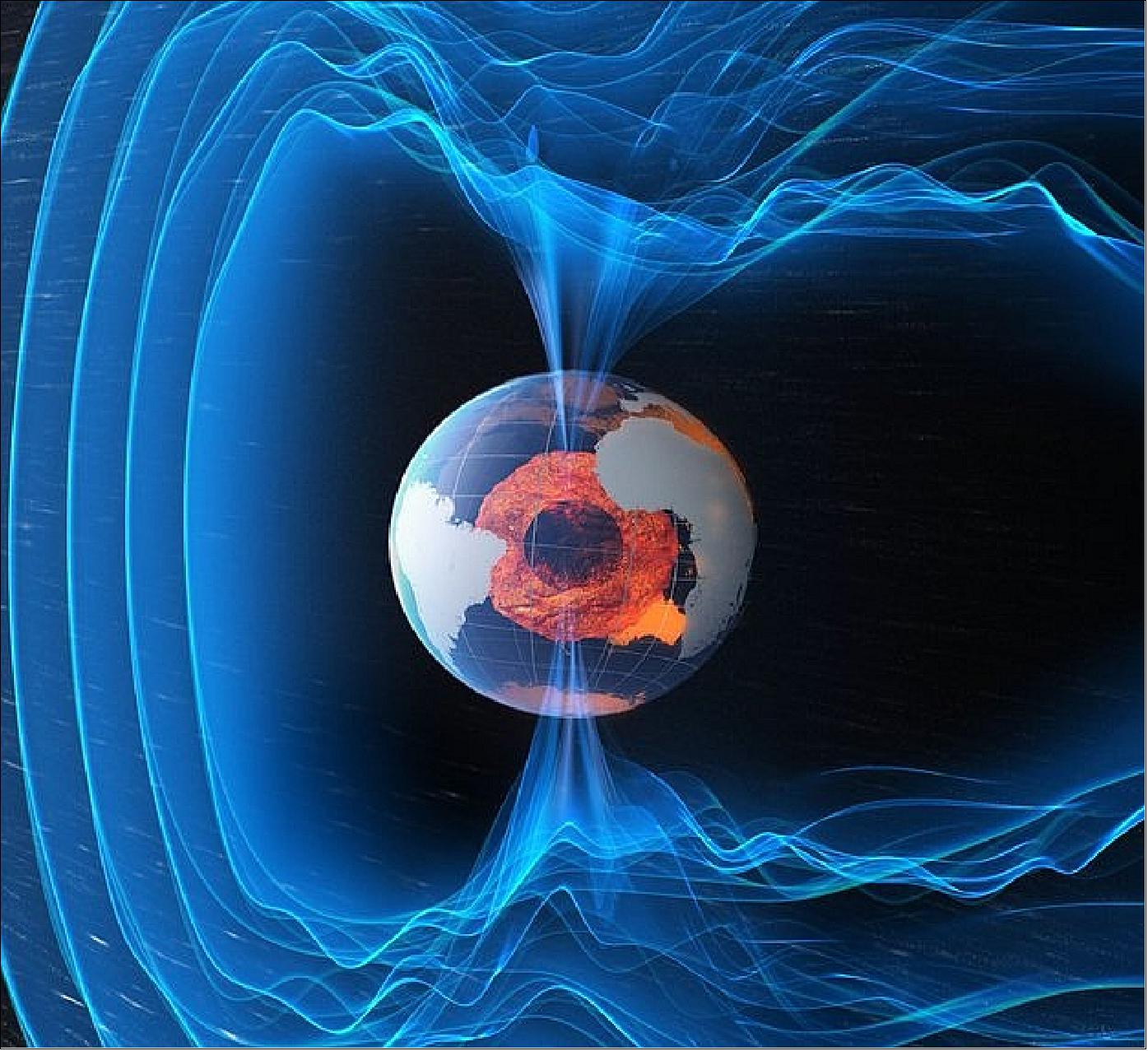

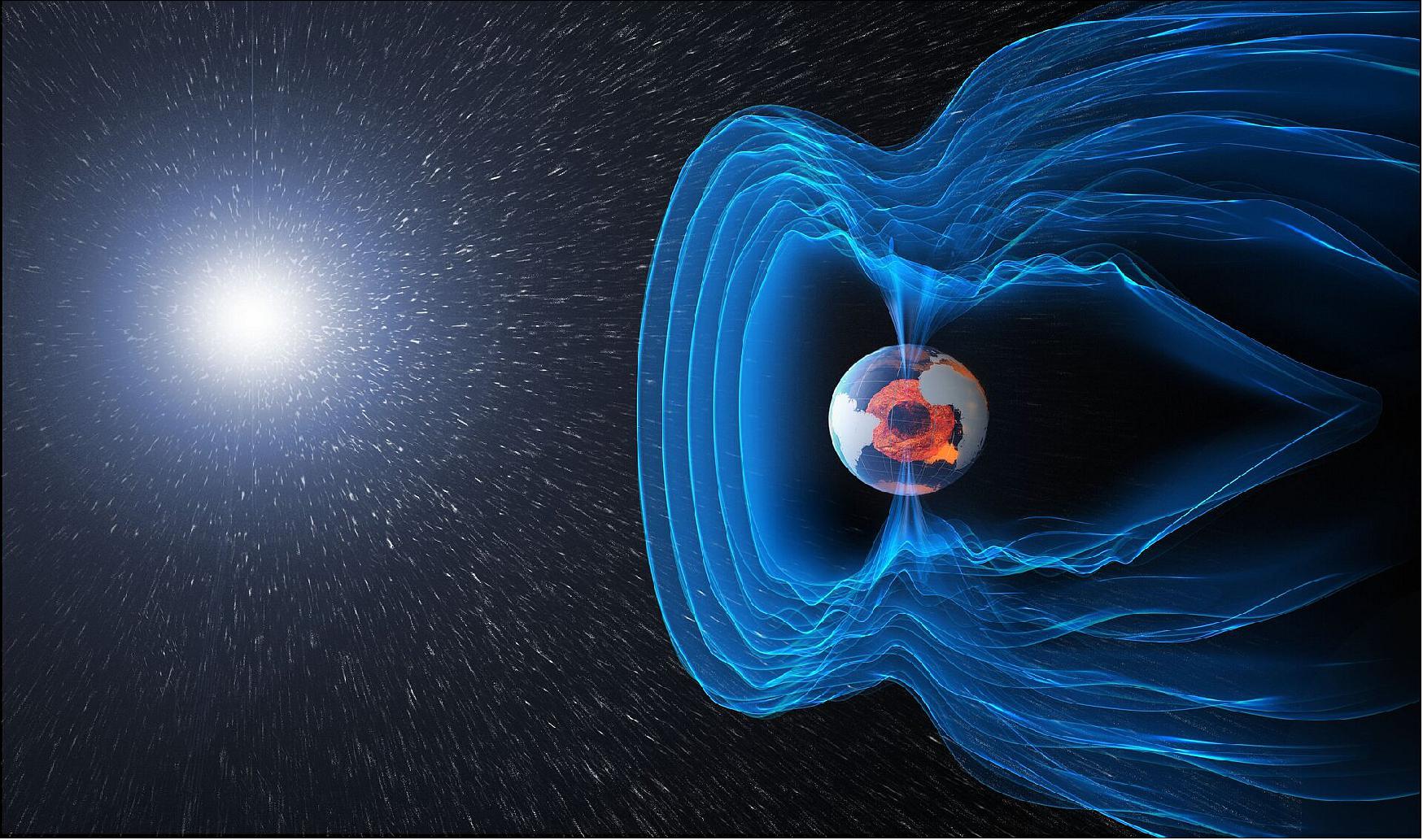

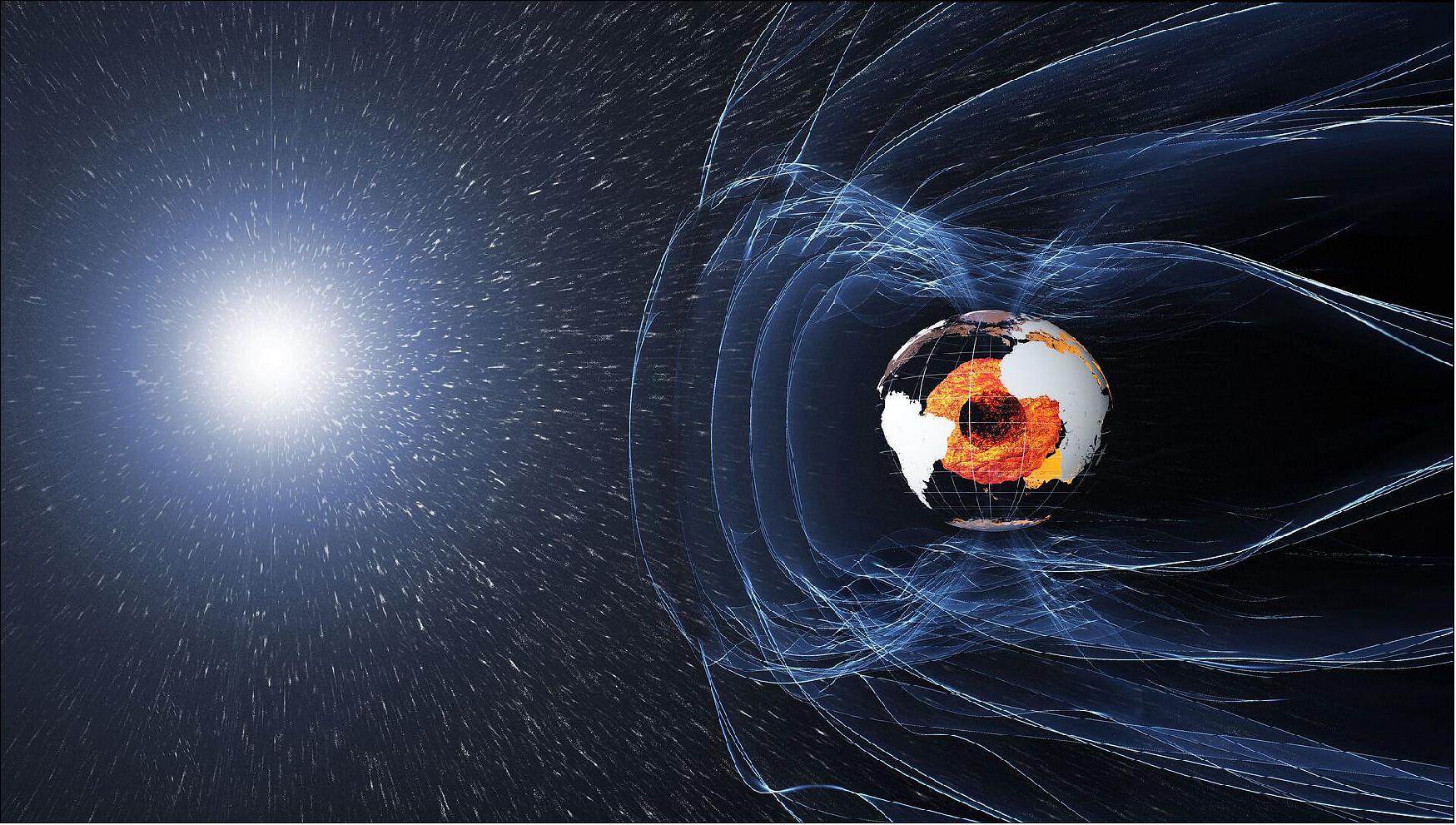

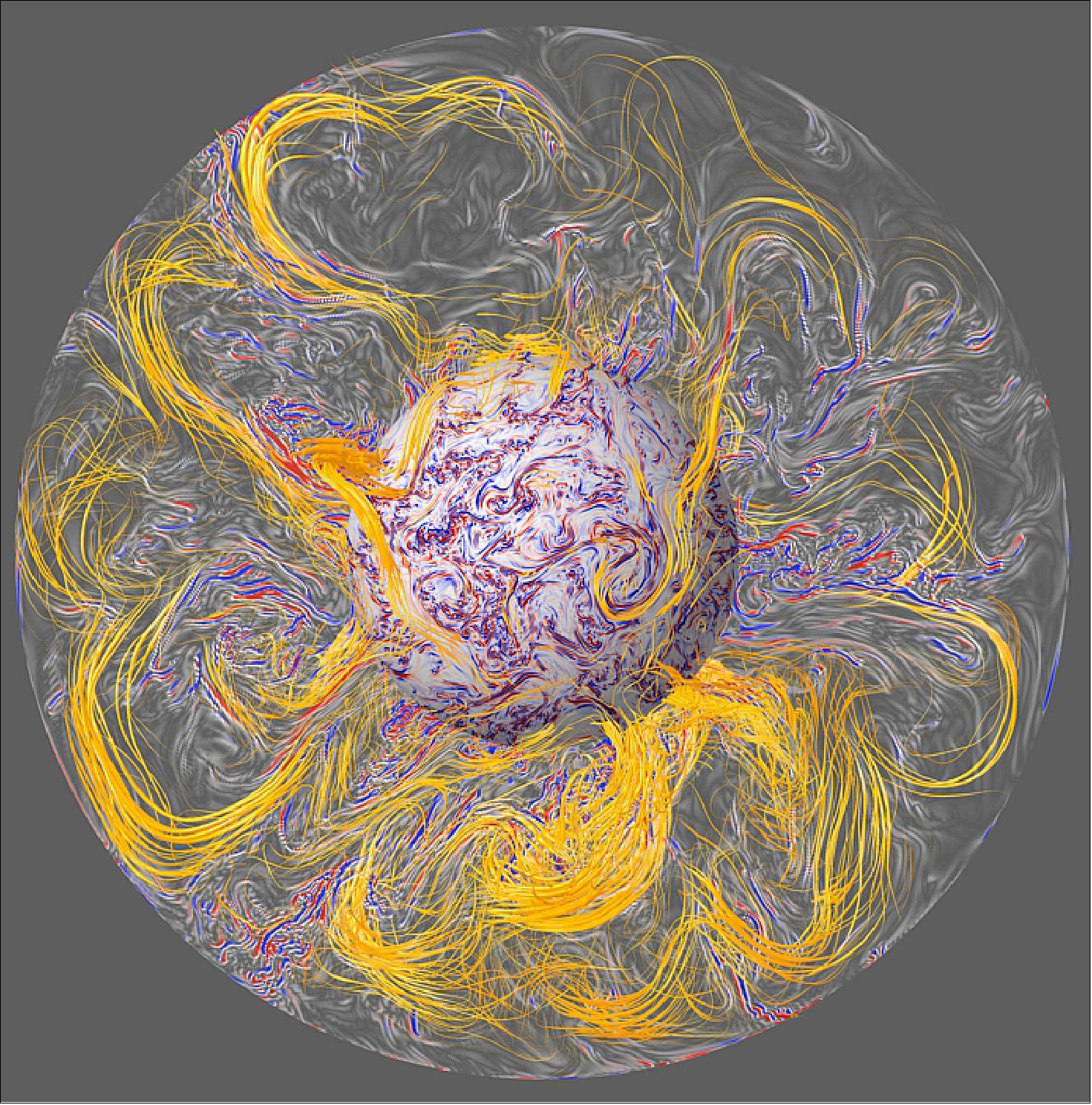

Legend to Figure 6: The magnetic field and electric currents near Earth generate complex forces that have immeasurable impact on our everyday lives. Although we know that the magnetic field originates from several sources, exactly how it is generated and why it changes is not yet fully understood. ESA’s Swarm mission will help untangle the complexities of the field.

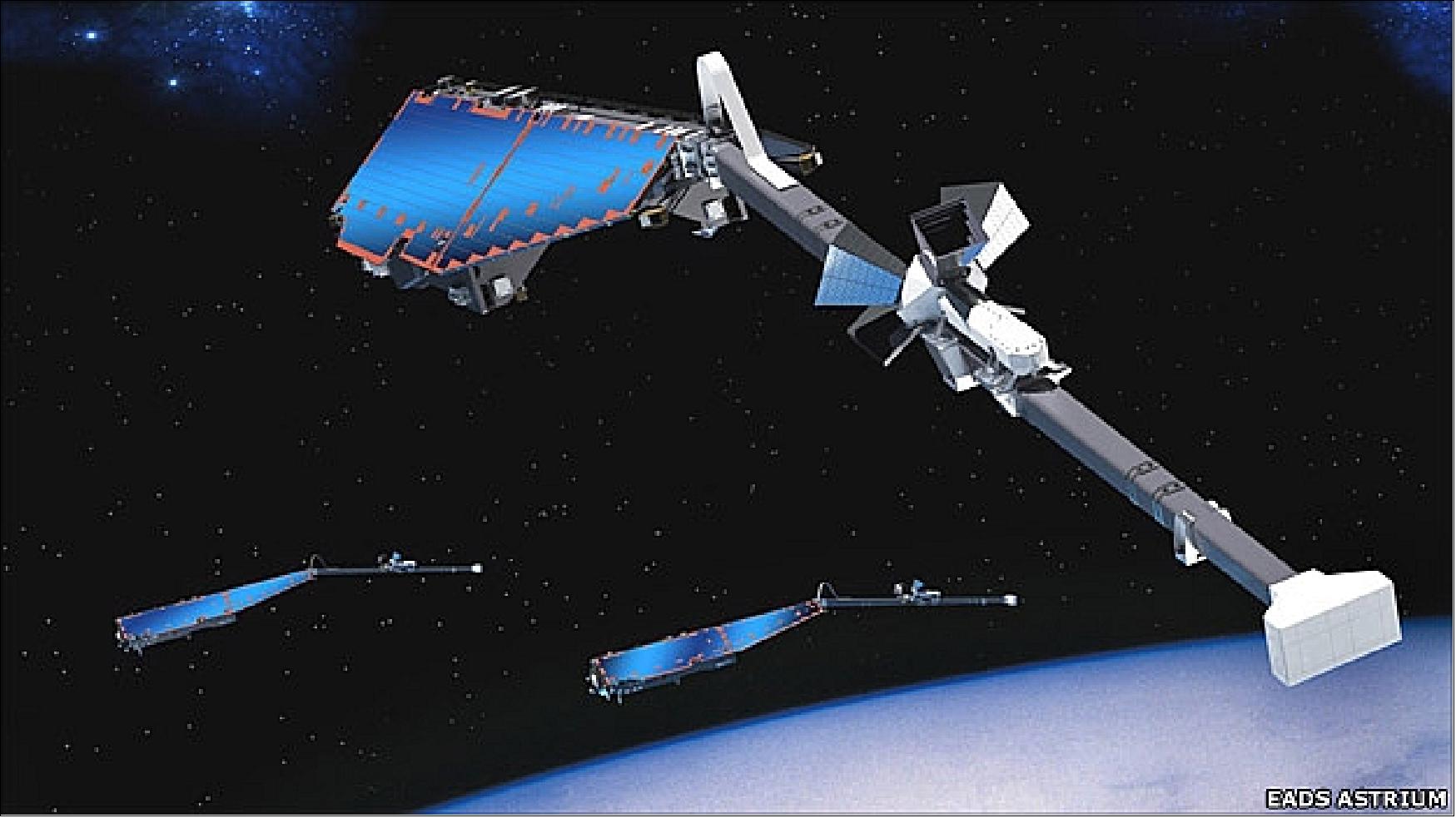

Space Segment Concept

The Swarm mission architecture is driven by the requirement for separation of the various sources contributing to the Earth's magnetic field. Hence, the space segment concept employs a three-minisatellite constellation with the following characteristics:

- Three spacecraft in two different orbital planes, with two satellites in a plane of 84.7º inclination and with one satellite in a plane of 88º inclination

- The two satellites in the 87.4º inclination orbit will fly at a mean altitude of 450 km, their east-west separation will be 1-1.5º, and the maximum differential delay in orbit will be about 10 s.

- The satellite in the higher inclination orbit (88º) will fly at a mean altitude of 530 km.

- The spacecraft require some degree of active orbit maintenance to control the relative positions in the constellation (this is an element of formation flight to support flight operations). 31) 32)

In November 2005, ESA selected EADS Astrium GmbH, Friedrichshafen, Germany as the prime contractor for the Swarm spacecrafts. The Swarm consortium (main subcontractors) consists of: 33)

- EADS Astrium Ltd., UK (mechanical, thermal, AIV)

- GFZ Potsdam, Germany (end-to-end system simulator, calibration & validation)

- DTU Space, Copenhagen, Denmark [level 1b processor and instruments (VFM magnetometer and STR star tracker)]

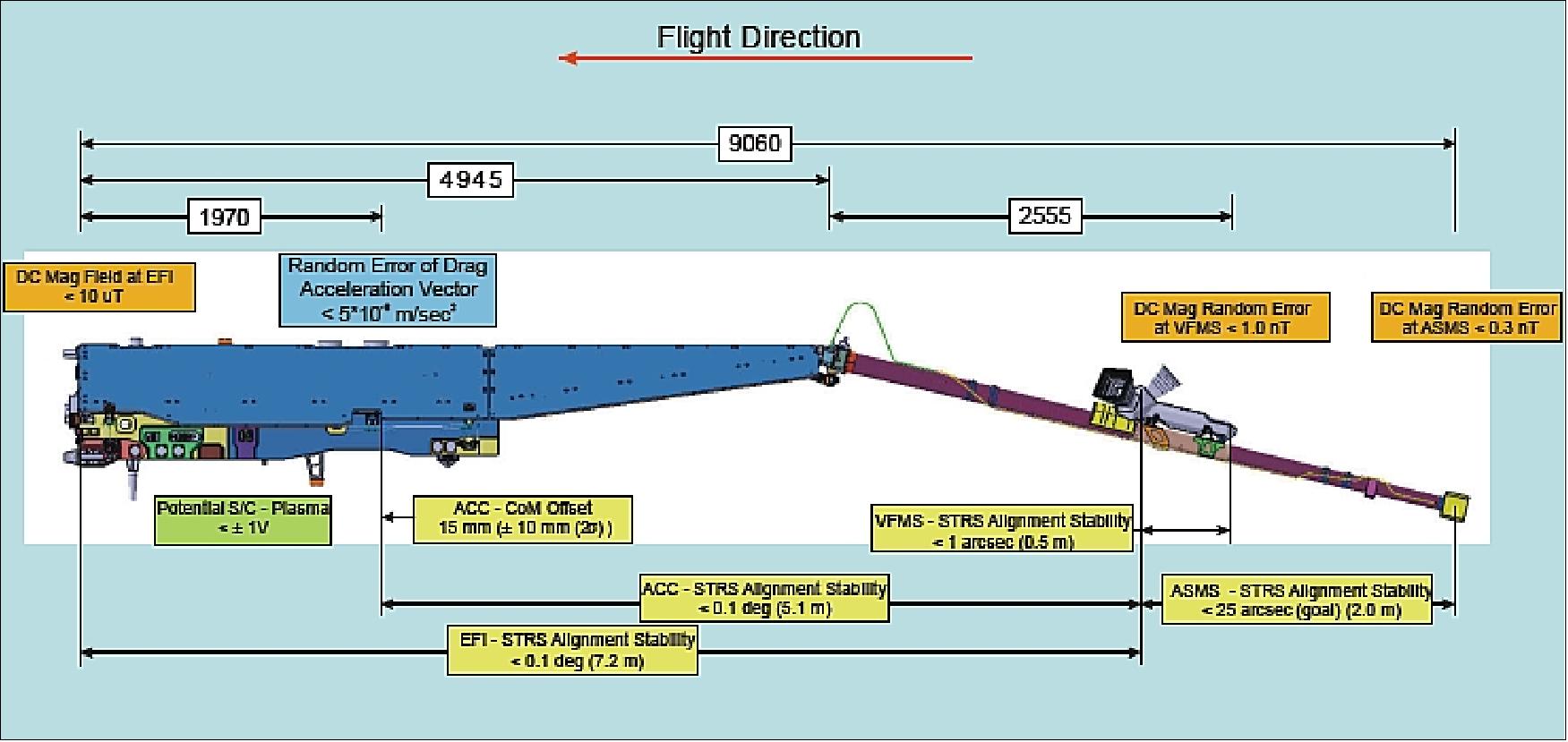

The spacecraft design is governed by the following requirements:

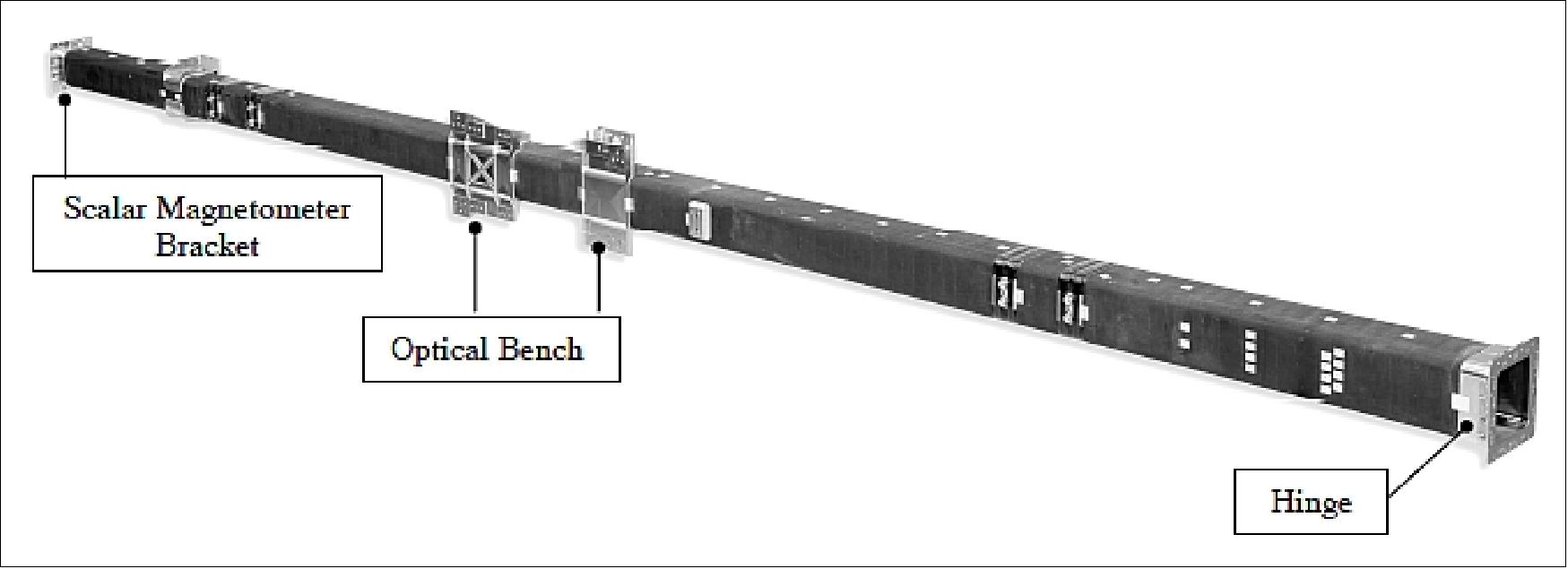

1) Magnetic cleanliness: magnetometers on deployable boom, non-magnetic materials and caution during handling

2) Magnetic field vector attitude knowledge: ultra-stable connection between VFM (Vector Field Magnetometer) and STR (Star Tracker) assembly on the optical bench

3) Ballistic coefficient: small ram surface in flight direction to minimize air drag

4) Accelerometer proof-mass vs satellite CoG (Center of Gravity) location.

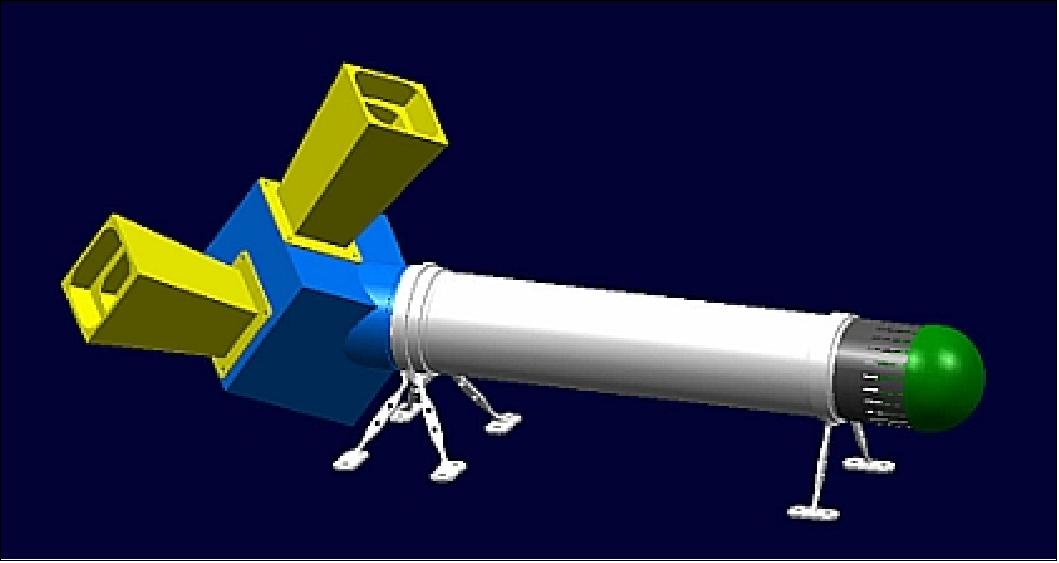

An important design measure is the accommodation of the magnetometer package at a distance from the main body/platform sufficient to minimize any magnetic disturbance. A boom ensures a magnetically 'clean' environment and provides very stable accommodation for the magnetometer package. Due to envelope constraints of the launcher fairing, the boom must be deployable. 34)

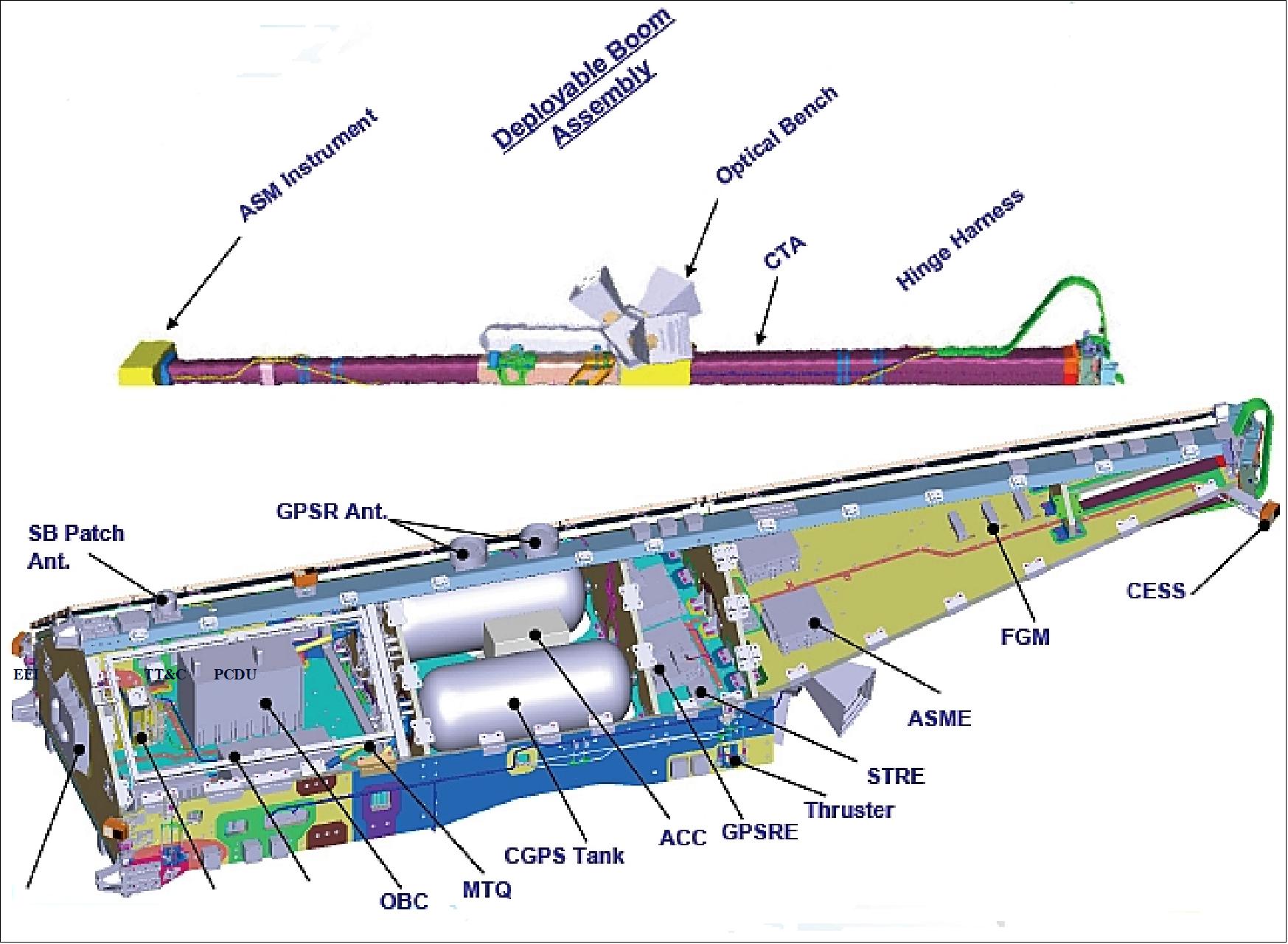

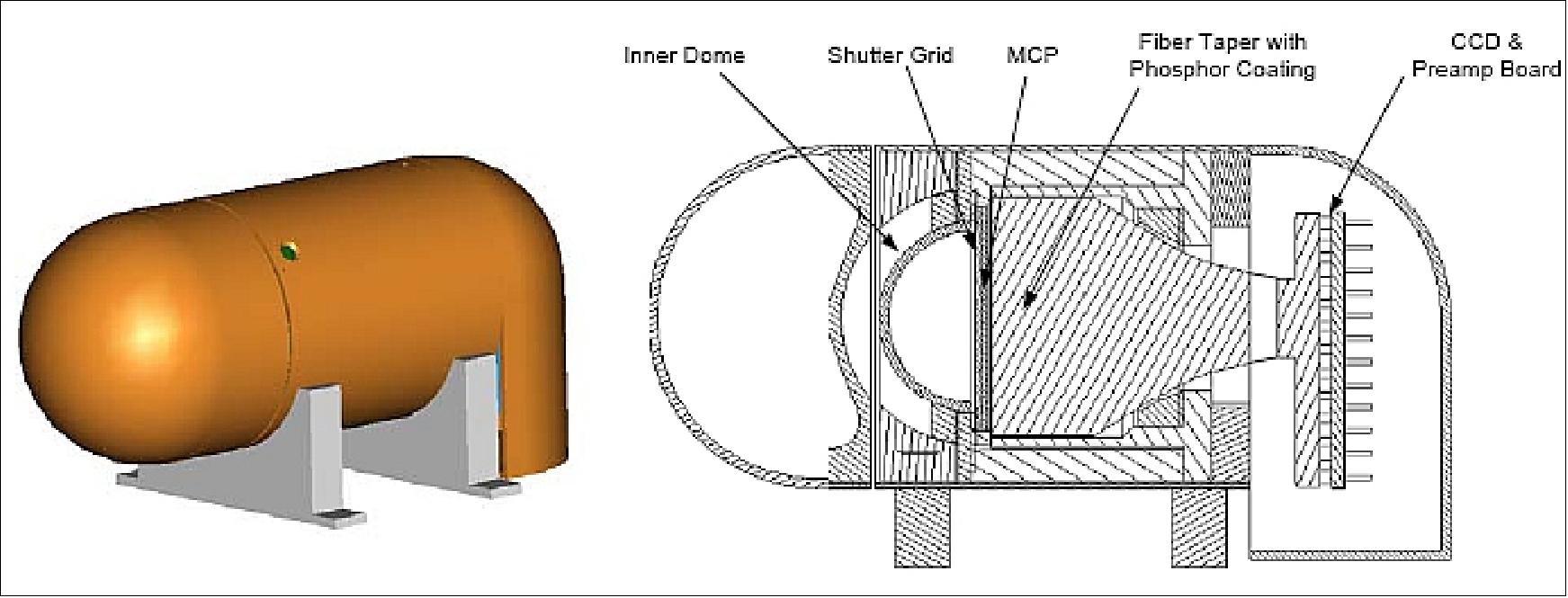

Optical bench: The vector magnetometer is mounted on an ultra-stable silicon carbide-carbon fiber compound structure (the SWARM optical bench). Both optical bench and scalar magnetometer are installed on a deployable conical tube of square cross section. The position tolerance of the optical bench to its tube interface has to be fixed within 0.2 mm. 35) 36)

The design driver of the composite tube assembly of Swarm is thermal stability. The main cause for observed thermal distortion is the non-uniformity of the cross-sections arising from the different adaptations of the filament winding process in order to manufacture the carbon fiber reinforced structure. The manufacture of the structure required use of thermally controlled high precision bonding jigs to join the composite tubes to the metallic fittings.

The scalar magnetometer and optical bench are fixed to a deployable large beam of square cross section, the SWARM (Carbon-fiber Tube Assembly (CTA) which fulfils the following main functions (Figure 8):

• Separate the sensitive instruments from the spacecraft to comply with the very high magnetic cleanliness requirements

• Provide a suitable stable structure for the fixation of instruments.

The chosen manufacturing technology for the SWARM tube was filament winding. The SWARM tube has a conical taper. Since the amount of fibers in a cross section is constant the tube had two main characteristics: the wall thickness increased linearly from the root to the tip and due to nature of the winding process the fiber angle became steeper at the tip than at the root. The overall effect is a variation of properties along the length of the tube.

The Swarm carbon-fiber tube assembly was subjected to various tests: Thermal distortion was measured by establishing a 65ºC gradient between the tip and the hinge and a 10ºC gradient between opposite sides of the CTA. The hole pattern of the optical bench was accurate to within 0.2 mm (Ref. 35).

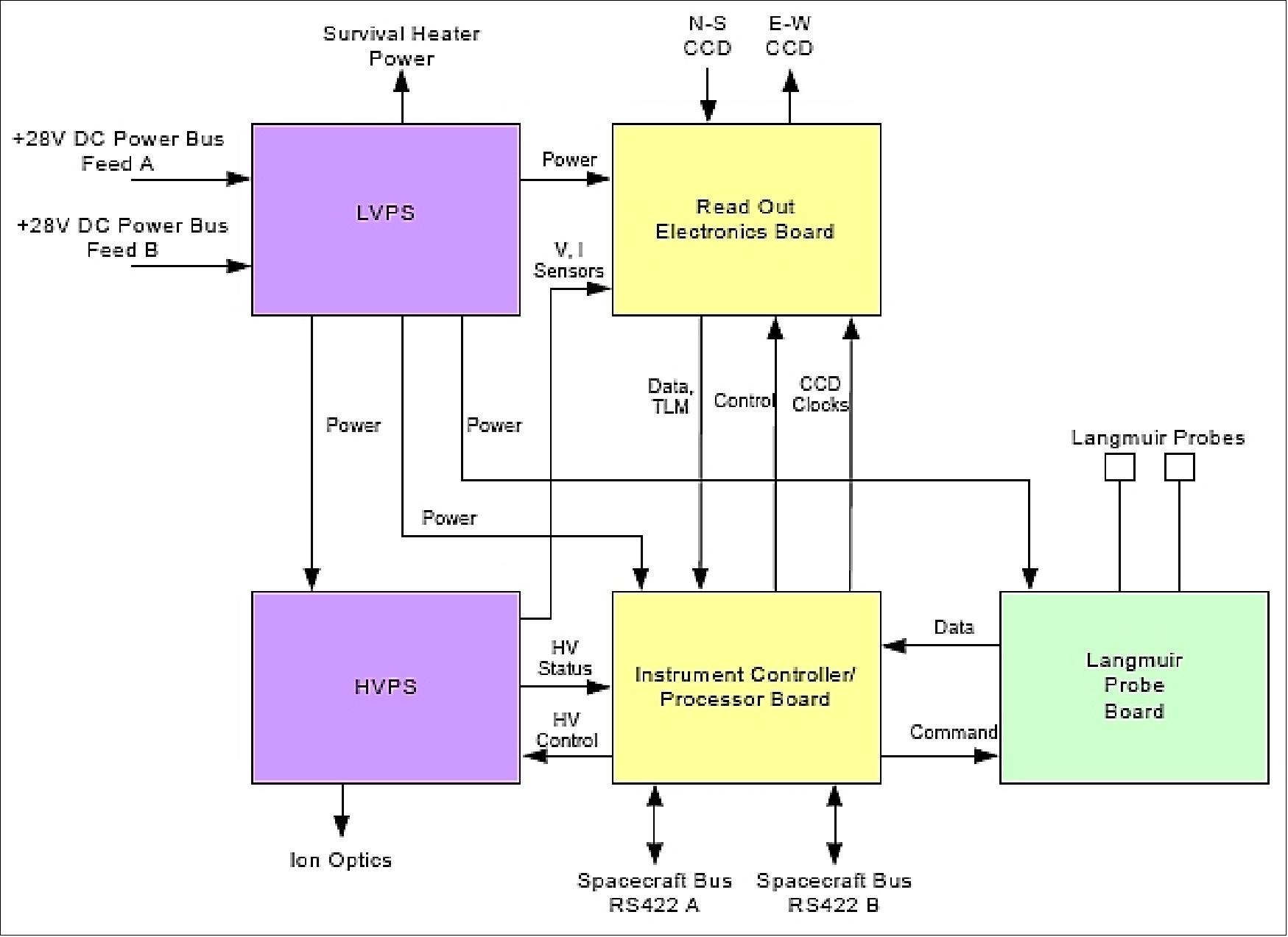

The three identical Swarm minisatellites consist of the payload and the platform elements. The platform comprises the following subsystems: structure/mechanisms, power, RF communications, AOCS (Attitude and Orbit Control Subsystem), thermal control, and onboard data handling.

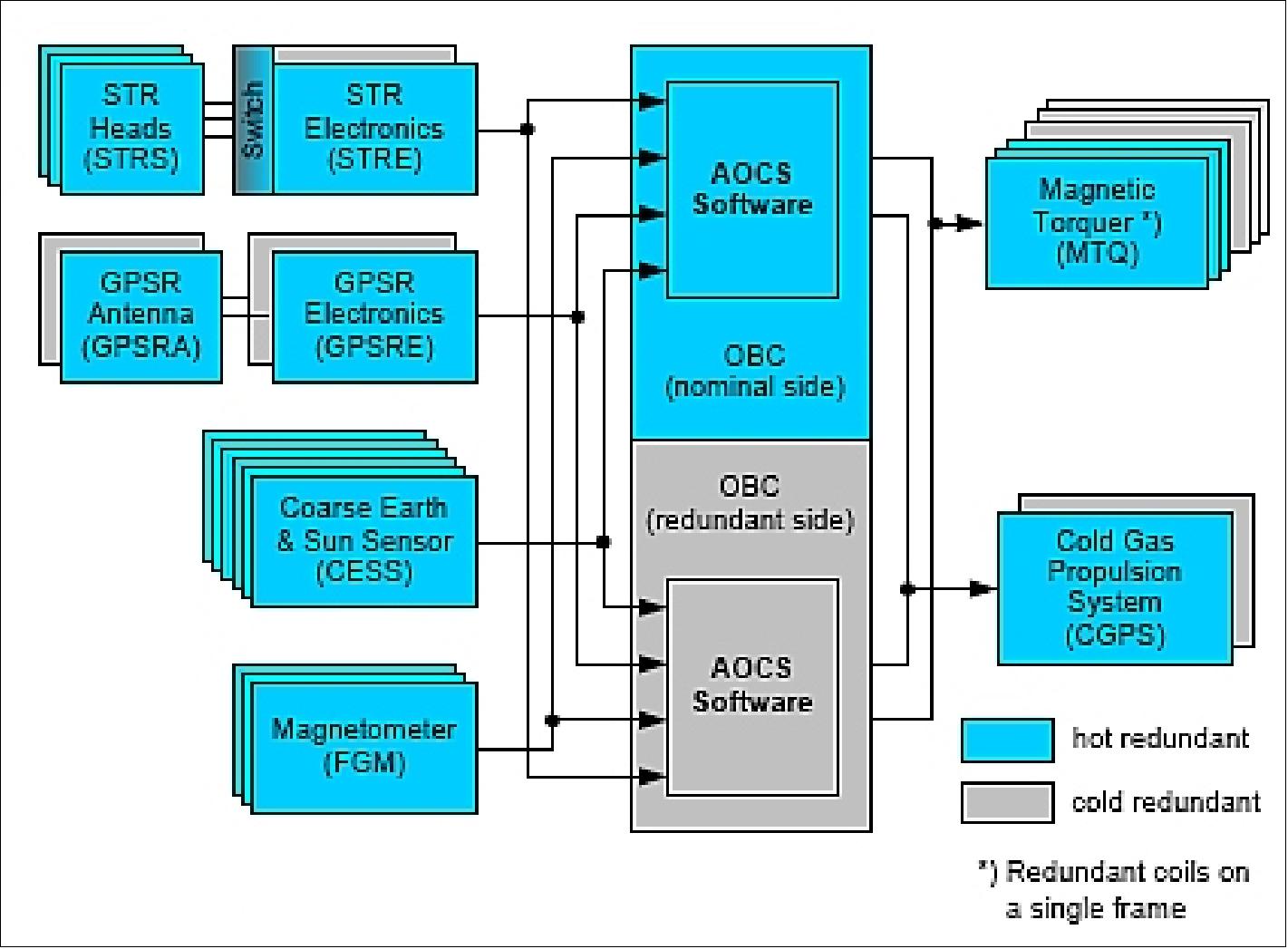

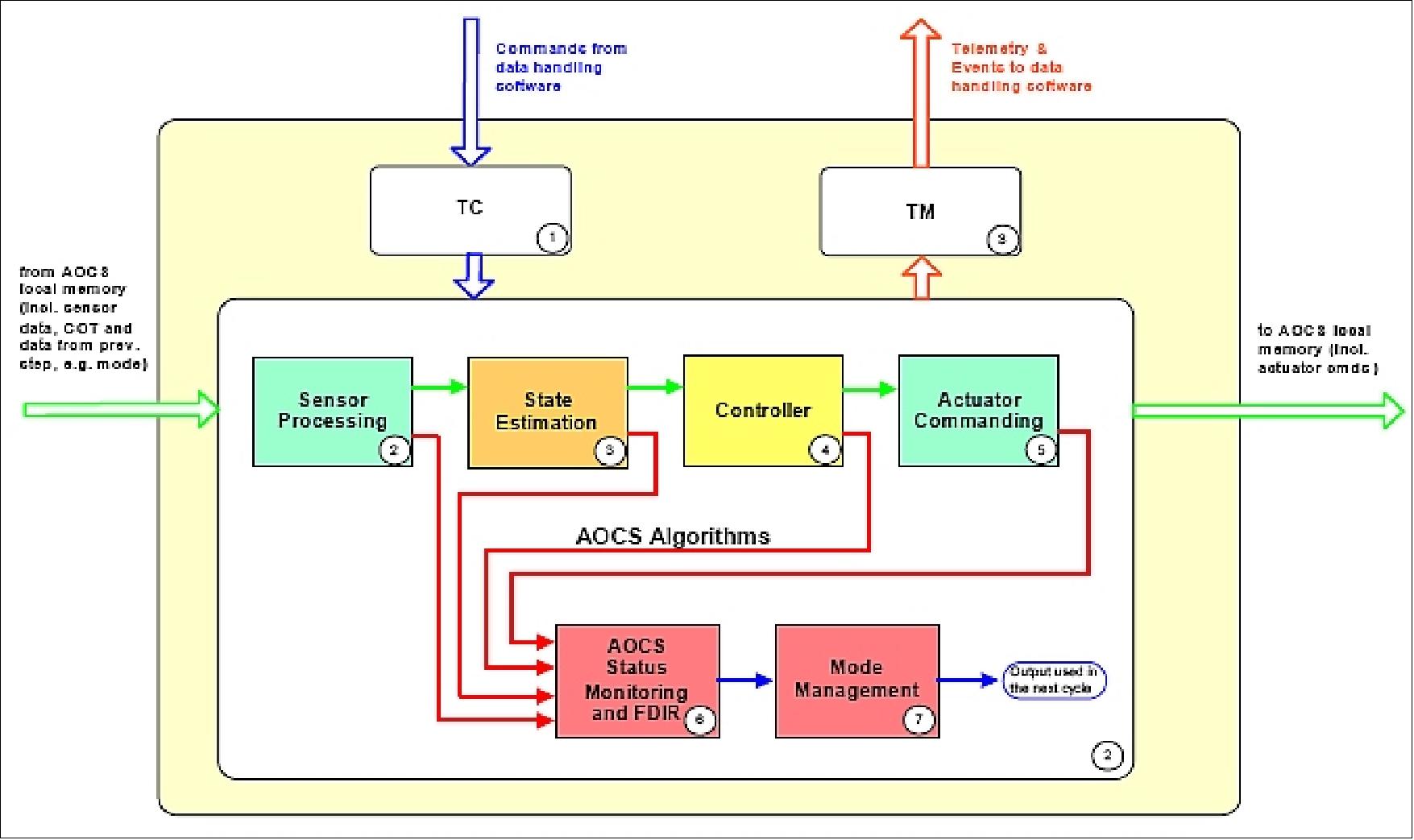

The AOCS design is based to a maximum extent on the CryoSat AOCS design of EADS Astrium. The gyro-less AOCS provides 3-axis stabilization with an Earth pointing attitude control in all modes. The requirements call for: 37)

- An attitude pointing control within a band of < 5º about all axis (roll, pitch, and yaw), the pointing stability is < 0.1º/s

- Provision of a sufficient torque capability for launcher tip-off rate damping and attitude acquisition

- Minimize acceleration and magnetic stray field disturbances to scientific instruments

- Provision of a high ΔV capability for orbit & attitude control maneuvers.

The AOCS is tightly coupled with the propulsion subsystem. Actuation is provided by a cold gas propulsion subsystem, referred to as OCS (Orbit Control Subsystem), and magnetic torquers (used for ΔV maneuvers and to complement the magnetic torquers). The cold gas propulsion system is provided by AMPAC-ISP, UK. - Attitude sensing is provided by a star tracker assembly (3 star tracker heads), 3 magnetometers, and a CESS (Coarse Earth and Sun Sensor) assembly used in safe mode situations and in initial acquisition sequences, respectively (CESS is of CHAMP, GRACE, and TerraSAR-X heritage). A dual frequency GPS receiver (GPSR) is used to provide PPS (Precise Positioning Service) to the OBC and instruments for on-board datation.

Note: the star tracker (STR) assembly and optical bench are described below under a separate heading.

The nominal attitude has a nadir orientation. Rotation maneuvers of S/C about roll, pitch and yaw are used for instrument calibration and orbit Control. The safe mode is Earth-oriented. Pointing requirements are 2º about all axes, with limitations on use of actuators.

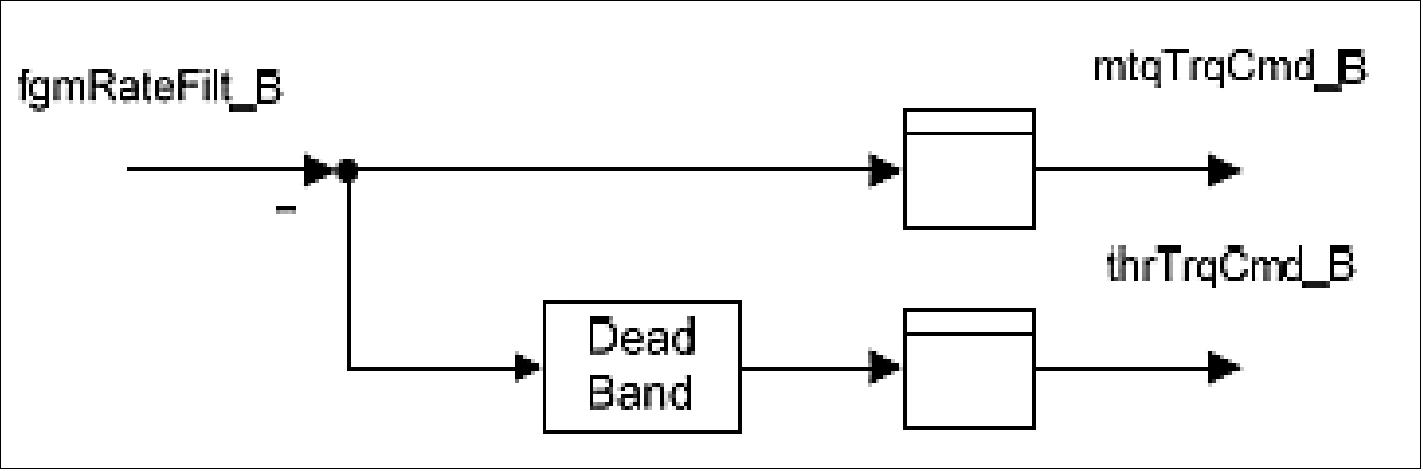

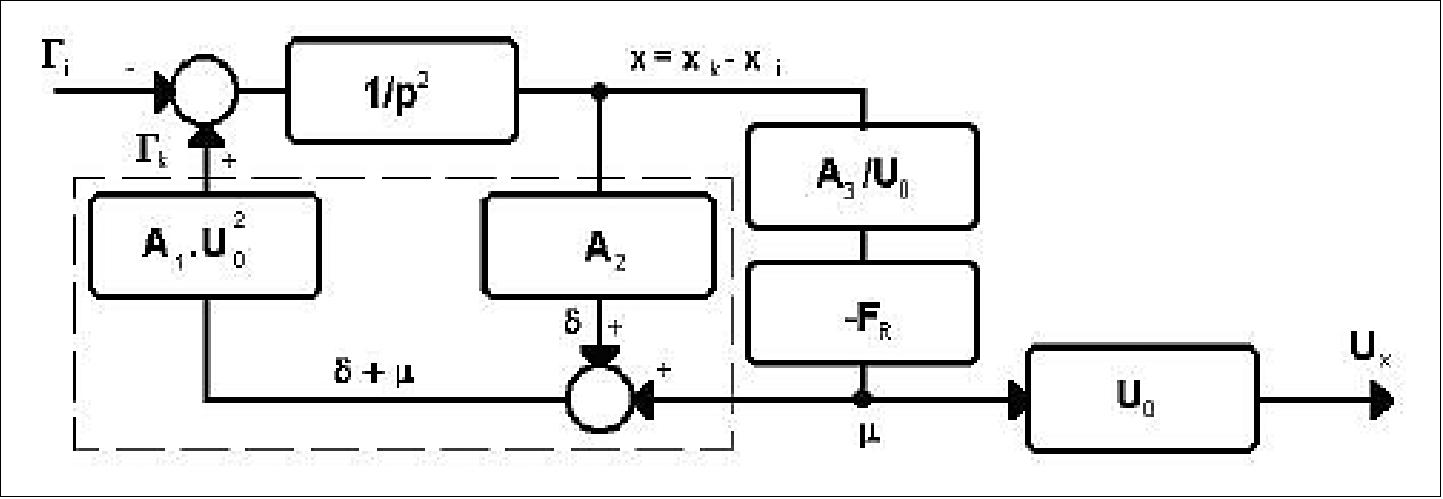

The Swarm rate damping design, in support of the critical spacecraft deployment phase, employs magnetic rate damping - magnetometers in combination with magnetic torquers and thrusters - to provide a significantly cheaper implementation than with the use of gyroscopes. From a control theory point-of-view, rate damping with magnetometers using 2-axis measurement is as “safe” as with gyroscopes using 3-axis measurement: Global asymptotical stability is achieved except for the case when the magnetic field does not change. This is only in near-equator orbits possible with perfect field symmetry which is in practice not realistic. The result is confirmed by the evaluation of the observability criterion where no loss of this property could be detected except for the mentioned case. Since SWARM is in a polar inclination orbit, the control concept is considered “clean”. 38)

Rate damping design: The RDM controller is a simple proportional controller on the S/C rate with reference rate zero. The S/C rate is computed by processing and derivation of the FGM measurements. The controller outputs the torque commands for the torquer and the thruster. A dead band for the thruster inhibits the thruster activation for low rates which can be covered by the torque rod.

Each spacecraft features 2 propellant tanks, each with a capacity of 30 kg of N2. The thrusters provide thrust levels of 20 and 40 mN. The cold gas thruster system was developed and space qualified by Ampec-ISP, Cheltenham, UK consisting of 24 OCT (Orbit Control Trusters) and 48 ACT (Attitude Control Thrusters) for the Swarm constellation. The assembly and test of Ampac's SVT01 series of cold gas thrusters has included design modifications, full qualification and verification of suitability to operate with a new propellant. In 2010, a set of 72 units has been supplied and integrated into the constellation of three Swarm spacecraft. 39)

A GPS receiver provides the functions of timing and position determination. The spacecraft dry mass is about 370 kg.

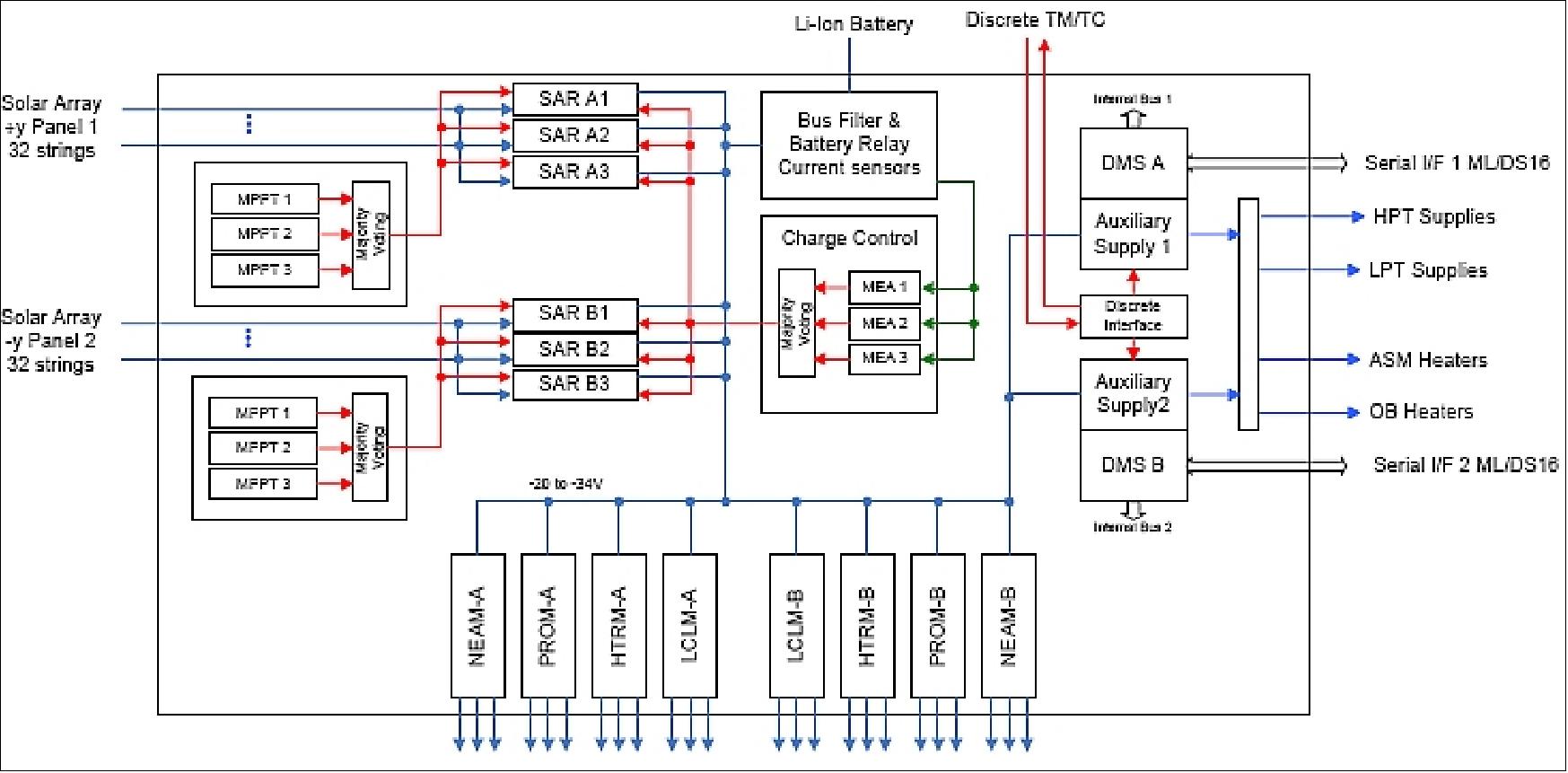

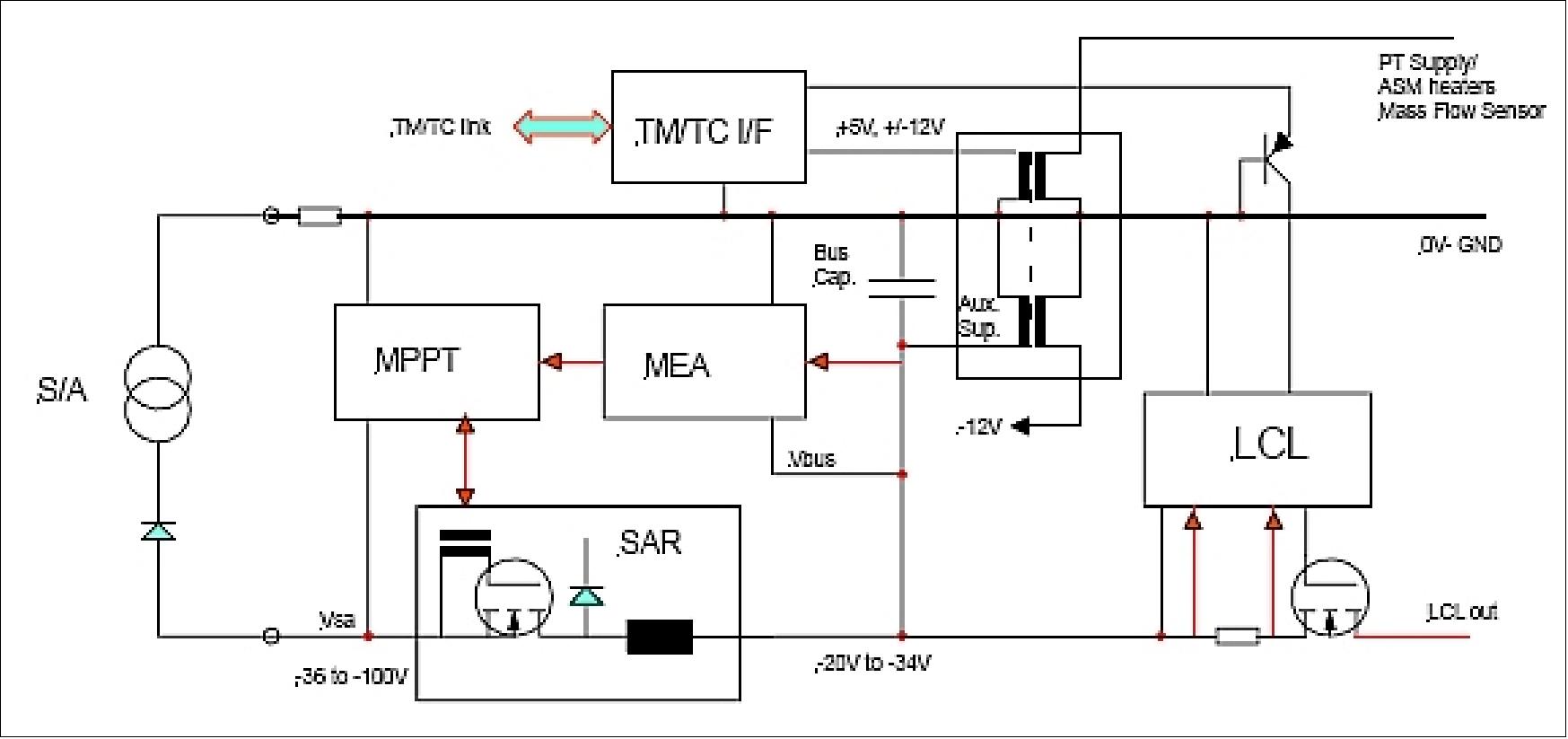

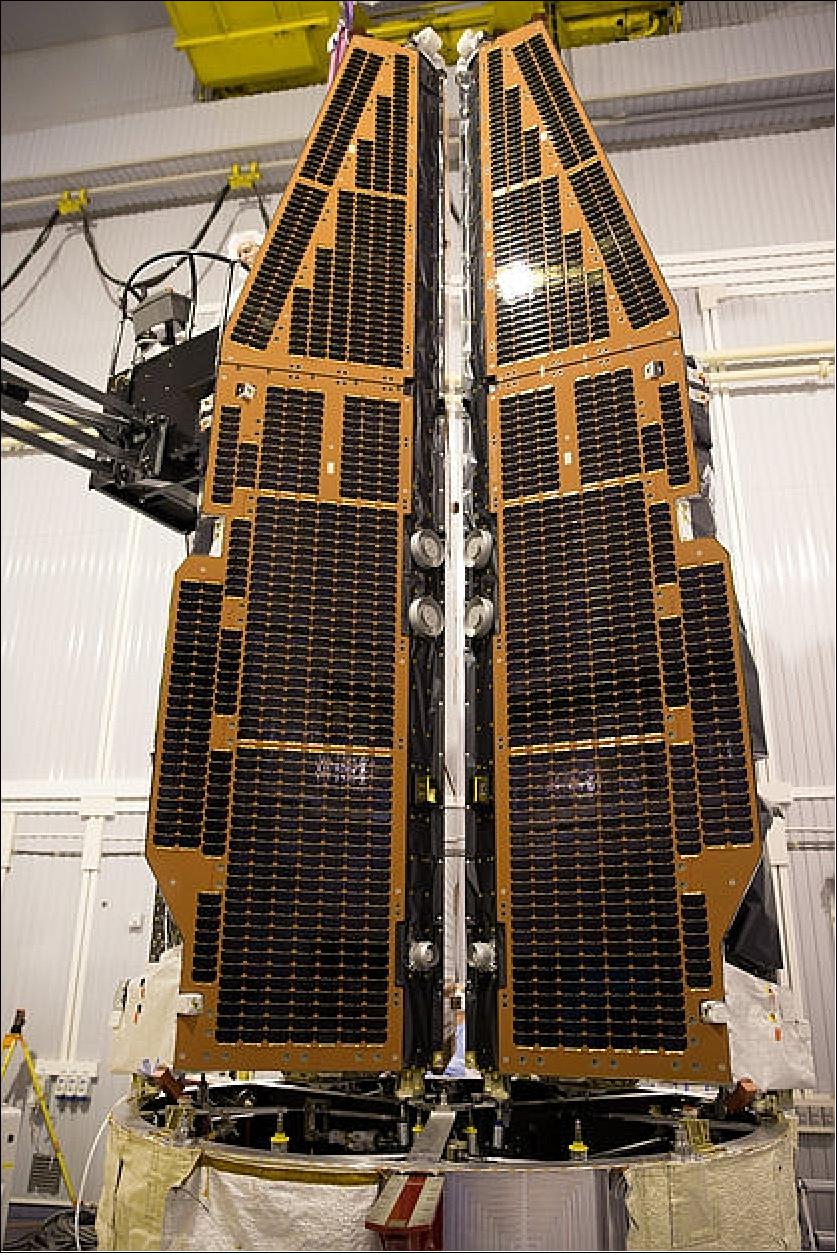

EPS (Electrical Power Subsystem): The two body-mounted solar arrays and the varying orbits of the satellites require a MPPT (Maximum Power Point Tracking) system. Important requirements are related to the magnetic cleanliness of the satellites and result in following specific PCDU (Power Conditioning and Distribution Unit) design requirements: 40)

- Minimization of magnetic moment i.e. minimizing of magnetic materials and current loops

- Selection of switching frequencies outside the ‘forbidden’ frequency ranges

- Minimizing spacecraft surface charging by use of negative bus voltage concept (battery + is connected to spacecraft structure).

The PCU part of the PCDU covers all tasks to control the power flow in the unit from the different sources and performs the communication with the OBC (On Board Computer).

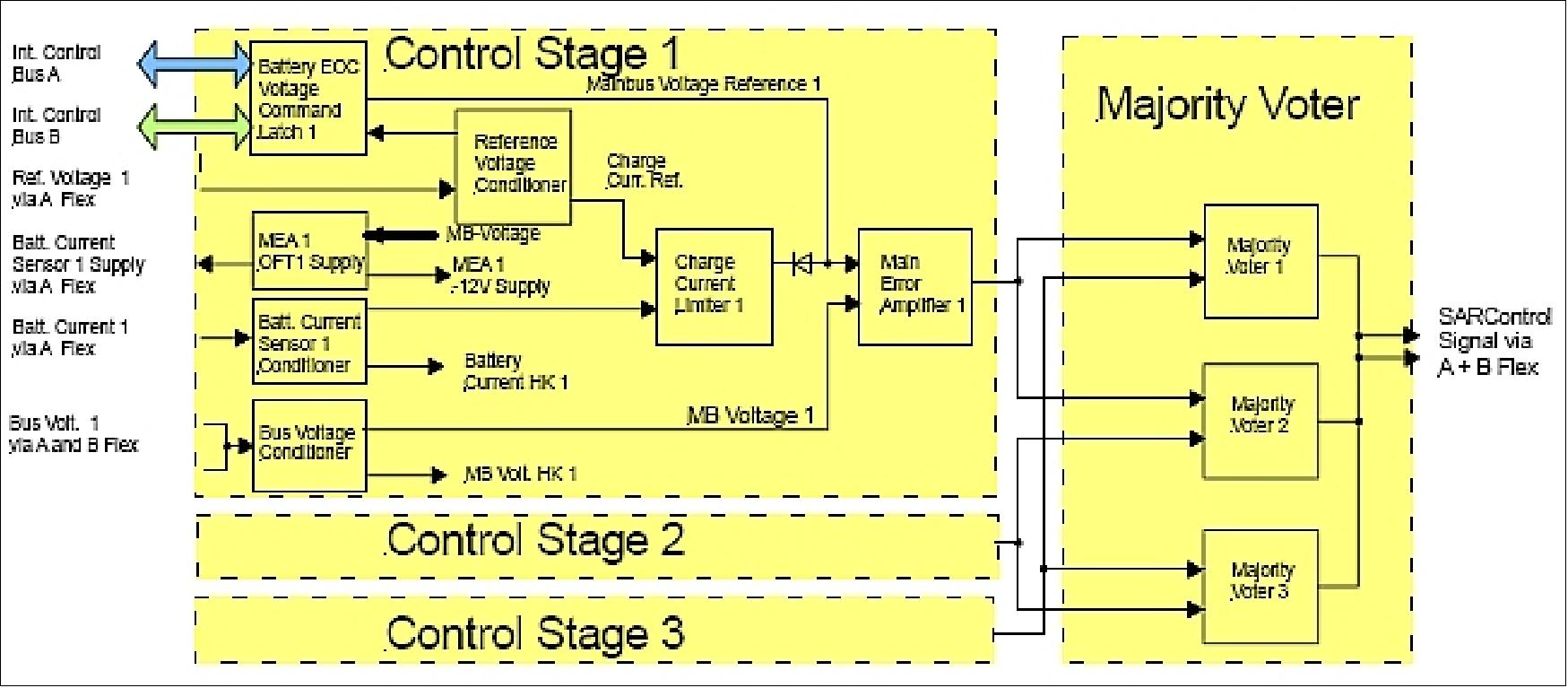

During eclipse and battery recharge mode, the bus voltage varies with the state of charge of the battery. In taper charge mode, the bus is controlled by the MEA (Main Error Amplifier) to a predefined (commandable) value.

The main power requirements for the PCDU are defined as follows:

- Solar array input: 0 to -125 V, max. 21 A (each of 2 panels)

- Maximum power per panel: 750 W

- Main bus voltage range -22 V to -34 V

- Maximum battery charge current 24 A

- Continuous discharge current 0 to 14 A.

Maximum discharge current/power up to 0.5 h: 20 A / 440 W.

Negative bus voltage concept: The Swarm satellite requires the positive line of the power system connected to structure. This implies that all bus protection functions have to be allocated in the ‘hot’ negative line. As all essential functions, ( i.e. bus voltage control) need to be independent from the auxiliary supplies, they have to be supplied by the negative bus voltage. Figure 15 shows a principle grounding/power supply diagram of the main functional blocks in the PCDU.

Power control concept: The PCDU uses a simple concept for control of the battery state of charge and the bus voltage:

- Whenever the bus voltage and the charge current are below the limits, the MPPTs are active

- When the either the bus voltage attains the ‘battery end-of-charge voltage or the battery attains the charge current limit, the MEA (Main Error Amplifier) supersedes the tracker operation.

A bus overvoltage detection logic has been implemented in the PCDU, which performs a rapid ramp-down of the solar regulator current by using hysteresis control.

The MEA is composed of 3 identical separated control stages and a majority voter. Each control stage has a dedicated set of sensors and receives the relevant set commands for the bus voltage via redundant internal control busses. The charge current limitation is implemented in a ‘cascade configuration’, using the output of the current error amplifier as a set signal for the voltage amplifier. This assures a low and constant bus impedance during all MEA control modes. The implementation of the regulation concept is given in Figure 16.

Spacecraft mass | Dry mass of ~369 kg |

Spacecraft dimensions | Length: 9.1 m; width: 1.5 m (S/C body); height: 0.85 m; ram surface: ~0.7 m2 |

Boom length | 5.1 m |

AOCS | - 3-axis stabilized; magnetometers; CESS; GPS; STR, magnetorquers; thrusters |

AOCS sensors | - STR (Star Tracker) with 3 sensor heads |

AOCS control modes | - Rate damping: rates are measured by the FGMs, main actuation by THR |

EPS (Electrical Power Subsystem) | Total power: 608 W nominal; solar cells: GaAs triple junction; solar panel positive grounding; a set of batteries: Li-ion with a capacity of 48 Ah |

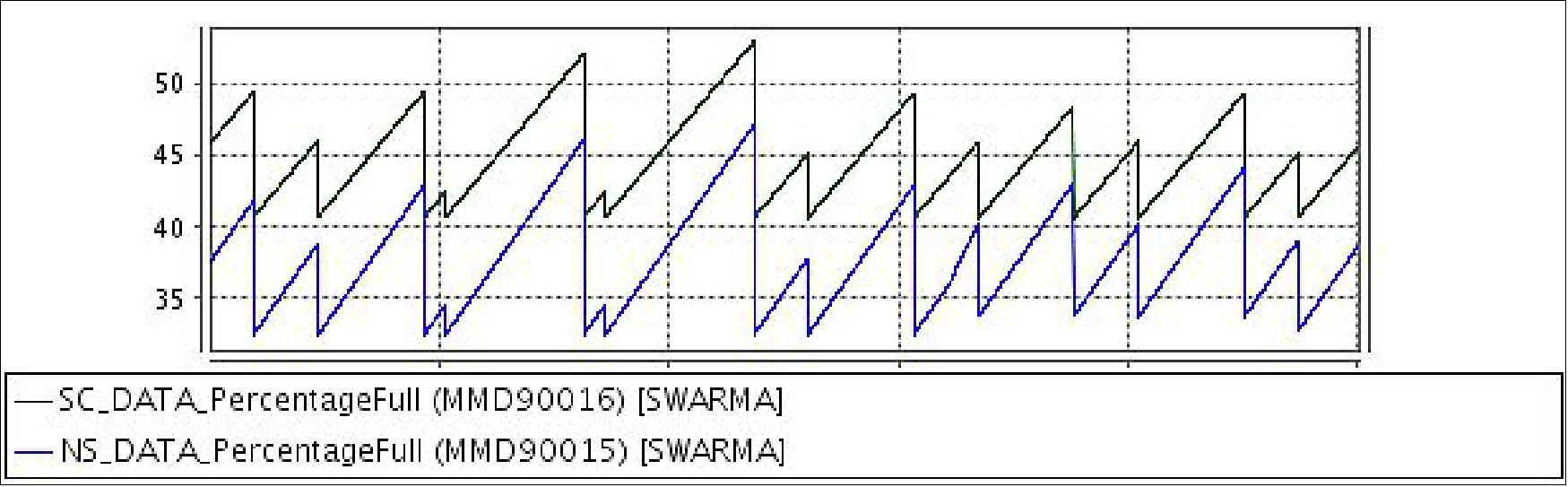

RF communications | S-band; downlink data rate: 6 Mbit/s; 4 kbit/s uplink, data volume: 1.8 Gbit/day; 1 dump/day to Kiruna ground station, data storage capability: 2 x 16 Gbit |

Mission duration | 3 months of commissioning followed by 4 years of nominal operations |

RF communications: S-band for TT&C spacecraft monitoring services and for science data transmission.

Legend to Figure 19: Attached to the tailor-made launch adapter, the three Swarm satellites sit just centimeters apart. This novel part of the rocket keeps the satellites upright within the fairing during launch and allows them to be injected simultaneously into orbit. 41)

DBA (Deployable Boom Assembly): The Swarm DBA, consisting of a 4.3m long CFRP tube and a hinge assembly, is designed to perform this function by deploying the CFRP tube plus the instruments mounted on it. mounted on a 4.3m long deployable boom. Deployment is initiated by releasing 3 HDRMs (Hold Down Release Mechanisms) , once released the boom oscillates back and forth on a pair of pivots, similar to a restaurant kitchen door hinge, for around 120 seconds before coming to rest on 3 kinematic mounts which are used to provide an accurate reference location in the deployed position. The motion of the boom is damped through a combination of friction, spring hysteresis and flexing of the 120+ cables crossing the hinge. Considerable development work and accurate numerical modelling of the hinge motion was required to predict performance across a wide temperature range and ensure that during the 1st overshoot the boom did not damage itself, the harness or the spacecraft. - Due to the magnetic cleanliness requirements of the spacecraft, no magnetic materials could be used in the design of the hardware. 42)

Launch

The Swarm constellation was launched on Nov. 22, 2013 (12:02:29 UTC) on a Rockot vehicle from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome, Russia. The launch was provided by Eurockot Launch Services. Some 91 minutes after liftoff, the Breeze-KM upper stage released the three satellites into a near-polar circular orbit at an altitude of 490 km. 43) 44) 45) 46) 47)

The launch was planned for the fall of 2012, but due to the recent Breeze-M (Briz-M) failure the launch was postponed to permit proper investigations of the cause. In Nov. 2012, ESA is still expecting, from the Russian Ministry of Defence, the launch manifest for the year 2012/13 for Rockot launchers indicating the launch date for Swarm. 48) 49)

Note: Rockot, a converted SS-19 ballistic missile, has been grounded since February 1, 2011 when the Rockot vehicle with the Breeze-KM upper stage failed to place the Russian government’s GEO-IK2 geodesy satellite of 1400 kg (Kosmos 2470) into its intended orbit of 1000 km. However, in the meantime, the Rockot/Breeze-KM vehicle demonstrated its reliability by lifting 4 Russian spacecraft (Gonets-M No.3, Gonets-M No.4, Strela-3/Rodnik, and Yubileiny-2/MiR) successfully into orbit on July 28, 2012.

On April 9, 2010, ESA awarded a contract to Eurockot, for the launch of two of its Earth observation missions. The contract covers the launch of ESA's Swarm magnetic-field mission and a 'ticket' for one other mission, yet to be decided. Both will take place from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome in northern Russia using a Rockot/Breeze-KM launcher. Eurockot is based in Bremen, Germany and is a joint venture between Astrium and the Khrunichev Space Center, Moscow. 50) 51) 52) 53)

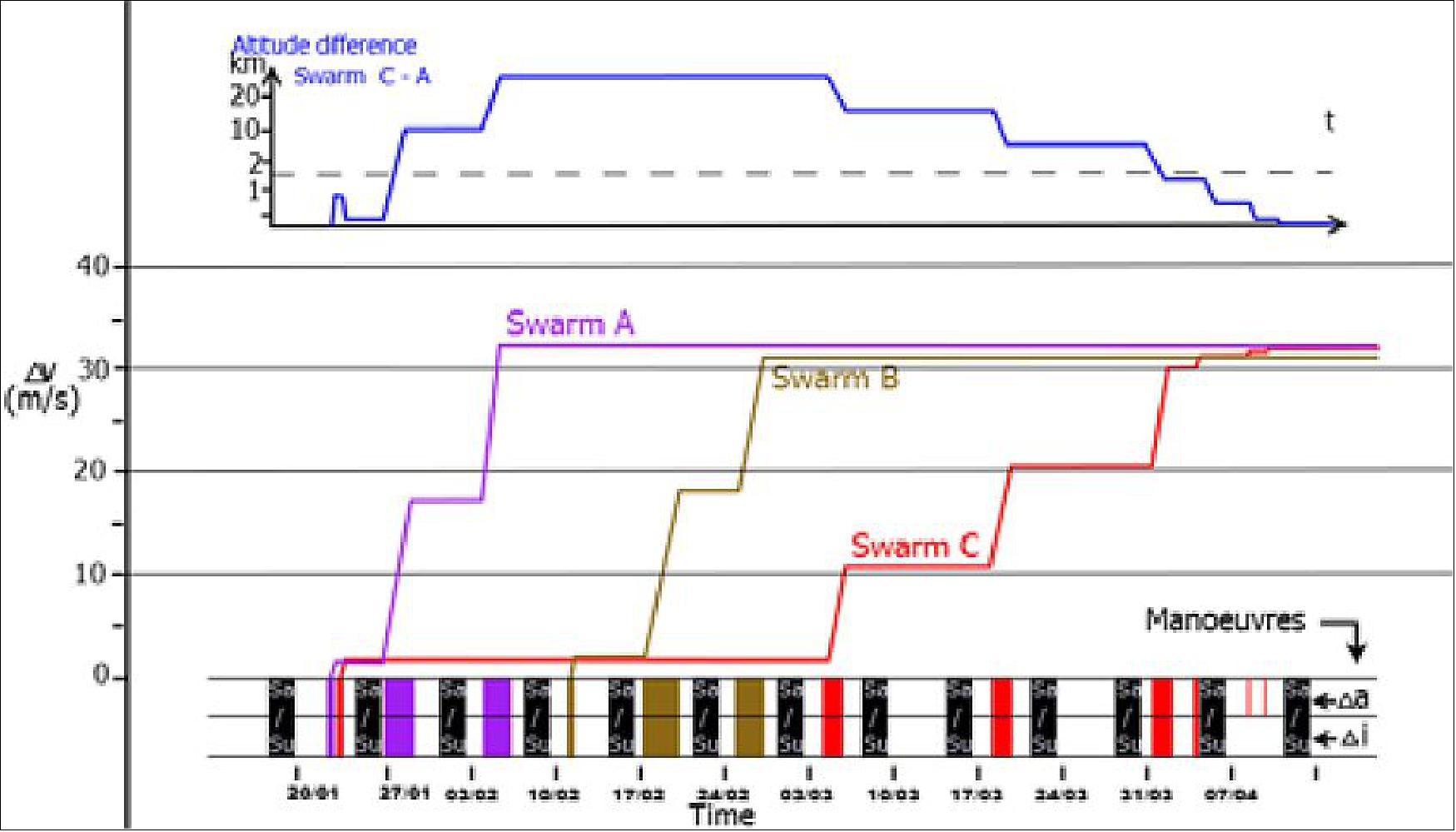

After release from a single launcher, a side-by-side flying lower pair of satellites at an initial altitude of 460 km and a single higher satellite at 530 km will form the Swarm constellation. The constellation deployment and maintenance require a total ΔV effort of about 100 m/s.

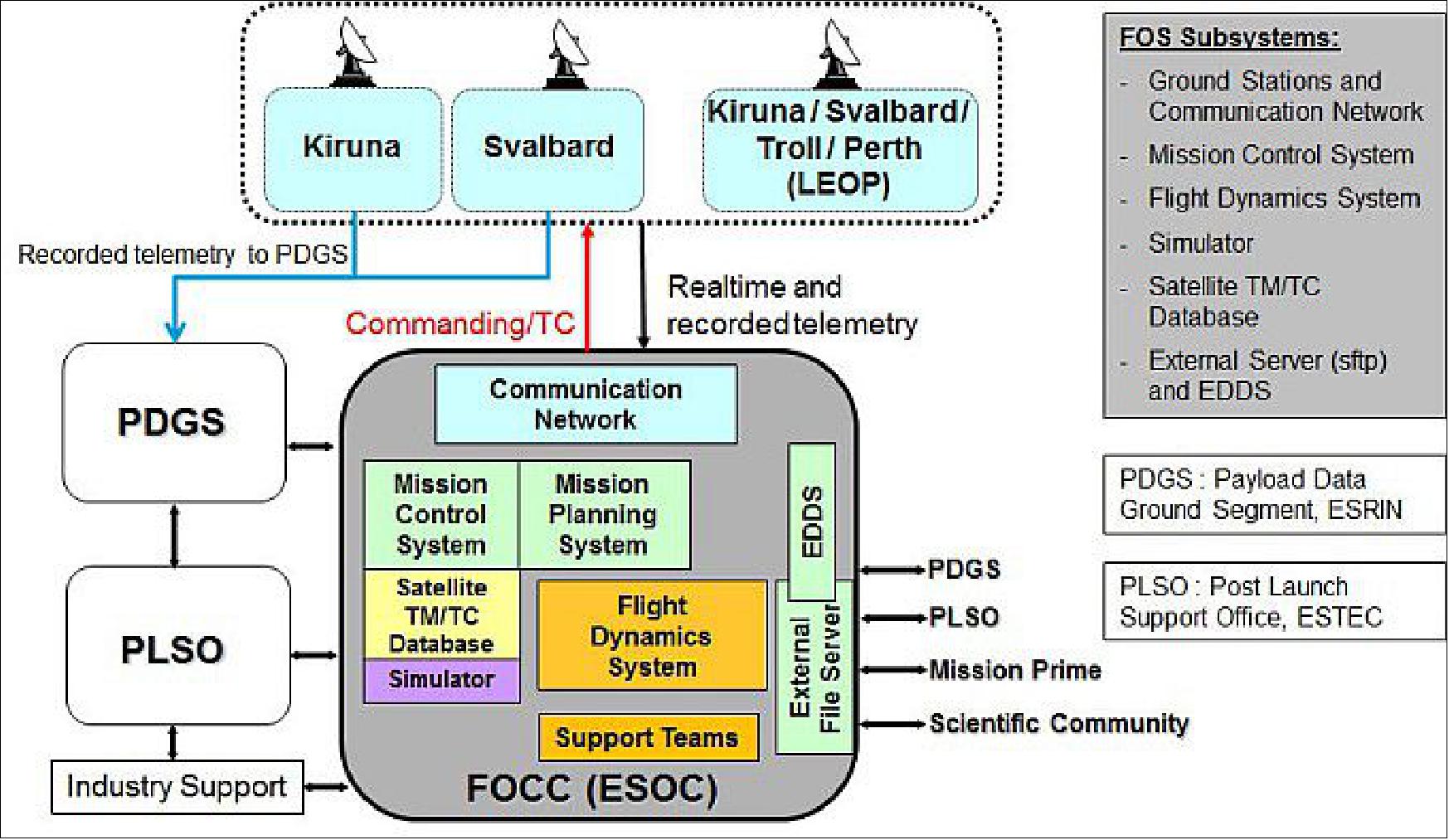

In LEOP (Launch and Early Orbit Phase), at least three ground stations will be involved. LEOP is expected to last 3 days for the full activation of the satellites, followed by an orbit acquisition phase of up to three months. In parallel with the orbit acquisition phase, the commissioning phase will start in order to check out all satellite subsystems and the payload. The commissioning phase is currently expected to last three months. After the commissioning phase the nominal mission phase of 4 year starts.

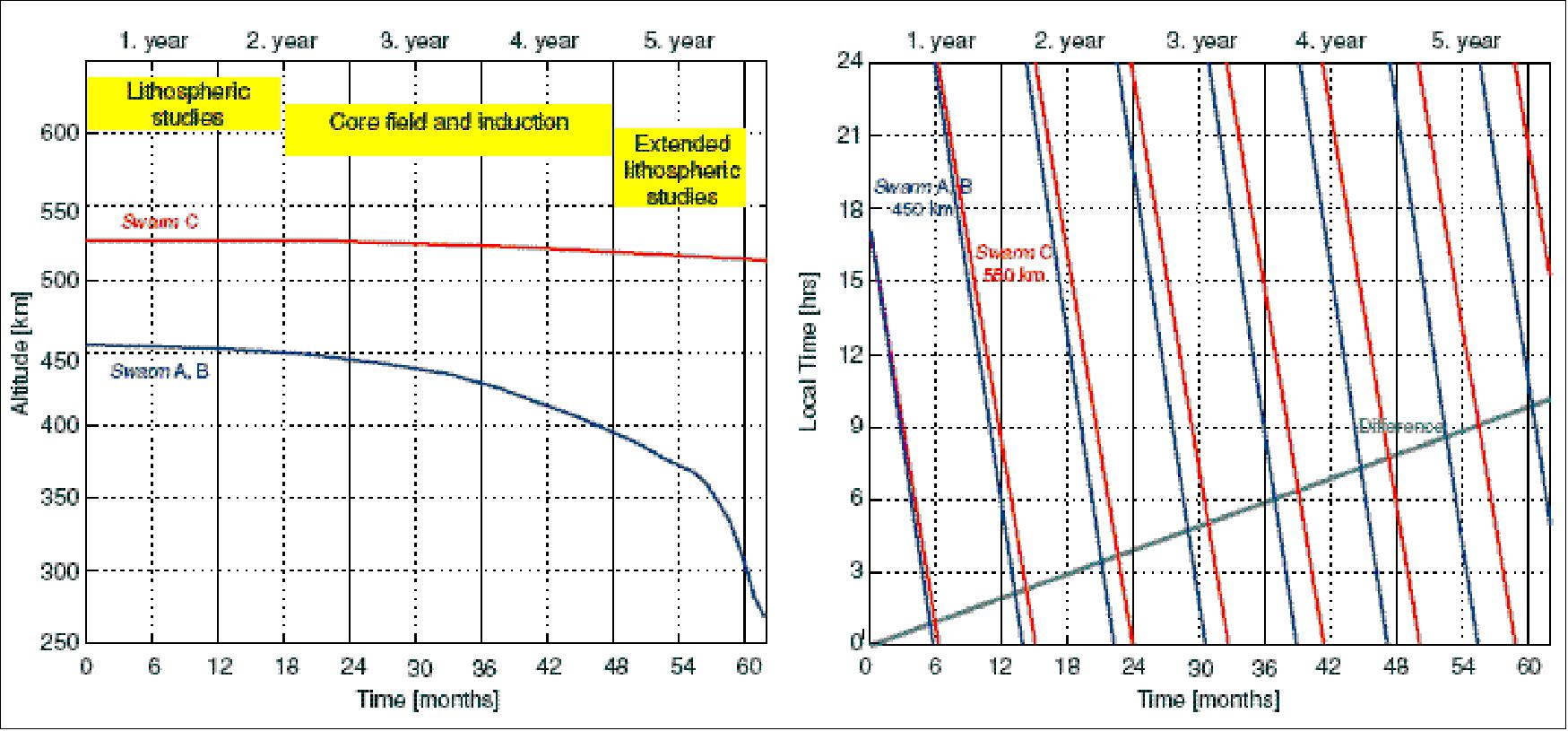

Orbits of the Swarm Constellation

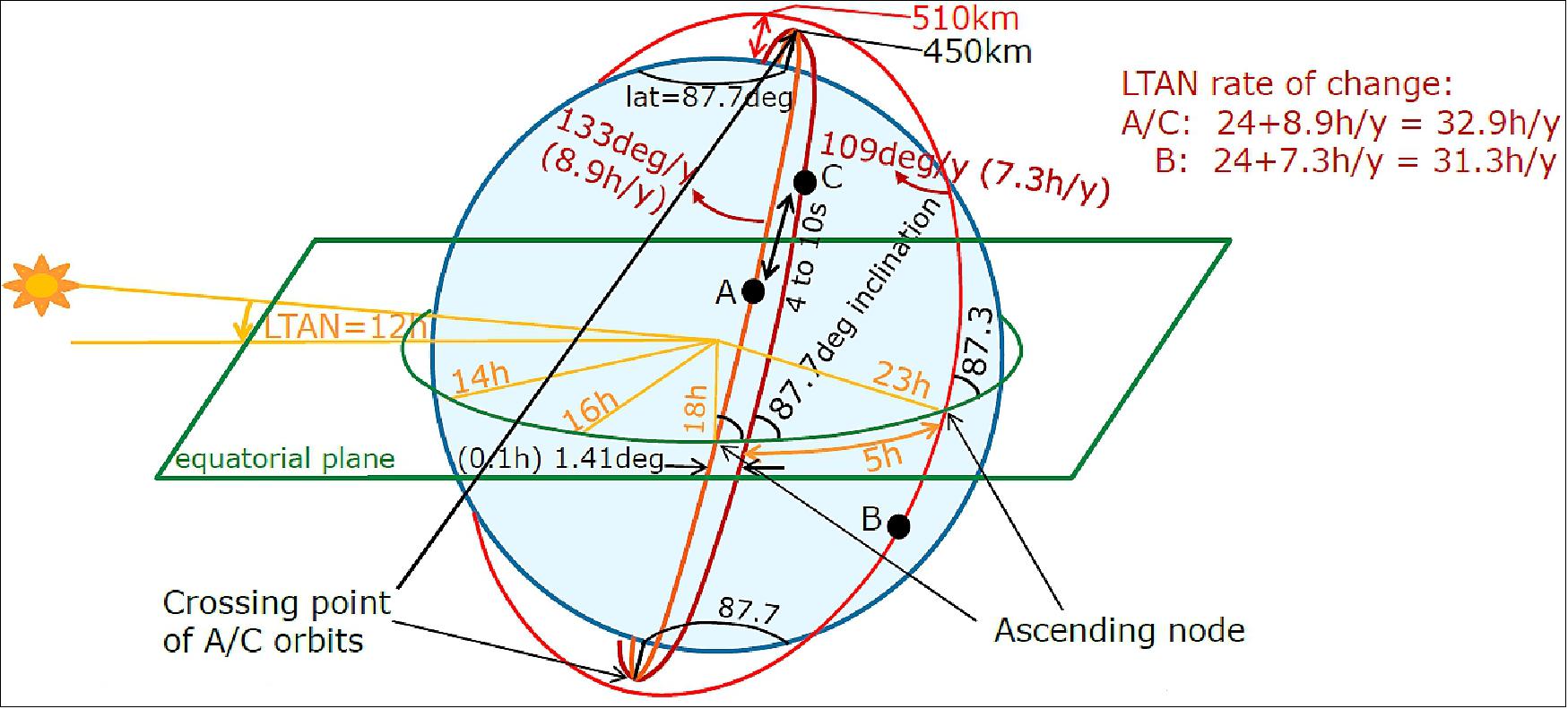

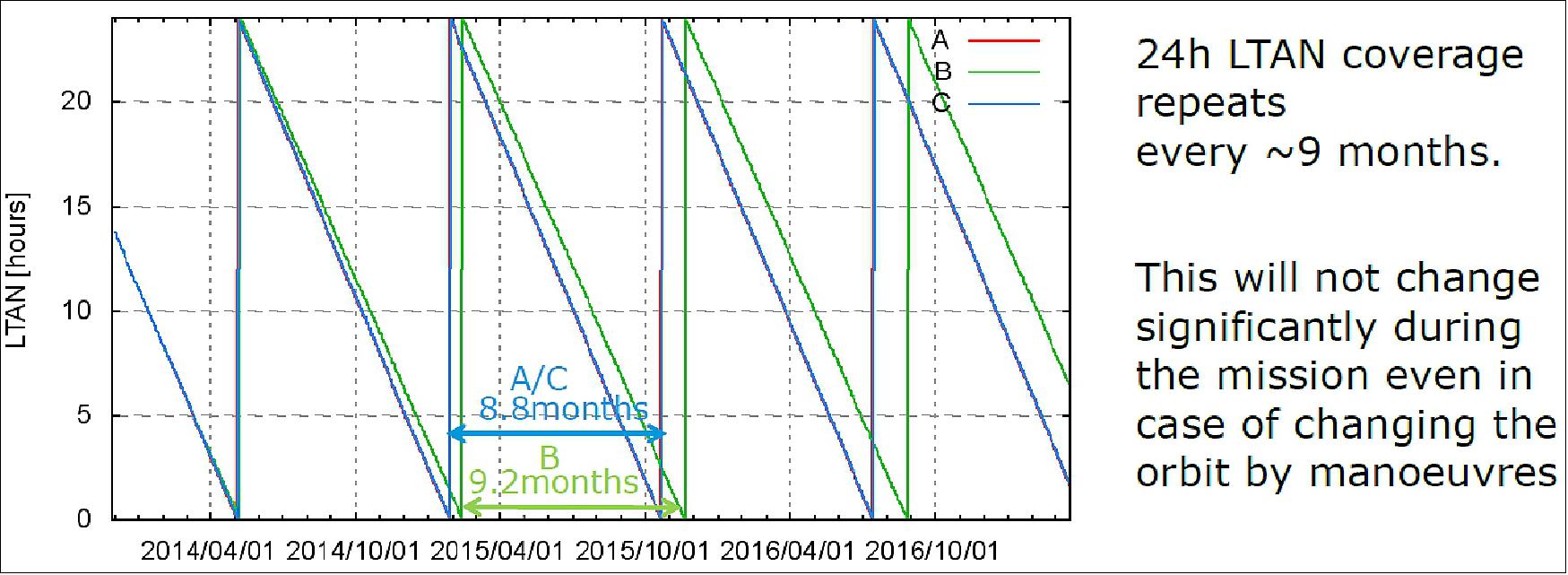

Accurate determination and separation of the large-scale magnetospheric field, which is essential for better separation of core and lithospheric fields, and for induction studies, requires that the orbital planes of the spacecraft are separated by 3 to 9 hours in local time. For improving the resolution of lithospheric magnetization mapping, the satellites should fly at low altitudes - thus experiencing some drag, but commensurate with the goals of a multi-year mission lifetime. The three satellites are being flown in 3 orbital planes with 2 different near-polar inclinations to provide a mutual orbital drift over time (Figure 20 and 21).

• Two satellites (Swarm A+B) are in a similar plane of 87.4º inclination. The satellite pair of 87.4º inclination will fly at a mean altitude of 450 km, their east-west separation shall be 1-1.4º, and the maximal differential delay in orbit shall be about 10 s. The formation-flying aspects concern the satellite pair, a side-by-side formation, requiring some formation maintenance.

• One higher orbit satellite (Swarm C) in a circular orbit with 88º inclination at an initial altitude of 530 km. The right ascension of the ascending node is drifting somewhat slower than the two other satellites, thus building up a difference of 9 hours in local time after 4 years.

Note: Due to ASM instrument problems on Swarm-C (Charlie), it was decided prior to launch to place Charlie with Alpha on the lower orbit, and Bravo on the higher orbit.

Parameter | Swarm-A (Alpha) | Swarm-C (Charlie) | Swarm-B (Bravo) |

Orbital altitude | ≤ 460 km (initial altitude of satellite pair) | ≤ 530 km | |

Orbital inclination | 87.4º | 88º | |

ΔRAAN (Right Ascension of Ascending Node) | 1.4º difference between A and B | ~0-135º difference | |

Mean anomaly at epoch | Δt = 2-10 s difference between A and B | N/A | |

LTAN evolution (Figure 20, right-hand side) | 24 hours of local time coverage every 7-10 months | ||

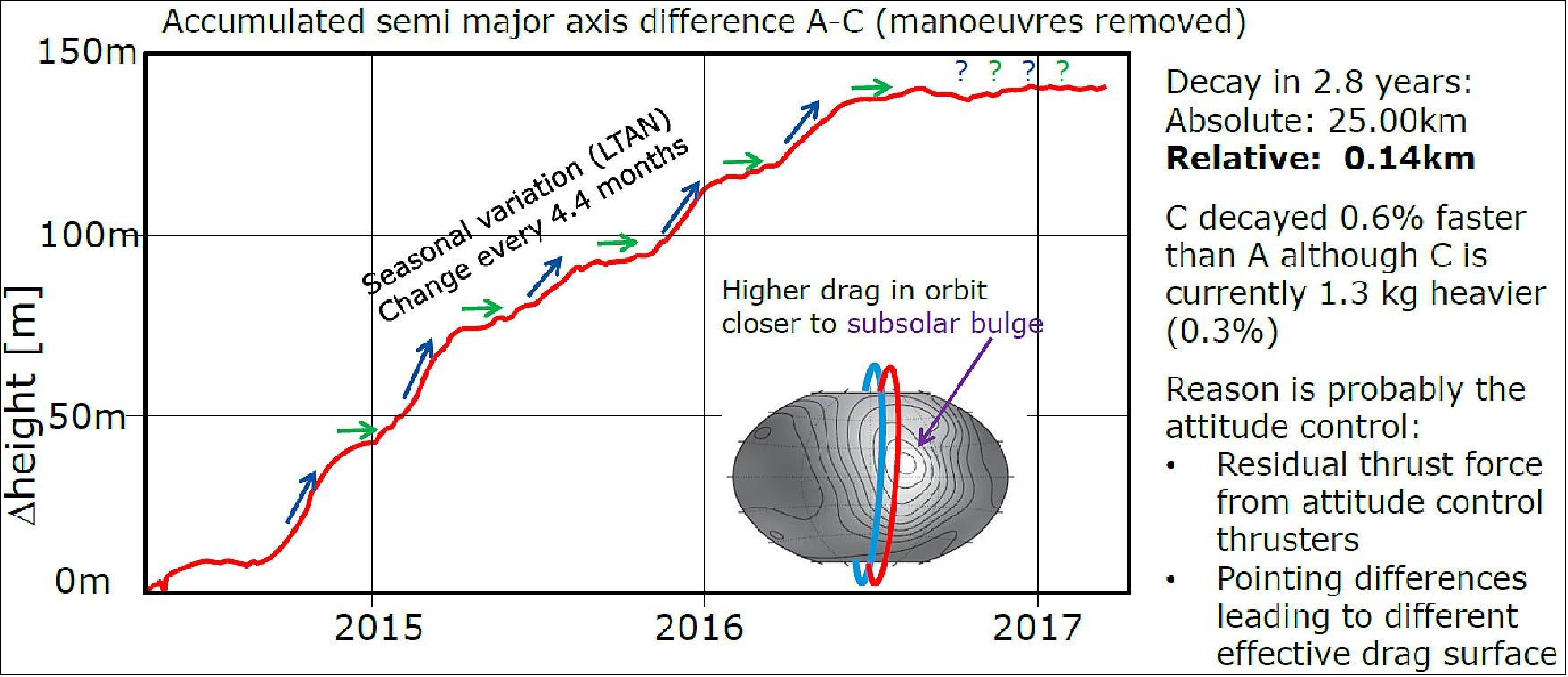

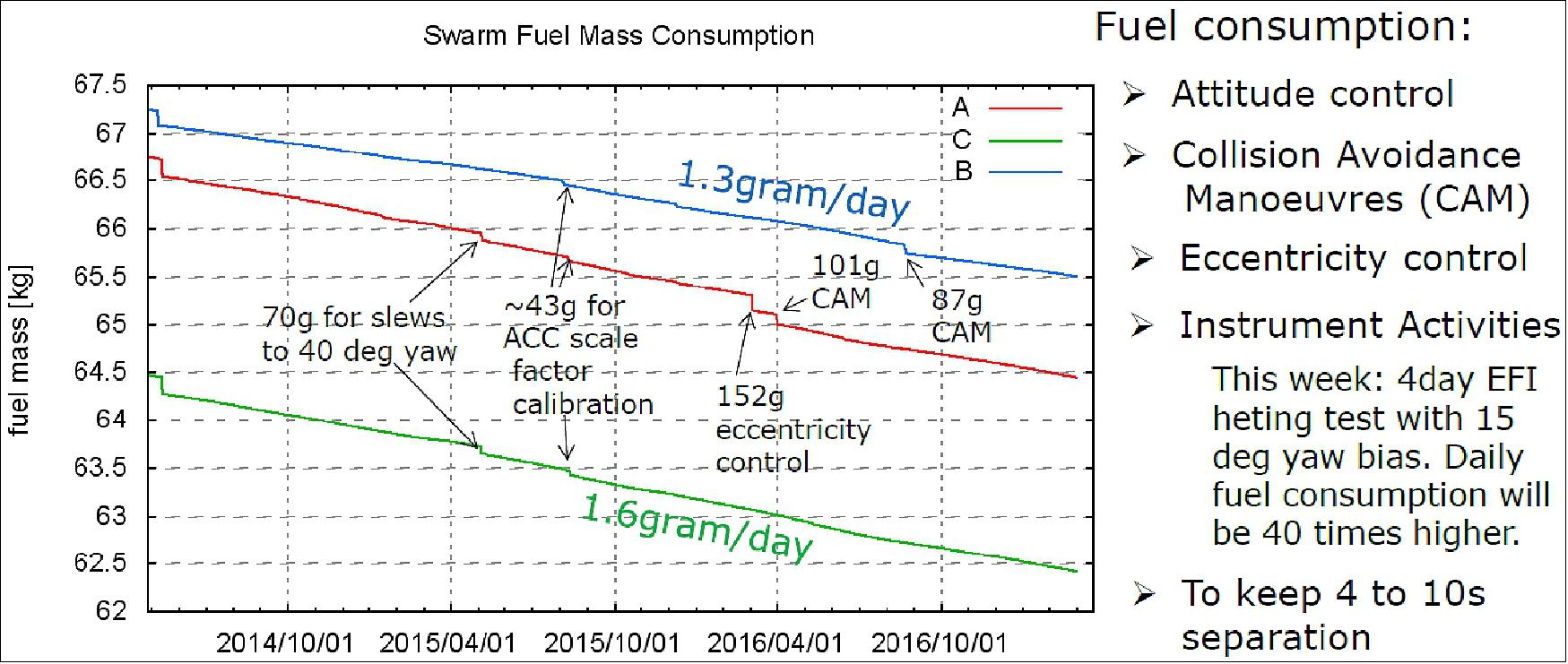

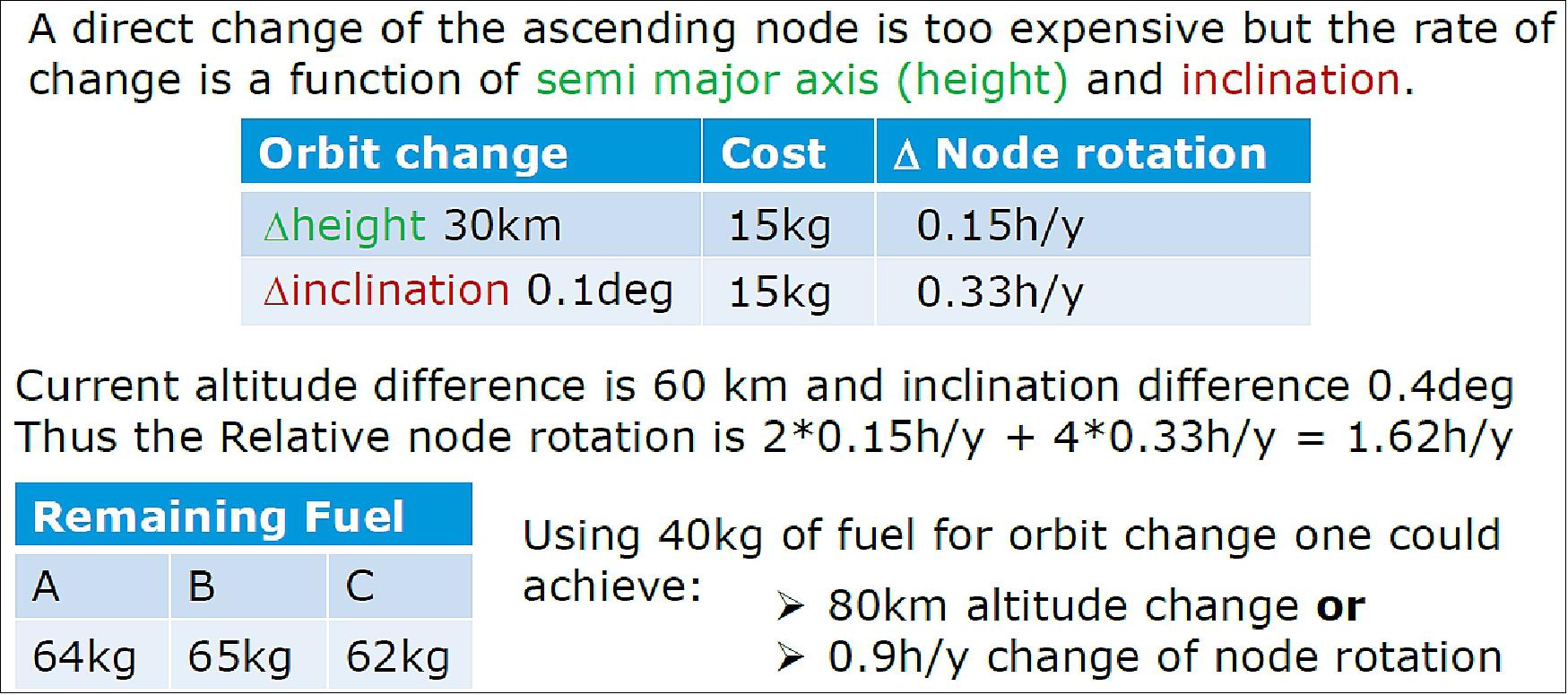

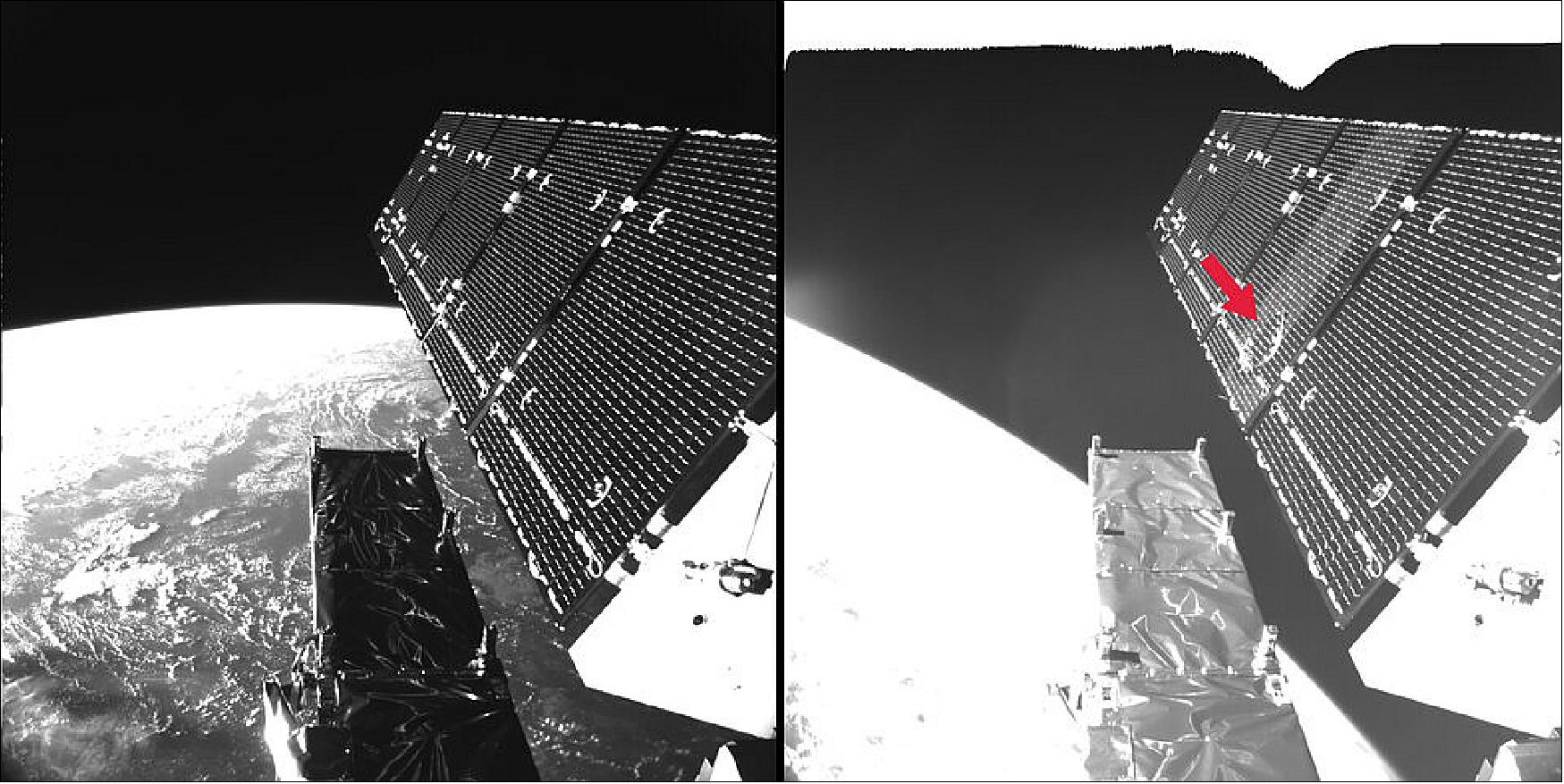

Swarm Mission Orbit Update Information as of March 2017

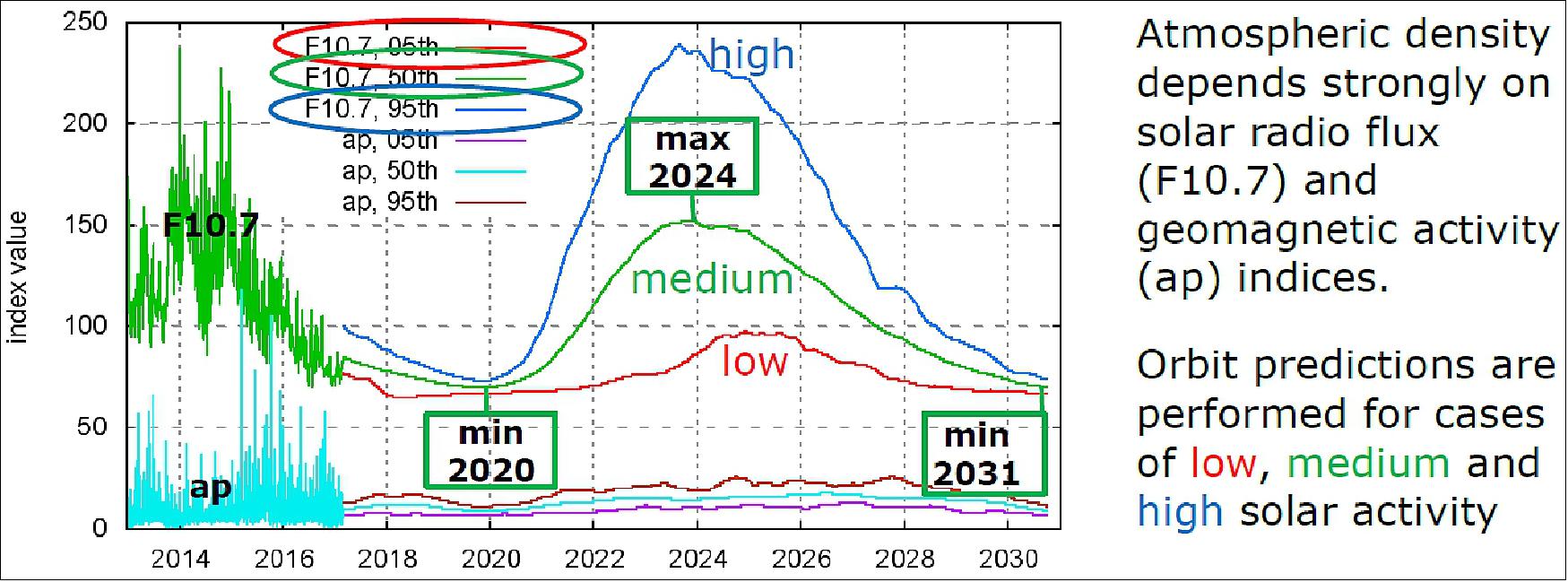

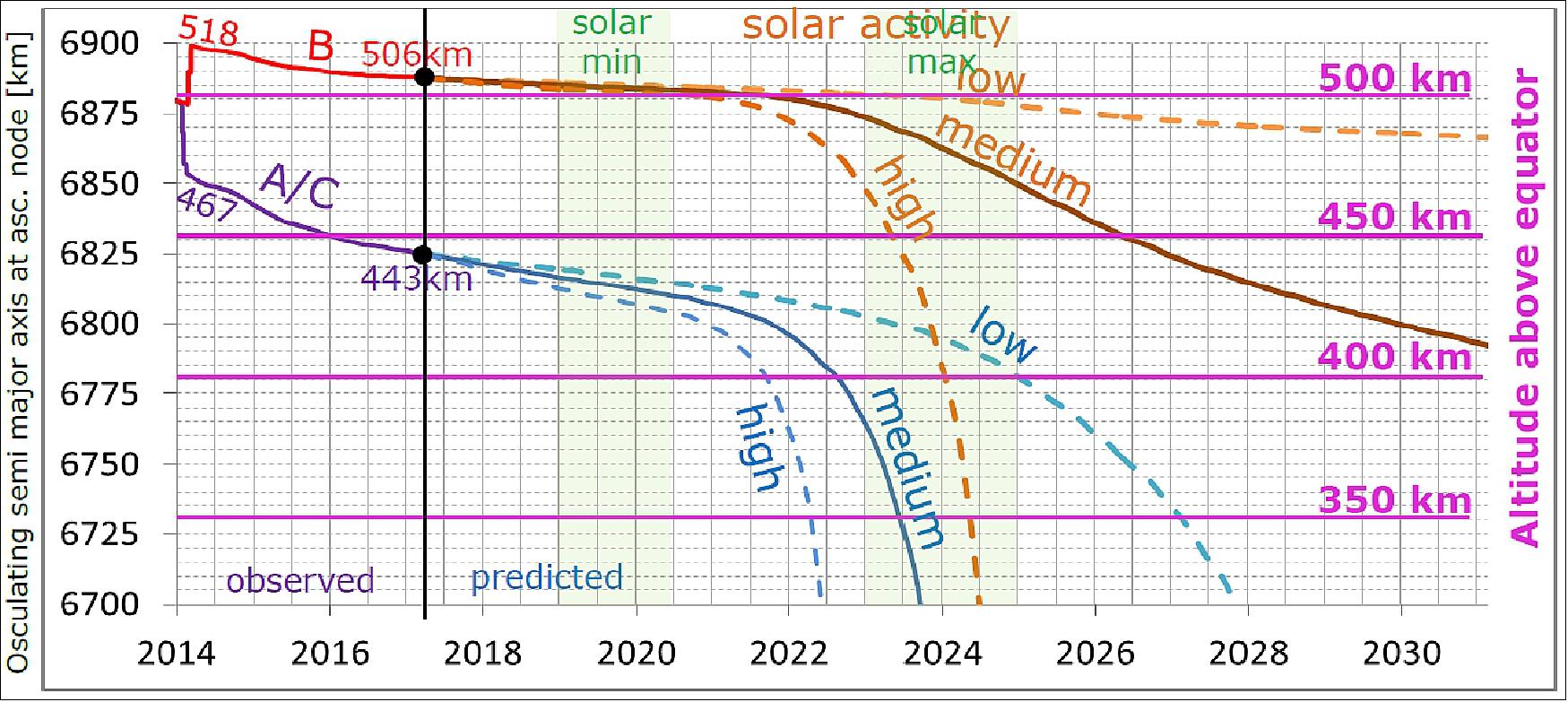

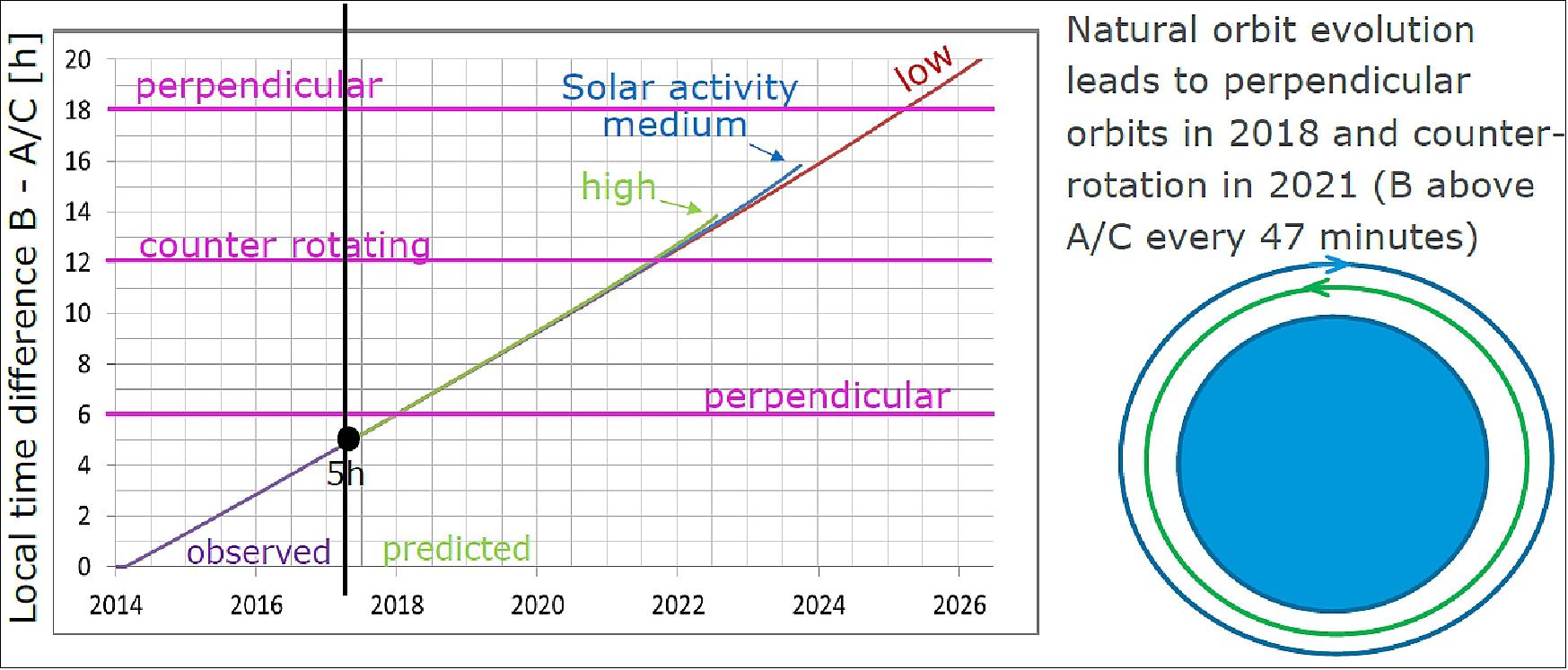

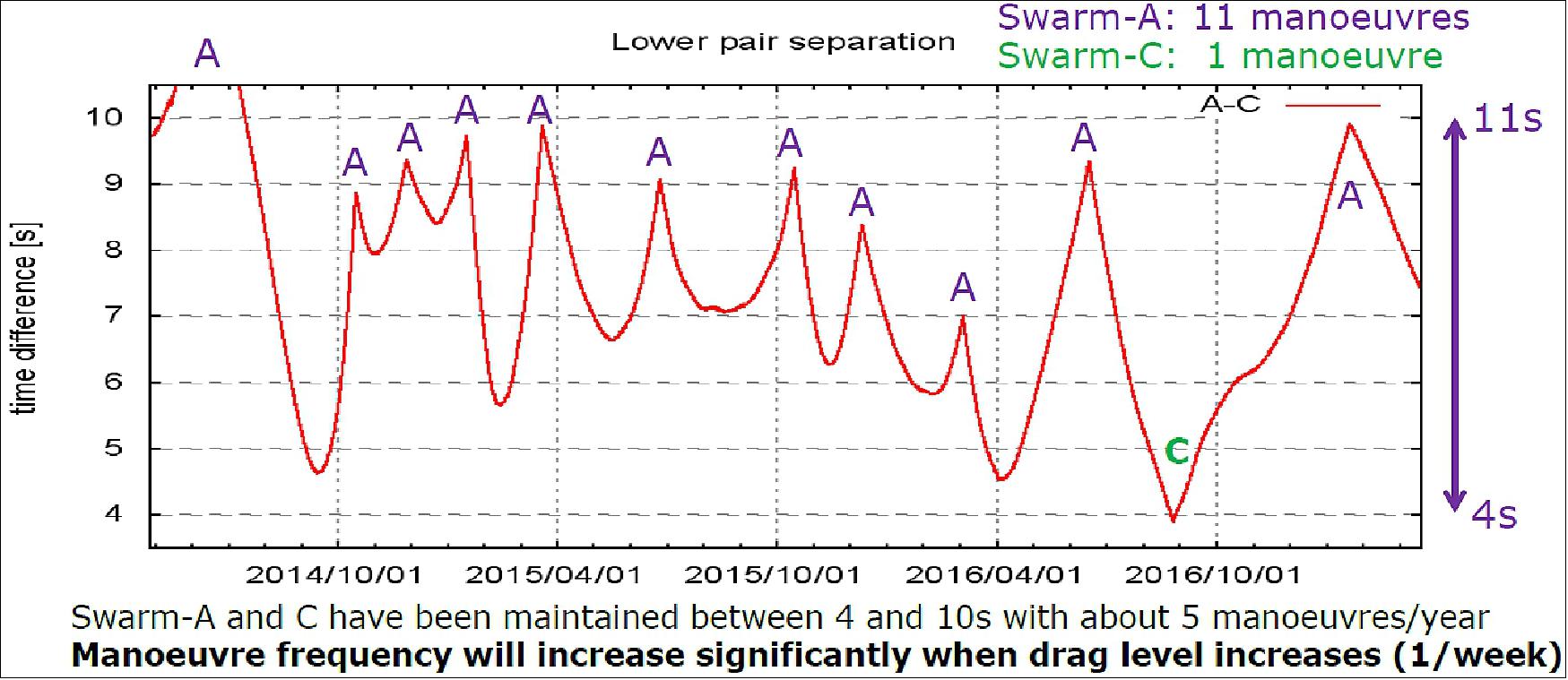

The following 8 Figures (Figure 24 to 32), dealing with the Swarm constellation flight dynamics, were provided by Detlef Sieg of ESA. They were presented at the 4th Swarm Science Meeting & Geodetic Workshop in Banff, Canada. 56)

Mission Status

• July 14, 2022: The pressure is on at ESA’s mission control. An ESA satellite dodges out of the way of a mystery piece of space junk spotted just hours before a potential collision. 57)

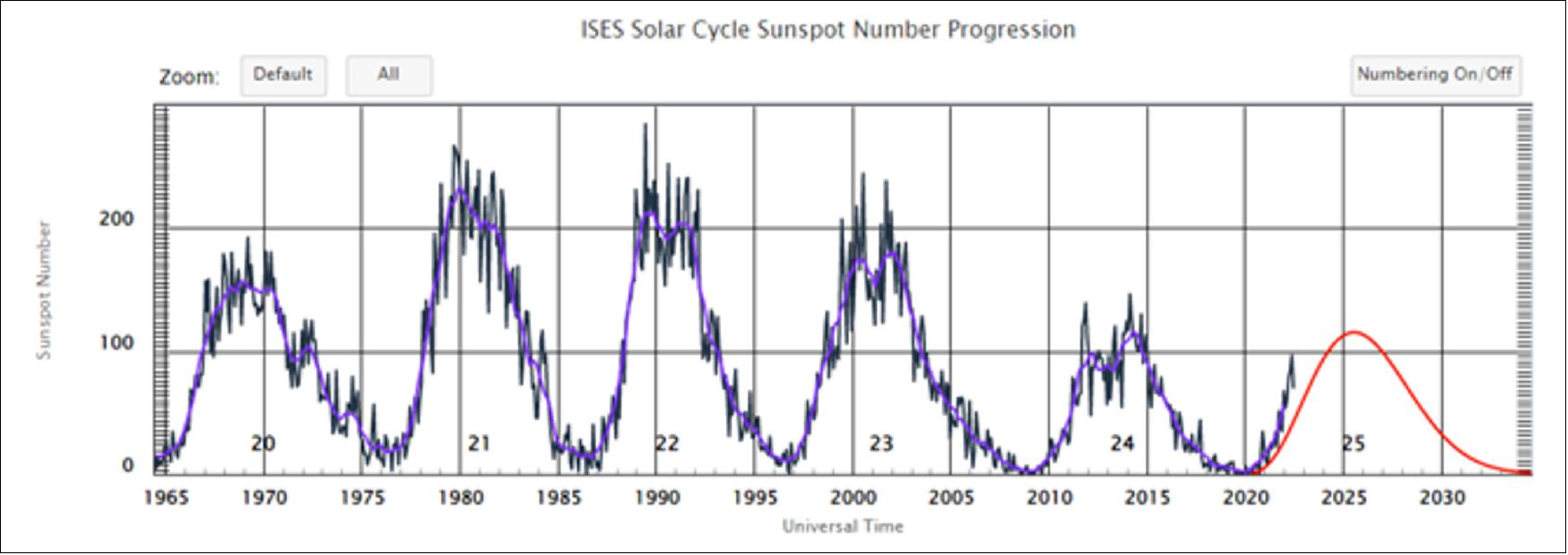

- Now a crucial step in the spacecraft’s ongoing journey to safer skies has to be quickly rescheduled, as violent solar activity related to the ramping up of the solar cycle warps Earth’s atmosphere and threatens to drag it down out of orbit.

A swarm? Of bugs?

- Not quite – Swarm is ESA’s mission to unravel the mysteries of Earth’s magnetic field. It’s made up of three satellites, A, B and C – affectionately known as Alpha, Bravo and Charlie.

What happened?

- A small piece of human-made rubbish circling our planet – known as space debris – was detected hurtling towards Alpha at 16:00 CEST, on 30 June. A potential collision was predicted just eight hours later, shortly after midnight. The risk of impact was high enough that Alpha needed to get out of the way – fast.

There’s rubbish in space?

- A lot of it. Old satellites, rocket parts and small pieces of debris left over from previous collisions and messy breakups. Each little piece can cause serious damage to a satellite, larger ones can destroy a satellite and create large amount of new debris.

Was this the first time this has happened?

- That day? Maybe. Ever? No way. Each one of our satellites has to perform on average two evasive manoeuvres every year – and that’s not including all the alerts we get that don’t end up needing evasive action.

Then what’s the big deal?

- Carrying out evasive action – known as a ‘collision avoidance manoeuvre’ – requires a lot of planning. You have to check that you’re not moving the satellite into a new orbit that puts it at risk of other collisions and you have to calculate how to get back to your original orbit using as little fuel and losing as little science data as possible.

- ESA’s Space Debris Office analyses data from the US Space Surveillance Network and raises the warning of a potential collision to ESA’s Flight Control and Flight Dynamics teams, usually more than 24 hours before the piece of debris comes closest to the satellite.

- In this case, we only got eight hours’ notice.

- And worse, the alert meant that the Swarm team was now suddenly racing against two clocks. Another manoeuvre was planned for just a few hours after the potential collision and had to be cancelled to give Alpha enough time to duck out of the way of the debris. That manoeuvre was also very time sensitive and had to be entirely replanned, recalculated and carried out within a day.

What was the other manoeuvre?

- Alpha and Charlie were climbing to escape the wrath of the Sun. Both satellites needed to carry out 25 manoeuvres over a period of 10 weeks to reach their new higher orbits. One of Alpha’s manoeuvres was planned for just a few hours after the possible collision.

Wait, the Sun is killing satellites?

- Our Sun is entering a very active part of its ‘solar cycle’ right now. This activity is increasing the density of Earth’s upper atmosphere. Satellites are running through ‘thicker’ air, slowing them down and requiring them to use up more limited onboard fuel to stay in orbit. Alpha and Charlie were moving up into a less dense part of the atmosphere where they can stay in orbit and collect science data hopefully for many more years and mission extensions!

What would have happened without this manoeuvre?

- Alpha would have drifted towards Charlie and the orbits of the two satellites would have soon crossed. This would have left the overall Swarm mission ‘cross-eyed’, limiting its ability to do science until another set of manoeuvres realigned Alpha and Charlie.

Is Swarm OK now?

- The Swarm team got to work with a reaction time to rival an Olympic sprinter. Working together with the Flight Dynamics team at ESA’s mission control, they planned and carried out the evasive action in just four hours, and then replanned and carried out the other manoeuvre within 24 hours.

- Alpha is now safe from a collision with that piece of debris and has completed its climb to safer skies alongside Charlie. But there is lots of debris out there, and this shows with how little warning it can threaten a satellite.

How are your teams keeping up with all these collision alerts?

- With new tech and more sustainable behaviour. We’re building new technology to track more debris, developing new computational tools that will help us plan and carry out the rapidly increasing number of evasive manoeuvres, and working on guidelines that limit the amount of new rubbish we and other satellite operators add to the problem. We’re even working on ways to grab larger pieces of debris and remove them from orbit using a ‘space claw’.

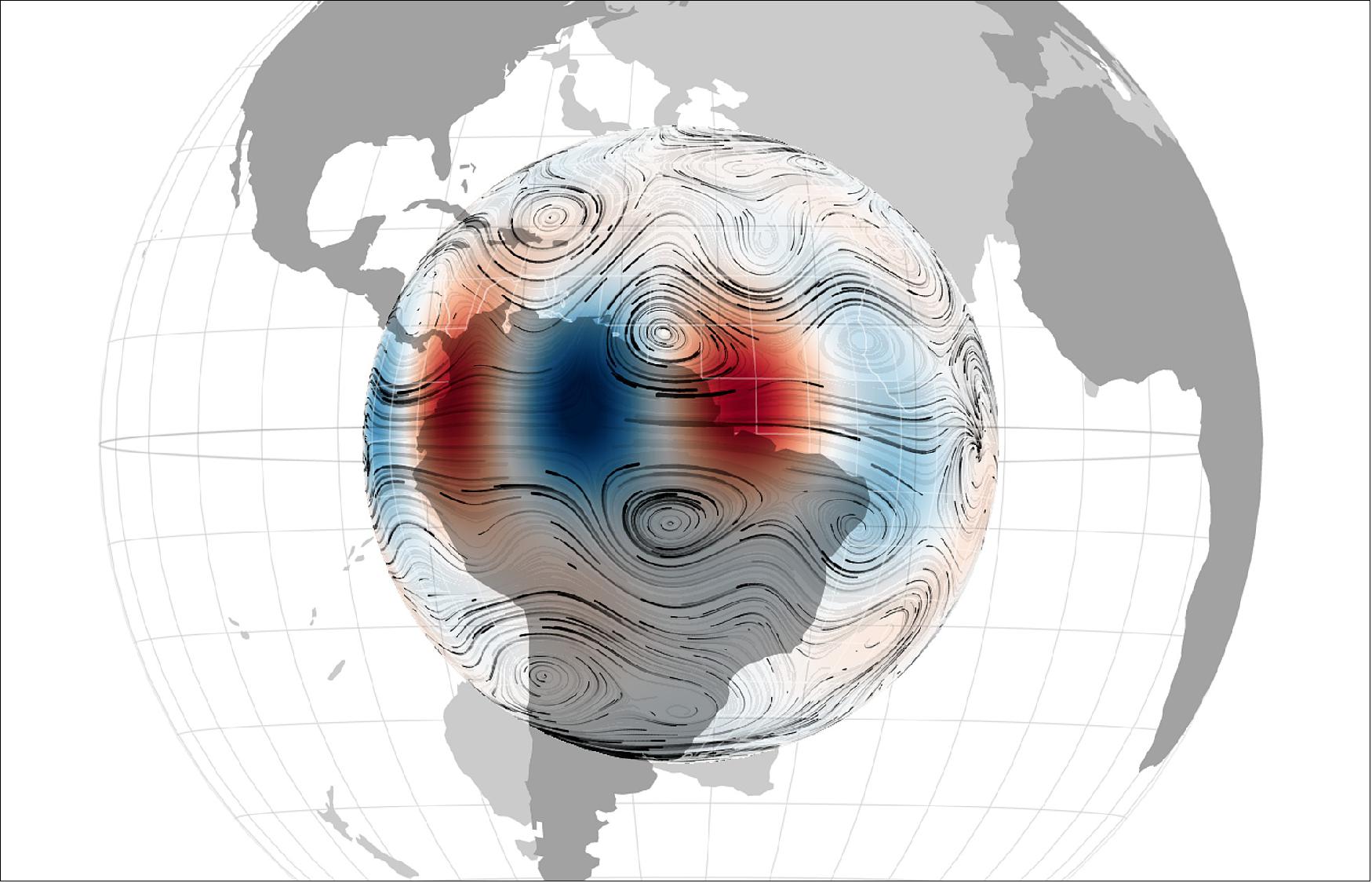

• May 23, 2022: While volcanic eruptions and earthquakes serve as immediate reminders that Earth’s insides are anything but tranquil, there are also other, more elusive, dynamic processes happening deep down below our feet. Using information from ESA’s Swarm satellite mission, scientists have discovered a completely new type of magnetic wave that sweeps across the outermost part of Earth’s outer core every seven years. This fascinating finding, presented today at ESA’s Living Planet Symposium, opens a new window into a world we can never see. 58)

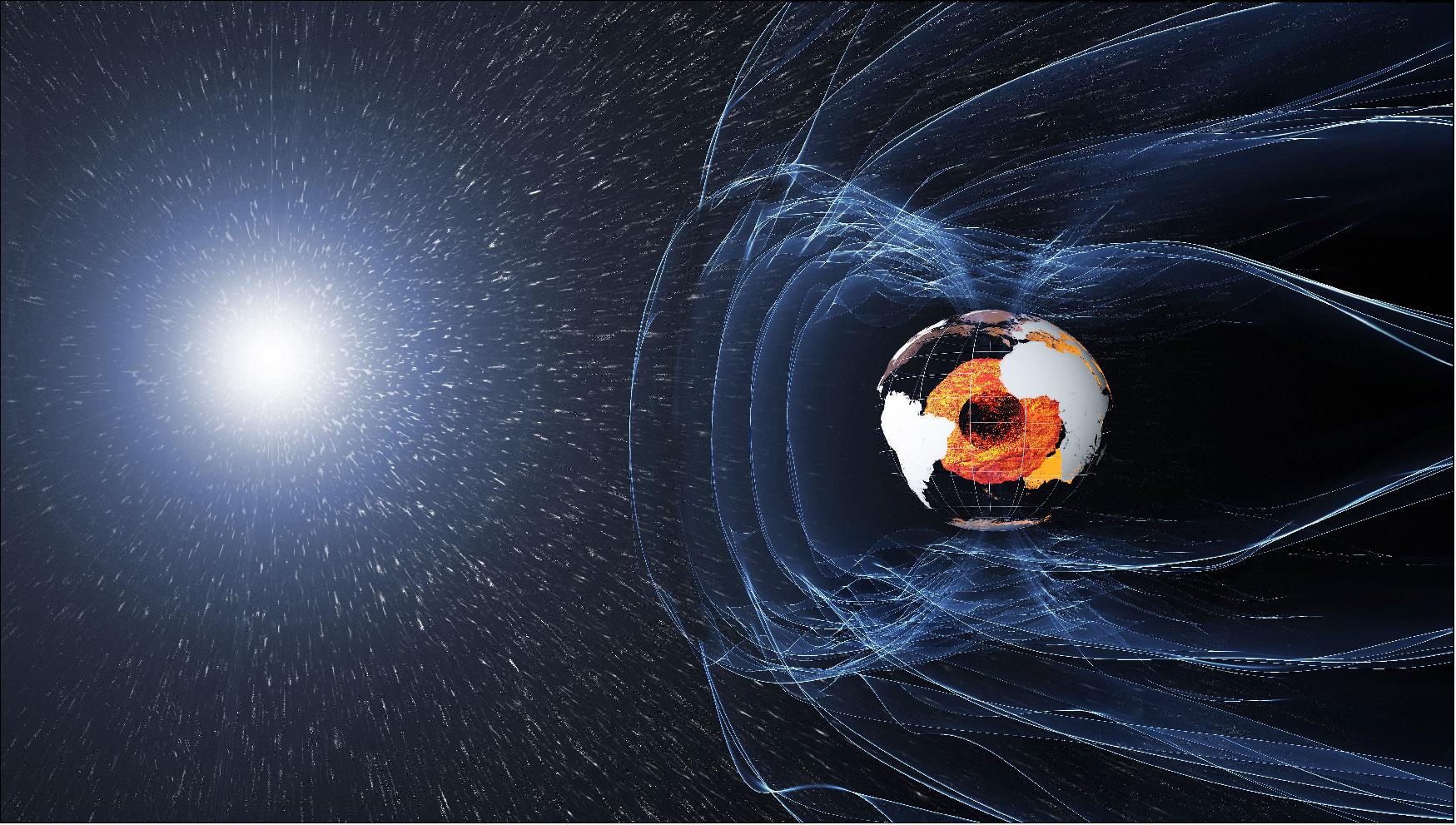

- Earth’s magnetic field is like a huge bubble protecting us from the onslaught of cosmic radiation and charged particles carried by powerful winds that escape the Sun’s gravitational pull and stream across the Solar System. Without our magnetic field, life as we know it would not exist.

- Understanding exactly how and where our magnetic field is generated, why it fluctuates constantly, how it interacts with solar wind and, indeed, why it is currently weakening, is not only of academic interest but also of benefit to society. For example, solar storms can damage communication networks and navigation systems and satellites, so while we can’t do anything about changes in the magnetic field, understanding this invisible force helps to be prepared.

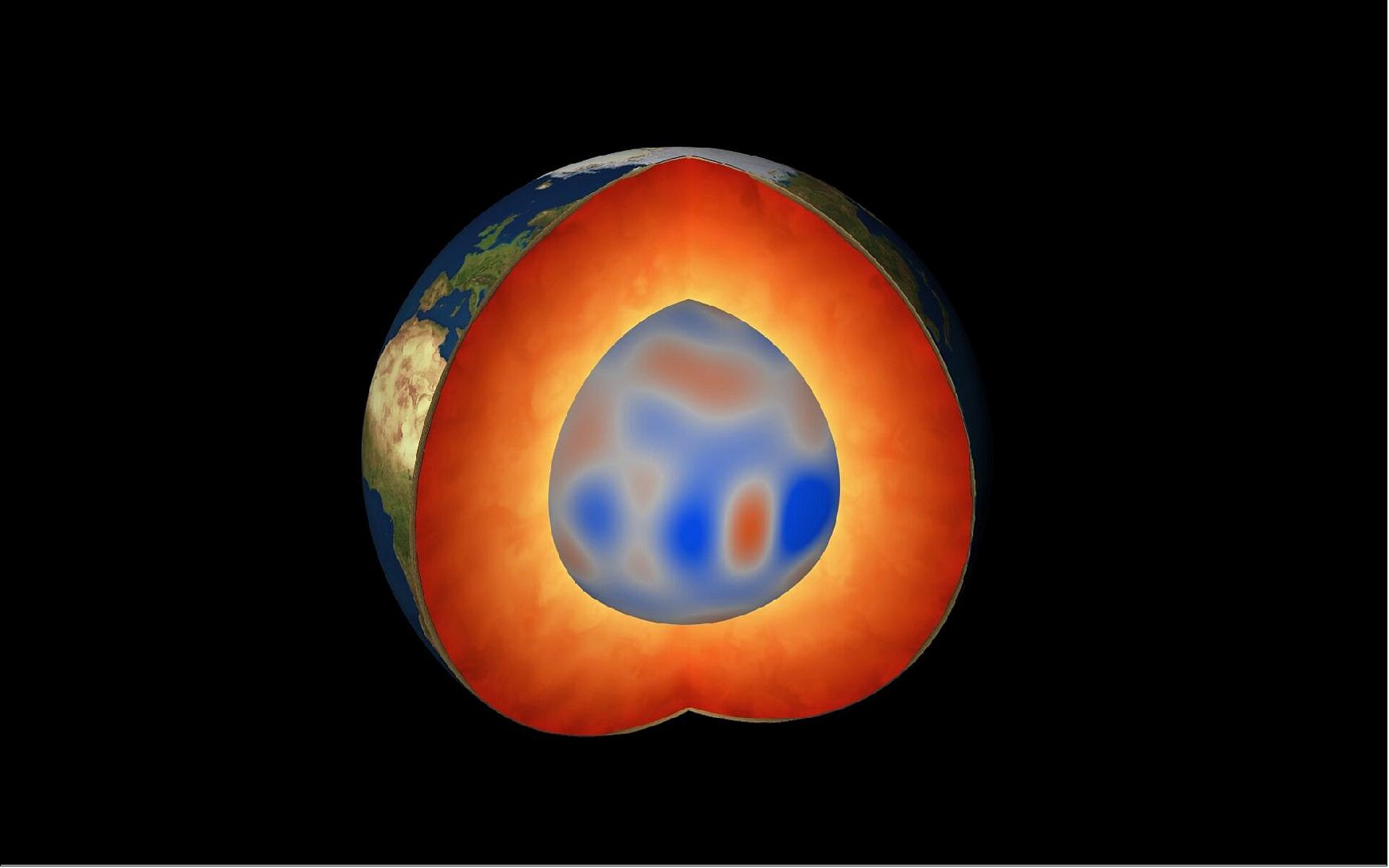

- Most of the field is generated by an ocean of superheated, swirling liquid iron that makes up Earth’s outer core 3000 km under our feet. Acting like the spinning conductor in a bicycle dynamo, it generates electrical currents and the continuously changing electromagnetic field.

- ESA’s Swarm mission, which comprises three identical satellites, measures these magnetic signals that stem from Earth’s core, as well as other signals that come from the crust, oceans, ionosphere and magnetosphere.

- Since the trio of Swarm satellites were launched in 2013, scientists have been analysing their data to gain new insight into many of Earth’s natural processes, from space weather to the physics and dynamics of Earth’s stormy heart.

- Measuring our magnetic field from space is the only real way of probing deep down to Earth’s core. Seismology and mineral physics provide information about the material properties of the core, but they do not shed any light on the dynamo-generating motion of the liquid outer core.

- But now, using data from the Swarm mission, scientists have unearthed a hidden secret.

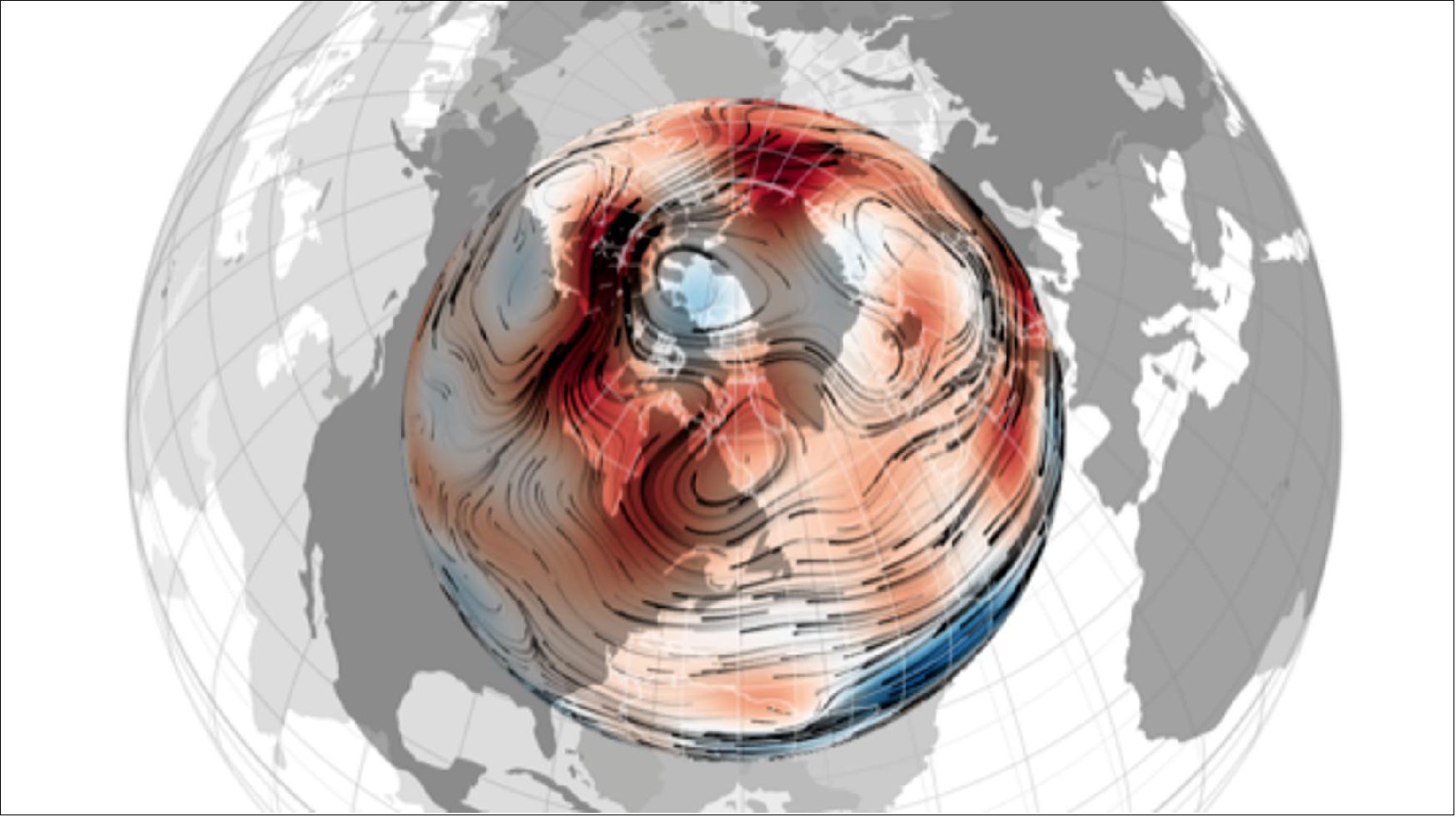

- A paper, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, describes how a team of scientists detected a new type of magnetic wave that sweeps across the ‘surface’ of Earth’s outer core – so where the core meets the mantle. This mysterious wave oscillates every seven years and propagates westward at up to 1500 km a year. 59)

- Nicolas Gillet, from the University Université Grenoble Alpes and lead author of the paper, said, “Geophysicists have long theorised over the existence of such waves, but they were thought to take place over much longer time scales than our research has shown.

- “We combined satellite measurements from Swarm, and also from the earlier German Champ mission and Danish Ørsted mission, with a computer model of the geodynamo to explain what the ground-based data had thrown up – and this led to our discovery.”

- Owing to Earth’s rotation, these waves align in columns along the axis of rotation. The motion and magnetic field changes associated with these waves are strongest near the equatorial region of the core.

- While the research exhibits magneto-Coriolis waves near seven-year period, the question of the existence of such waves that would oscillate at different periods, however, remains.

- Dr Gillet added, “Magnetic waves are likely to be triggered by disturbances deep within the Earth's fluid core, possibly related to buoyancy plumes. Each wave is specified by its period and typical length-scale, and the period depends on characteristics of the forces at play. For magneto-Coriolis waves, the period is indicative of the intensity of the magnetic field within the core.

- “Our research suggests that other such waves are likely to exist, probably with longer periods – but their discovery relies on more research.”

- ESA’s Swarm mission scientist, Ilias Daras, noted, “This current research is certainly going to improve the scientific model of the magnetic field within Earth’s outer core. It may also give us new insight into the electrical conductivity of the lowermost part of the mantle and also of Earth’s thermal history.”

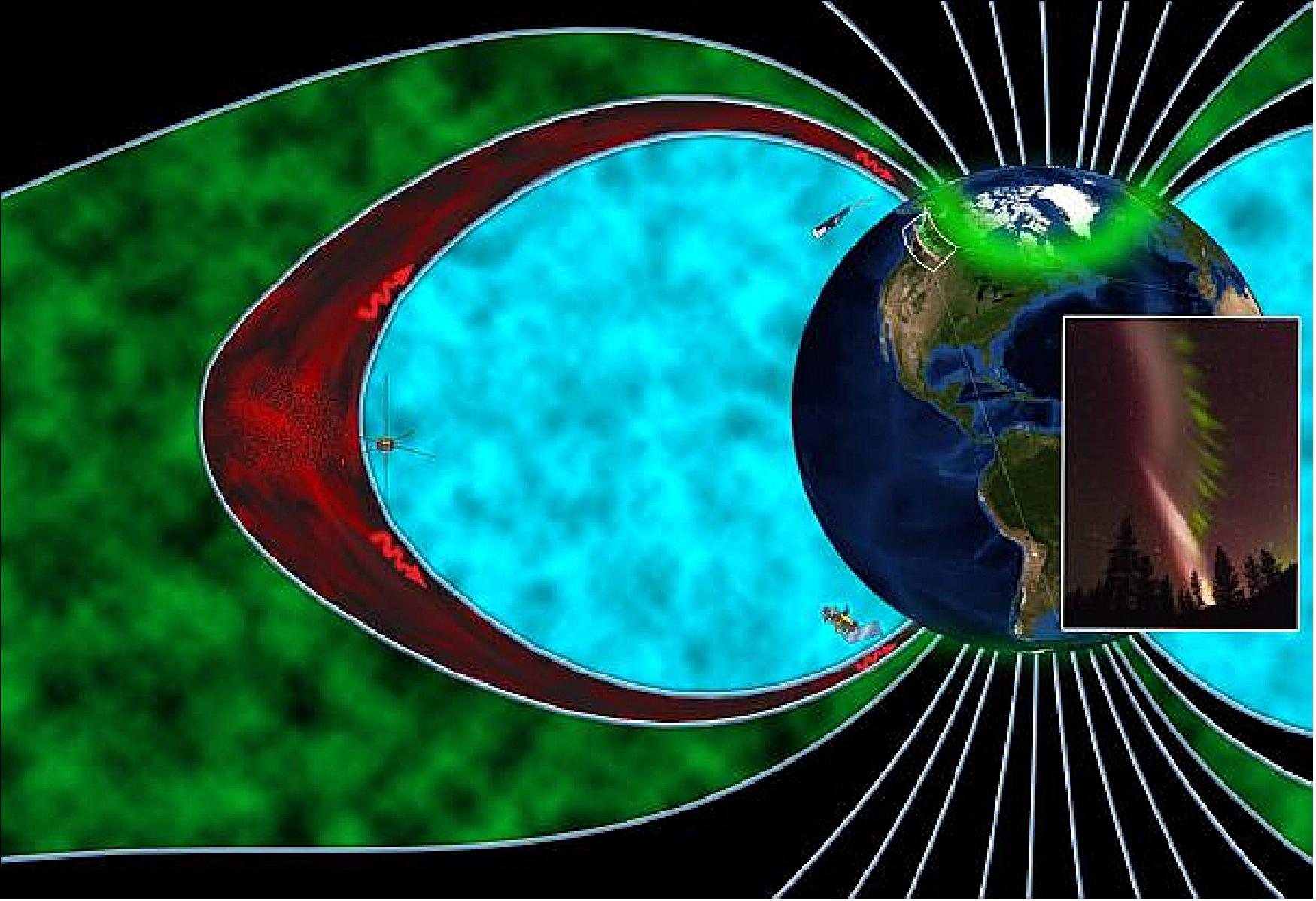

• December 15, 2021: The notion of living in a bubble is usually associated with negative connotations, but all life on Earth is dependent on the safe bubble created by our magnetic field. Understanding how the field is generated, how it protects us and how it sometimes gives way to charged particles from the solar wind is not just a matter of scientific interest, but also a matter of safety. Using information from ESA’s Cluster and Swarm missions along with measurements from the ground, scientists have, for the first time, been able to confirm that curiously named bursty bulk flows are directly connected to abrupt changes in the magnetic field near Earth’s surface, which can cause damage to pipelines and electrical power lines. 60)

- The magnetosphere is a teardrop-shaped region in space that begins some 65,000 km from Earth on the day side and extends to over 6,000,000 km on the night side. It is formed through interactions between Earth’s magnetic field and supersonic wind flowing from the Sun.

- These interactions are extremely dynamic and comprise complicated magnetic field configurations and electric current systems. Certain solar conditions, known as space weather, can play havoc with the magnetosphere by driving highly energetic particles and currents around the system, sometimes disrupting space-based hardware, ground-based communication networks and power systems.

- In an elliptical orbit around Earth, up to 100,000 km away, ESA’s unique four-spacecraft Cluster mission has been revealing the secrets of our magnetic environment since 2000. Remarkably, the mission is still in excellent health and is still enabling new discoveries in the field of heliophysics – the science examining the relationship between the Sun and bodies in the Solar System, in this case, Earth.

- Launched in 2013, ESA’s trio of Swarm satellites orbit much closer to Earth and are used largely to understand how our magnetic field is generated by measuring precisely the magnetic signals that stem from Earth’s core, mantle, crust and oceans, as well as from the ionosphere and magnetosphere. However, Swarm is also leading to new insights into weather in space.

- The complementarity of these two missions, forming part of the ESA Heliophysics Observatory, gives scientists a unique opportunity to dig deep into Earth’s magnetosphere and further understand the risks of space weather.

- In a paper published in Geophysical Research Letters, scientists describe how they used data from both Cluster and Swarm along with measurements from ground-based instruments to examine the connection between solar storms, bursty bulk flows in the inner magnetosphere and perturbations in the ground level magnetic field which drive ‘geomagnetically induced currents’ on and below Earth’s surface. 61)

- The theory was that intense changes in the geomagnetic field driving geomagnetically induced currents are associated with currents flowing along the magnetic field direction, driven by bursty bulk flows, which are fast bursts of ions typically travelling at more than 150 km per second. These field-aligned currents link the ionosphere and magnetosphere and pass through the locations of both the Cluster and Swarm. Until now this theory had not been confirmed.

- Malcolm Dunlop, from the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the UK, explained, “We used the example of a solar storm in 2015 for our research. Data from Cluster allowed us to examine bursty bulk flows – bursts of particles in the magnetotail – which contribute to large-scale convection of material towards Earth during geomagnetically active times, and which are associated with features in the northern lights known as auroral streamers. Data from Swarm showed corresponding large perturbations closer to Earth associated with connecting field-aligned currents from the outer regions containing the flows.

- “Together with other measurements taken from Earth’s surface, we were able to confirm that intense magnetic field perturbations near Earth are connected to the arrival of bursty bulk flows further out in space.”

- ESA’s Swarm mission manager, Anja Strømme, added, “It’s thanks to having both missions extended well beyond their planned lives, and hence are having both missions in orbit simultaneously, that allowed us to realise these findings.”

- While this scientific discovery might appear somewhat academic, there are real benefits for society.

- The Sun bathes our planet with the light and heat to sustain life, but it also bombards us with dangerous charged particles in the solar wind. These charged particles can damage communication networks and navigation systems such as GPS, and satellites – all of which we rely on for services and information in our daily lives.

- As the paper discusses, these storms can affect Earth’s surface and subsurface, leading to power outages, such as the major blackout that Quebec in Canada suffered in 1989.

- With a rapidly growing infrastructure, both on the ground and in space, that supports modern life, there is an increasing need to understand and monitor weather in space to adopt appropriate mitigation strategies.

- Alexi Glover, from ESA’s Space Weather Office, said, “These new results help further our understanding of processes within the magnetosphere which may lead to potentially hazardous space weather conditions. Understanding these phenomena and their potential effects is essential to develop reliable services for end users operating potentially sensitive infrastructure.”

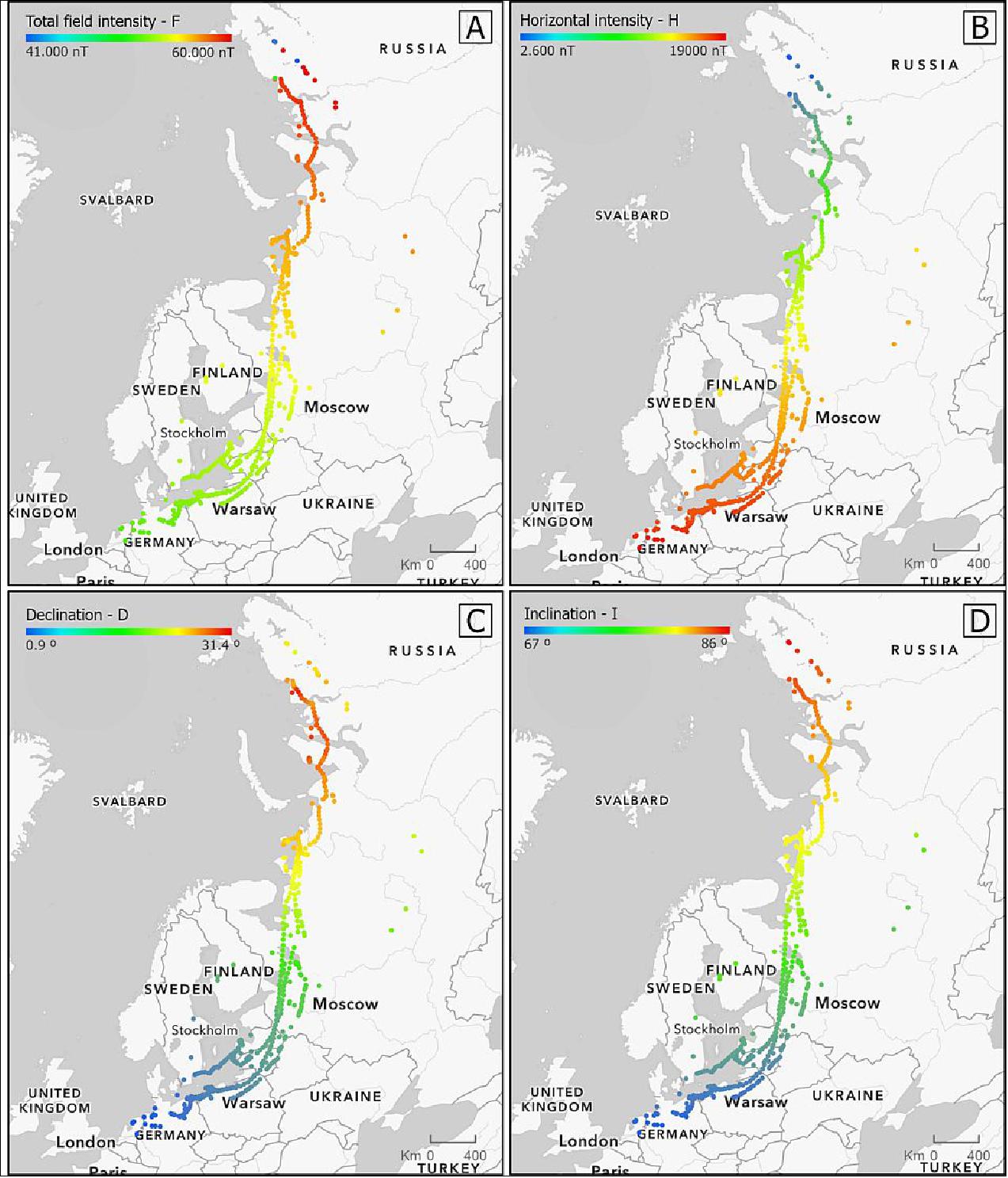

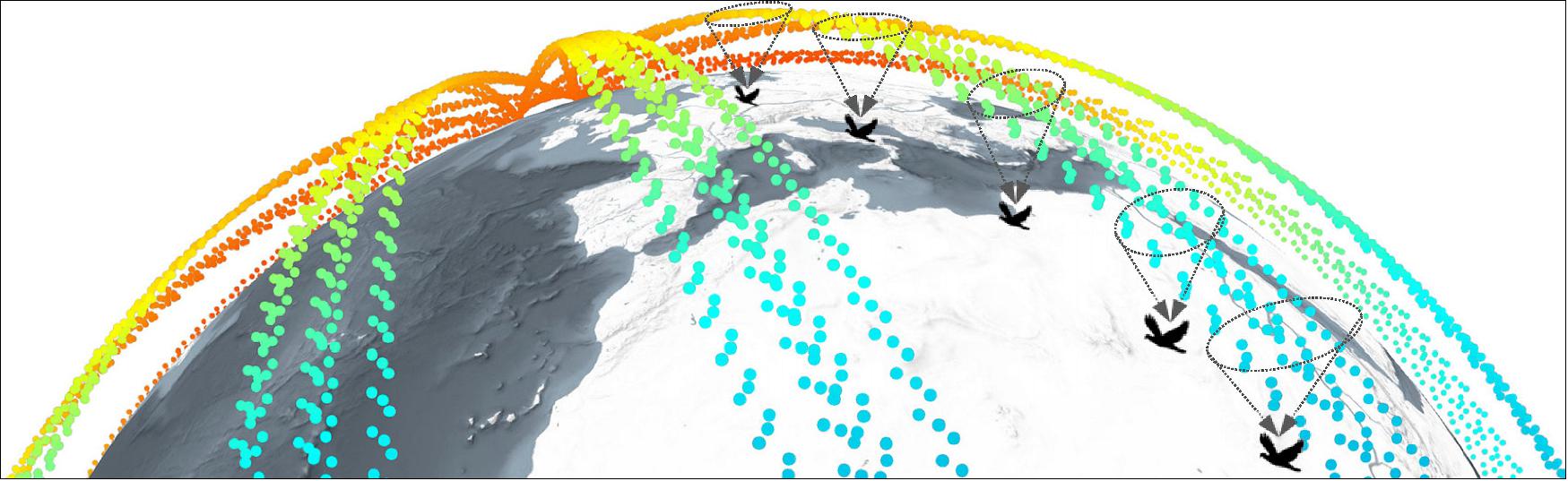

• July 9, 2021: Using measurements from ESA’s Earth Explorer Swarm mission, scientists have developed a new tool that links the strength and direction of the magnetic field to the flight paths of migrating birds. This is a huge step forward to understanding how animals use Earth’s magnetic field to navigate vast distances. 62)

- These days, it is almost unimaginable for us to set off on a long journey without being equipped with some form of satellite navigation, or at least a map. Migratory animals, however, manage to cross entire oceans and continents, navigating with exceptional skills of their own. In spite of decades of research, we still do not understand fully how these remarkable animals are able to find their way – although it has been suspected that Earth’s magnetic field lines are among the cues that guide them.

- Recent advances in GPS and the miniaturization of tracking devices have allowed ecologists to tag migratory animals, from birds to whales, to understand how they travel from A to B. However, while animal tracking data are now common, little investigation has been made into how animals respond to real geomagnetic conditions, since the magnetic field changes continuously across the globe, particularly during geomagnetic storms.

- Until recently, there was no way to assess accurately the strength of the magnetic field at the time and location that animals pass by, which would allow ecologists to study how they use this natural force for navigation.

- However, a new tool allows ecologists, for the first time, to compute the strength and direction of the magnetic field along animal migratory paths.

- Developed by spatial data scientists from the University of St Andrews in Scotland in collaboration with researchers from the British Geological Survey and Canada’s University of Western Ontario, the new tool combines data from ESA’s Swarm magnetic field mission with data stored in Movebank. Movebank is a free database of millions of locations and times of birds and mammals, such as bats and whales, on the move.

- The research, which has been published recently in Movement Ecology, explains how the values were computed and gives examples applied to greater white-fronted geese, which fly from Siberia to Germany on their autumn migration. 63)

- Developed by spatial data scientists from the University of St Andrews in Scotland in collaboration with researchers from the British Geological Survey and Canada’s University of Western Ontario, the new tool combines data from ESA’s Swarm magnetic field mission with data stored in Movebank. Movebank is a free database of millions of locations and times of birds and mammals, such as bats and whales, on the move.

- Urška Demšar, from the University of St Andrews, explains, “We used the time and GPS locations of the animal to find the nearest Swarm data. This then let us compute the expected magnetic field at the animal’s location due to the magnetic field generated by Earth’s core, and accounted for local influence from the geology and the instantaneous effect of the ionosphere and magnetosphere.

- “These contributions were summed and appended to the GPS data, including Swarm measurements from the nearest satellite flyovers for each GPS location. This gives us the best possible estimate of the magnetic field at the animal’s location.”

- This new research means that the study of animal movement can now combine tracking data with geophysical information and lead to new insights on migration behavior.

- This is demonstrated in the Movement Ecology paper by a small biological example, which shows that during geomagnetic storms, the geese were affected and generally veered away from the straight migratory direction towards the North. This is just a small example that cannot yet be generalized, but it shows the possibilities that are now open for study of animal migration with contemporaneous real magnetic data.

- Without the availability of Swarm data, models and the supporting software (viresclient), it would not have been possible to create such an easy-to-use tool for analysis.

- “This is the first direct use of Swarm data in ecology and so represents an exciting new avenue of research between geophysicists, spatial data scientists and ecologists,” notes Ciarán Beggan from the British Geological Survey.

- Dr Demšar emphasizes that, “Adding in a new set of magnetic data will allow us to explore how animals migrate using a whole new set of environmental parameters that was unavailable before Swarm.”

• May 18, 2021: We are all familiar with the bolts of lightning that accompany heavy storms. While these flashes originate in storm clouds and strike downwards, a much more elusive type forms higher up in the atmosphere and shoots up towards space. So, what are the chances of somebody taking photographs of these rarely seen, brief ‘transient luminous events’ at the exact same time as a satellite orbits directly above with the event leaving its signature in the satellite’s data? 64)

- The likelihood of this happening might seem pretty remote, but, remarkably, an observer for the Czech Institute of Atmospheric Physics who is also an avid ‘lightning hunter’ has taken photographs of these transient luminous events that not only coincide with measurements taken by ESA’s Swarm satellite mission, but also with recordings taken from the ground.

- This extraordinary three-way coincidence is leading to better insight into how this type of lightning propagates into space. In addition, these new findings could potentially improve scientific models of the ionized part of Earth’s upper atmosphere – the ionosphere.

- Transient luminous events are optical phenomena that occur high up in the atmosphere and they are linked to electrical activity in underlying thunderstorms. They are very brief, lasting from less than a millisecond to two seconds, and rarely seen from the ground. They are usually only captured by sensitive photographic equipment and, because they emit weak light, photographs can only be taken at night.

- There are several different types of transient luminous events such as sprites, jets and elves, each with their own characteristics.

- Sprites, for example are large electrical discharges that occur at an altitude of around 50–90 km, above large thunderstorm systems. They appear as large, but weak flashes of red and usually happen at the same time as the cloud-to-ground lightning we all know.

- Scientists have long been interested in understanding if lightning propagating to higher in the ionosphere can cause fluctuations in Earth’s magnetic field. The ionosphere is very active part of the atmosphere, responding to the energy it absorbs from the Sun. Gases in the ionosphere are excited by solar radiation to form ions, which have an electrical charge.

- Ewa Slominska, from a small company cooperating with Poland’s Space Research Centre, explained, “Lightning can generate ultralow frequency fluctuations that leak into the upper ionosphere. This means that some lightning bolts are so powerful that they trigger disturbances in Earth's magnetic field and propagate hundreds of kilometers upwards from the thunderstorm, reaching the altitude of Swarm’s orbit.

- “Although Swarm’s main goal is to measure slow changes in the magnetic field, it is apparent that the mission can also detect fast fluctuations in the field. However, Swarm can only do this if one of the satellites is in close proximity to the active thunderstorm and if the lightning is strong enough.”

- Janusz Mlynarczyk, from AGH University of Science and Technology in Krakow, added, “Using the three stations of the WERA system, we are able to locate powerful atmospheric discharges that occur anywhere on Earth and reconstruct their most important physical parameters. This is possible because of a very low attenuation of Extremely Low Frequency (ELF) electromagnetic waves that these discharges generate.

- “Powerful ELF waves can even propagate around the world a few times and still be visible in our recordings. Such powerful sources include sprite-associated discharges. The accumulated electrostatic energy released and observed by Swarm was close to 120 GJ, which is equivalent to the energy released in the detonation of 29 tons of TNT.

- “Although we know that every lightning strike carries a lot of energy, it is clear that this class of lightning is much more powerful. A single bolt of ordinary lightning, which is invisible to Swarm’s instruments, carries enough energy to charge 20 electric cars, but the energy produced by a transient luminous event would be enough to charge more than 800 vehicles.”

- A remarkable aspect to all of this is that one of the scientific team members, Martin Popek, is passionate about capturing sprites, jets and elves on camera. His photographs are proving a very valuable to the team’s research as they have coincided with measurements taken by Swarm and by the ground array.

- ESA’s Swarm mission scientist, Roger Haagmans, commented, “It’s astonishing that Martin manages to capture such fleeting events on camera, but what’s really remarkable is that his dedication to this kind of photography has coincided with measurements from our Swarm mission. His photos add another dimension to the research and we are certainly reaping the benefits of his commitment to hanging outside in the cold and dark!”

• March 9, 2021: For the first time, an international team of scientists has used magnetic data from ESA’s Swarm satellite mission together with aeromagnetic data to help reveal the mysteries of the geology hidden beneath Antarctica’s kilometers-thick ice sheets, and link Antarctica better to its former neighbors. 66)

- Not only is Antarctic sub-ice geology important to understand global supercontinent cycles over billions of years that have shaped Earth’s evolution, it is also pivotal to comprehend how the solid Earth itself influences the Antarctic ice sheet above it.

- The research team from Germany’s Kiel University, the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and National Institute of Oceanography and Applied Geophysics, and Witwatersrand University in South Africa has today published their findings in the Nature journal Scientific Reports. 67)

- Their new study shows that combining satellite and aeromagnetic data provides a key missing link to connect Antarctica’s hidden geology with formerly adjacent continents, namely Australia, India and South Africa – keystones of Gondwana.

- The fact that Antarctica is about as remote as you can get and the land below is covered by a massive ice sheet, makes collecting geophysical information both challenging and expensive. Fortunately, satellites orbiting above can see where humans cannot.

- Thanks to magnetic data from the Swarm mission along with airborne measurements, scientists are paving the way towards understanding Earth’s least accessible continent. This new research links Antarctica to its ancient neighbors with which it has shared a long tectonic history – and that needs piecing together like a jigsaw puzzle.

- The team processed aeromagnetic data from aircraft from over southern Africa, Australia and Antarctica in a consistent manner with the help of Swarm satellite magnetic data.

- Aeromagnetic data do not cover everywhere on Earth, so magnetic models complied from Swarm data help to fill the blanks, especially over India were aeromagnetic data are still not widely available. Furthermore, satellite data help to homogenize the airborne data, which were acquired over a period of more than 60 years with varying accuracy and resolution.

- Jörg Ebbing, from Kiel University, explains, “With the available data, we only had pieces of the puzzle. Only when we put them together with satellite magnetic data, can we see the full picture.”

- The resulting combined datasets provide a new tool for the international scientific community to study the cryptic sub-ice geology of Antarctica, including its influence on the overlying ice sheets.

- Gondwana was an amalgam of continents that incorporated South America, Africa, Arabia, Madagascar, India, Australia, New Zealand and Antarctica. As the tectonic plates collided in the Precambrian and early Cambrian times some 600–500 million years ago, they built huge mountain ranges comparable to the modern Himalayas and Alps. This supercontinent started to breakup in the early Jurassic, about 180 million years ago, ultimately leaving Antarctica stranded and isolated at the South Pole, and covered in ice for around 34 million years.

- “Using the new magnetic data, our animation illustrates how the tectonic plates have moved over millions of years after the breakup of Gondwana,” explains Peter Haas, PhD student at Kiel University.

- Fausto Ferraccioli, Director of Geophysics at the National Institute of Oceanography and Applied Geophysics in Italy, and also affiliated with the British Antarctic Survey, said, “We have been trying to piece together the connections between Antarctica and other continents for decades. We knew that magnetic data play a pivotal role because one can peer beneath the thick Antarctic ice sheet to help extrapolate the geology exposed along the coast into the continent interior.

- “But now we can do much better. With the satellite and aeromagnetic data combined, we can look down deeper into the crust. Together with tectonic plate reconstructions, we can start building tantalizing new magnetic views of the crust to help connect geological and geophysical studies in widely separated continents. Ancient cratons and orogens in Africa, India, Australia and East Antarctica are now better connected magnetically than ever before.”

- ESA’s Roger Haagmans, said, “This research has been carried out within ESA’s Science for Society 3D Earth study where we are using gravity data from the GOCE mission and magnetic data from the Swam mission to understand the structure and dynamic processes deep within Earth. In this instance, Swarm’s magnetic data have played a starring role.”

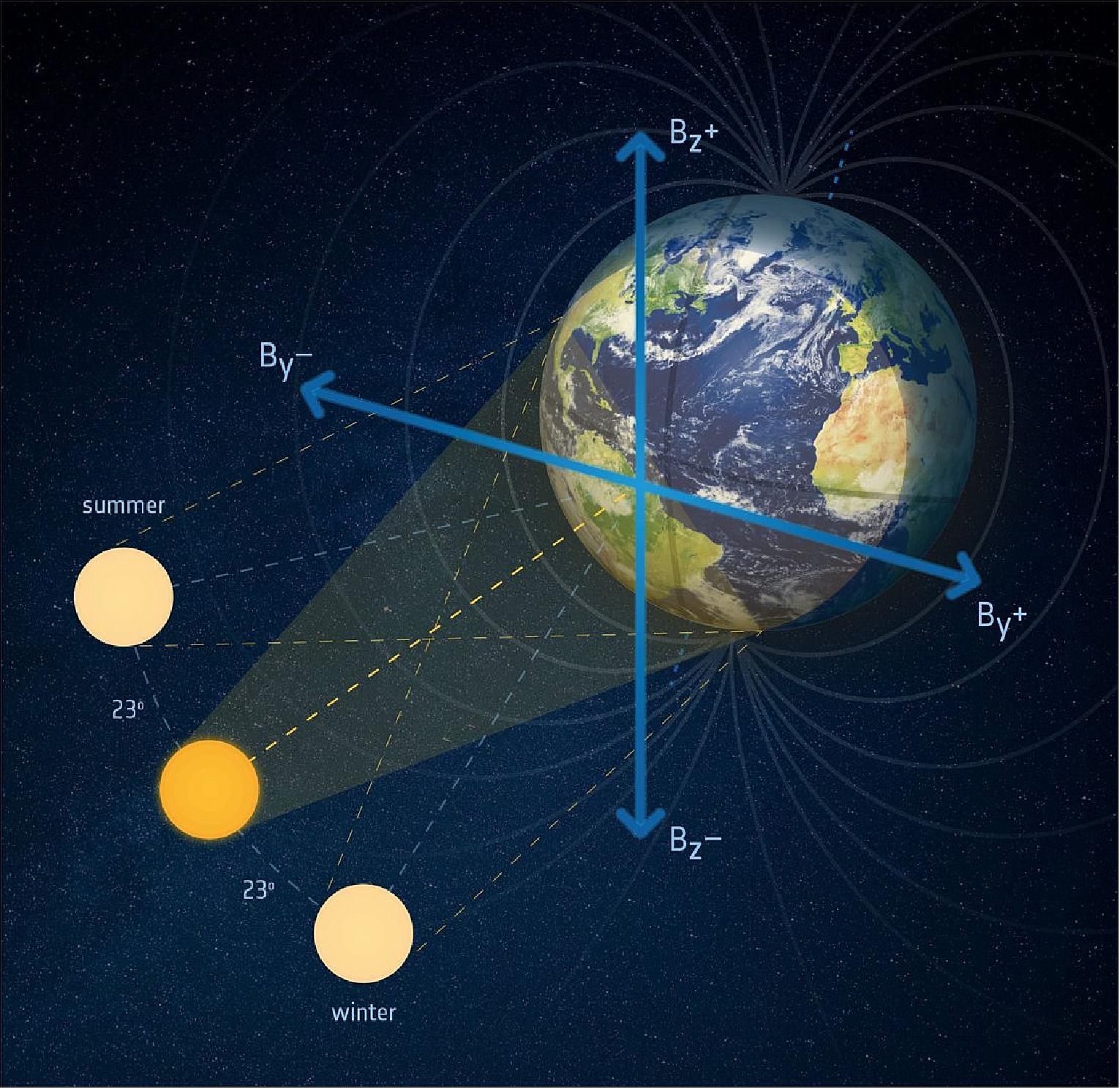

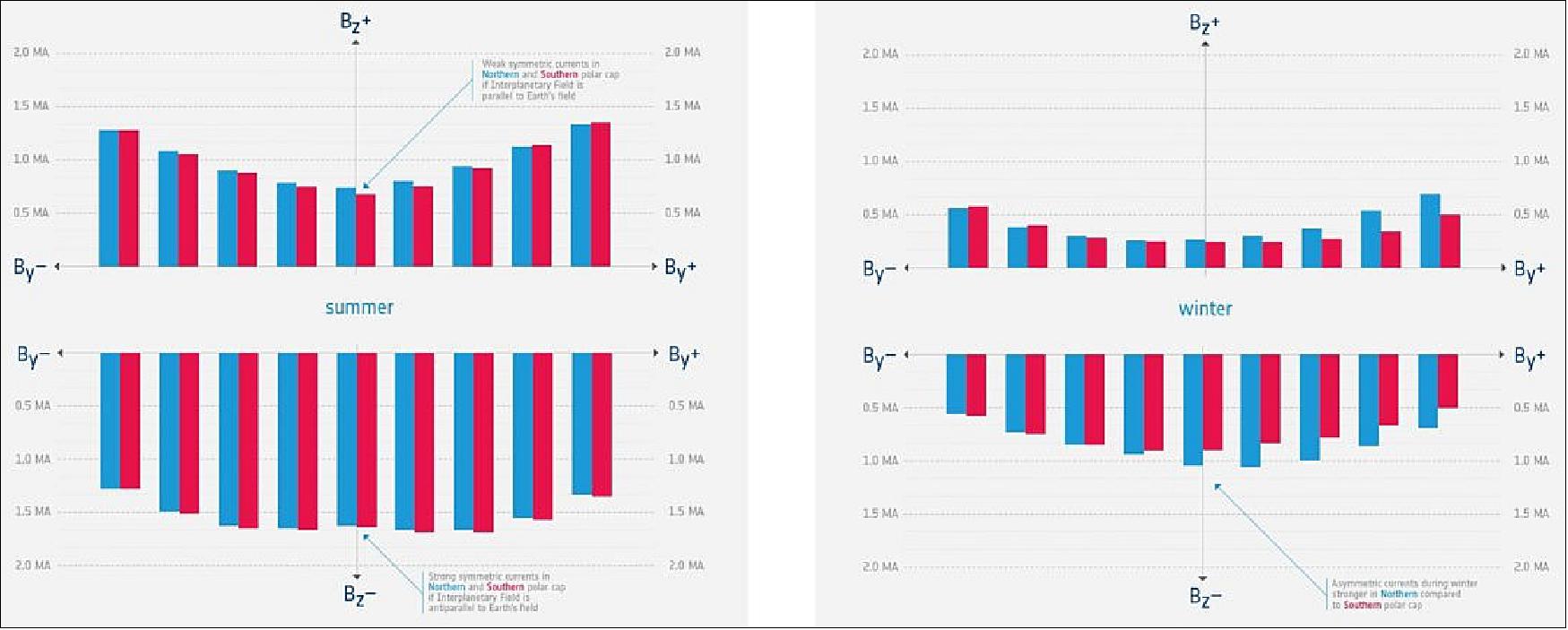

• January 12, 2021: Using information from ESA’s Swarm satellite constellation, scientists have made a discovery about how energy generated by electrically-charged particles in the solar wind flows into Earth’s atmosphere – surprisingly, more of it heads towards the magnetic north pole than towards the magnetic south pole. 68)

- The Sun bathes our planet with the light and heat to sustain life, but it also bombards us with dangerous charged particles in the solar wind. These charged particles have the potential to damage communication networks, navigation systems such as GPS and satellites. Severe solar storms can even cause power outages, such as the major blackout that Quebec in Canada suffered in 1989.

- Our magnetic field largely shields us from this onslaught.

- Generated mainly by an ocean of superheated, swirling liquid iron that makes up the outer core around 3000 km beneath our feet, Earth’s magnetic field is like a huge bubble protecting us from cosmic radiation and the charged particles carried by powerful winds that escape the Sun’s gravitational pull and sweep across the Solar System.

- Like a bar magnet, Earth’s magnetic field at the surface is defined by the north and south poles that align loosely with the axis of rotation.

- The aurorae offer visual displays of the consequences of charged particles from the Sun interacting with Earth’s magnetic field.

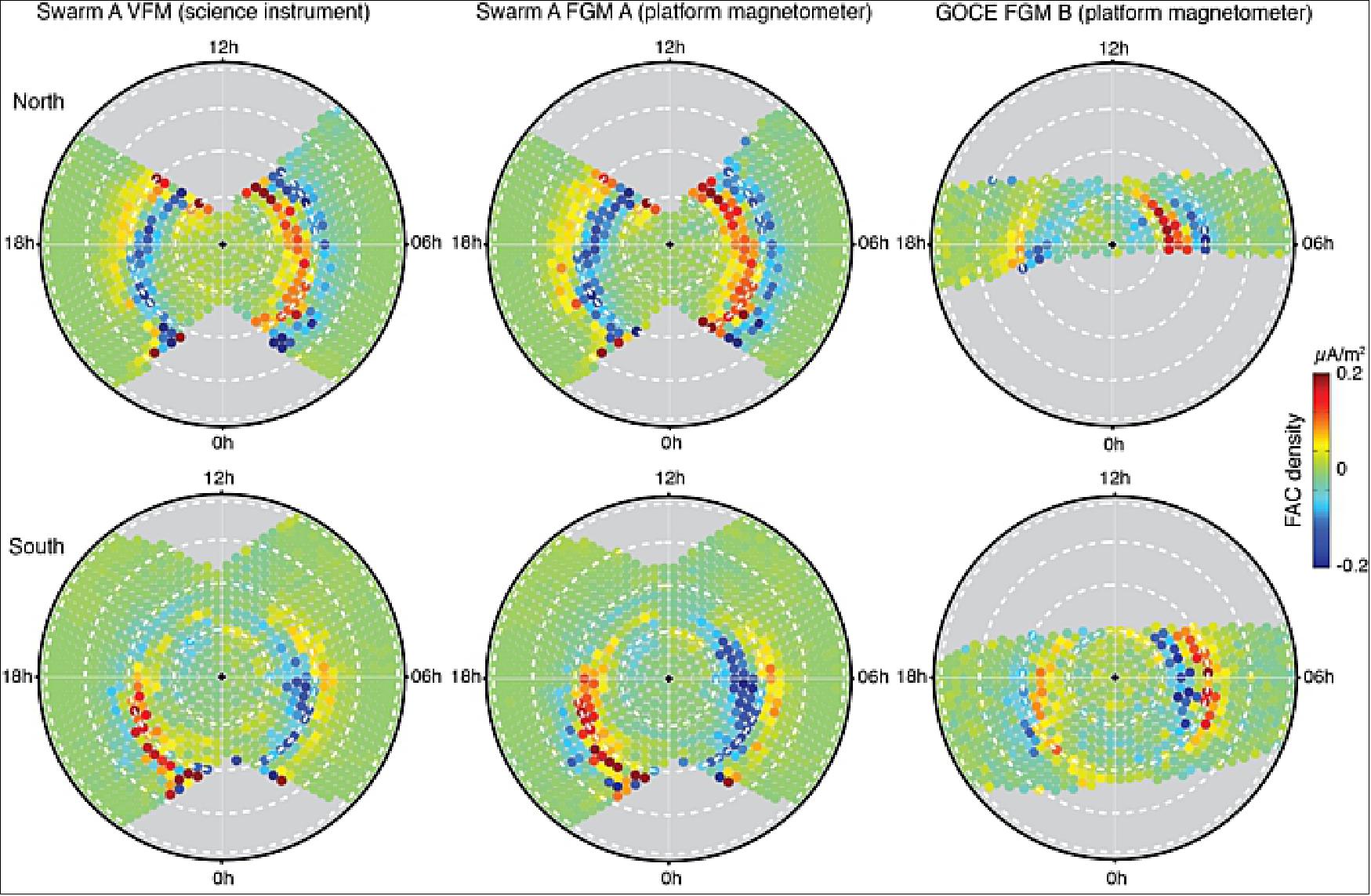

- Until now, it was assumed the same amount of electromagnetic energy would reach both hemispheres. However, a paper, published in Nature Communications, describes how research led by scientists from the University of Alberta in Canada used data from ESA’s Swarm mission to discover, unexpectedly, that the electromagnetic energy transported by space weather clearly prefers the north. 69)

- These new findings suggest that in addition to shielding Earth from incoming solar radiation, the magnetic field also actively controls how the energy is distributed and channelled into the upper atmosphere.

- The paper’s lead author, Ivan Pakhotin who is carrying out this research as part of ESA’s Living Planet Fellowship, explains, “Because the south magnetic pole is further away from Earth’s spin axis than the north magnetic pole, an asymmetry is imposed on how much energy makes its way down towards Earth in the north and south. There seems to be a differential reflection of electromagnetic plasma waves, known as Alfven waves.

- “We are not yet sure what the effects of this asymmetry might be, but it could also indicate a possible asymmetry in space weather and perhaps also between the Aurora Australis in the south and the Aurora Borealis in the north. Our findings also suggest that the dynamics of upper-atmospheric chemistry may vary between the hemispheres, especially during times of strong geomagnetic activity.”

- Ian Mann from the University of Alberta said, “The Sun’s activity, such as mass coronal ejections, can have potentially serious consequences for our modern way of living. Therefore, studying the underlying physics of space weather and the complexities of our magnetic field is very important to building up early warning systems and designing electrical grids better able to withstand the disturbances the Sun throws at us.

- “We are fortunate that we have ESA’s three Swarm satellites in orbit, delivering key information that is not only vital for our scientific research, but can also lead to some very practical solutions for our daily lives.”

- In orbit since 2013, the three identical Swarm satellites have not only returned information about how our magnetic field protects us from the dangerous particles in solar wind, but about how the field is generated, how it varies and how the position of magnetic north is changing.

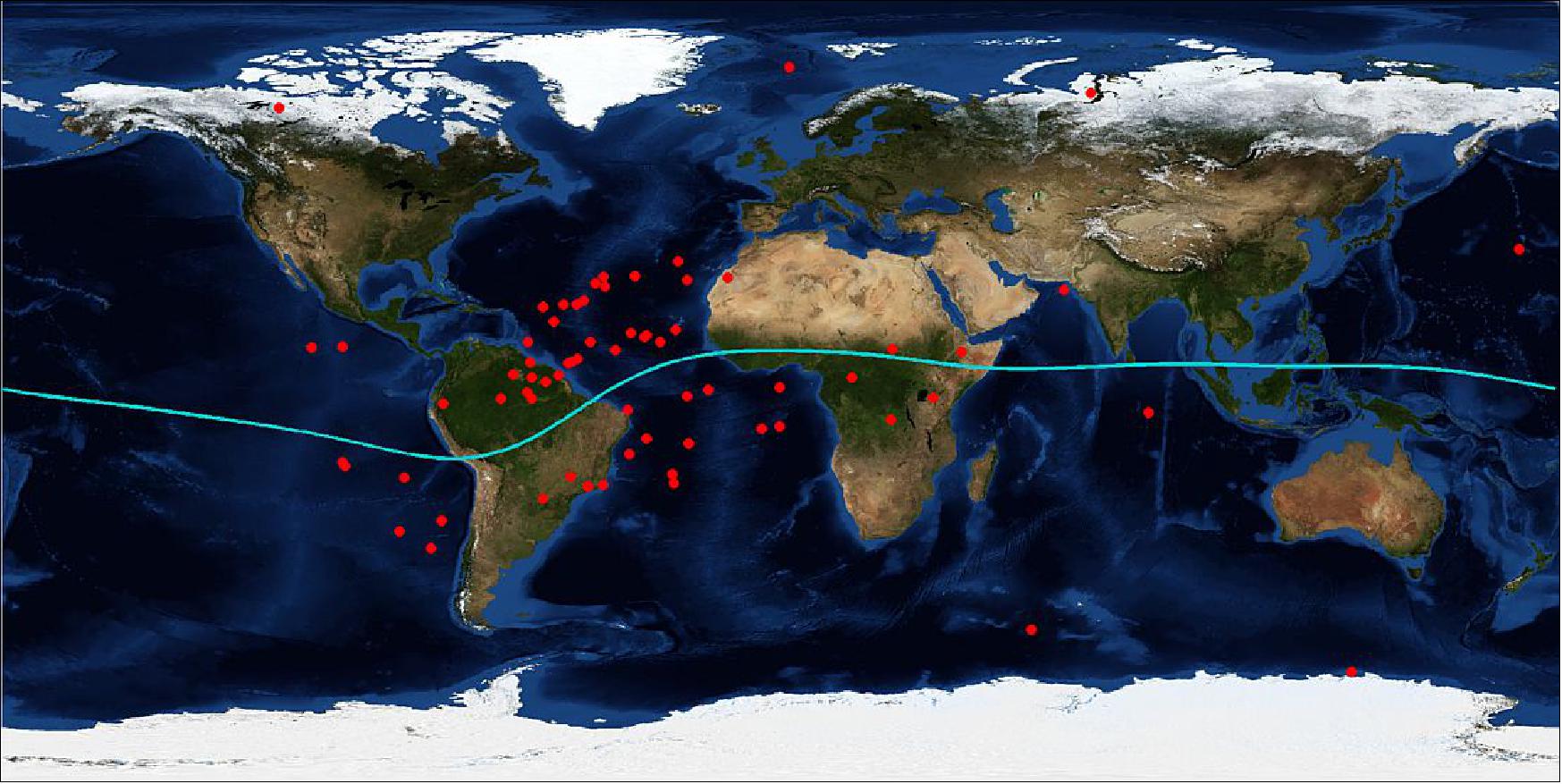

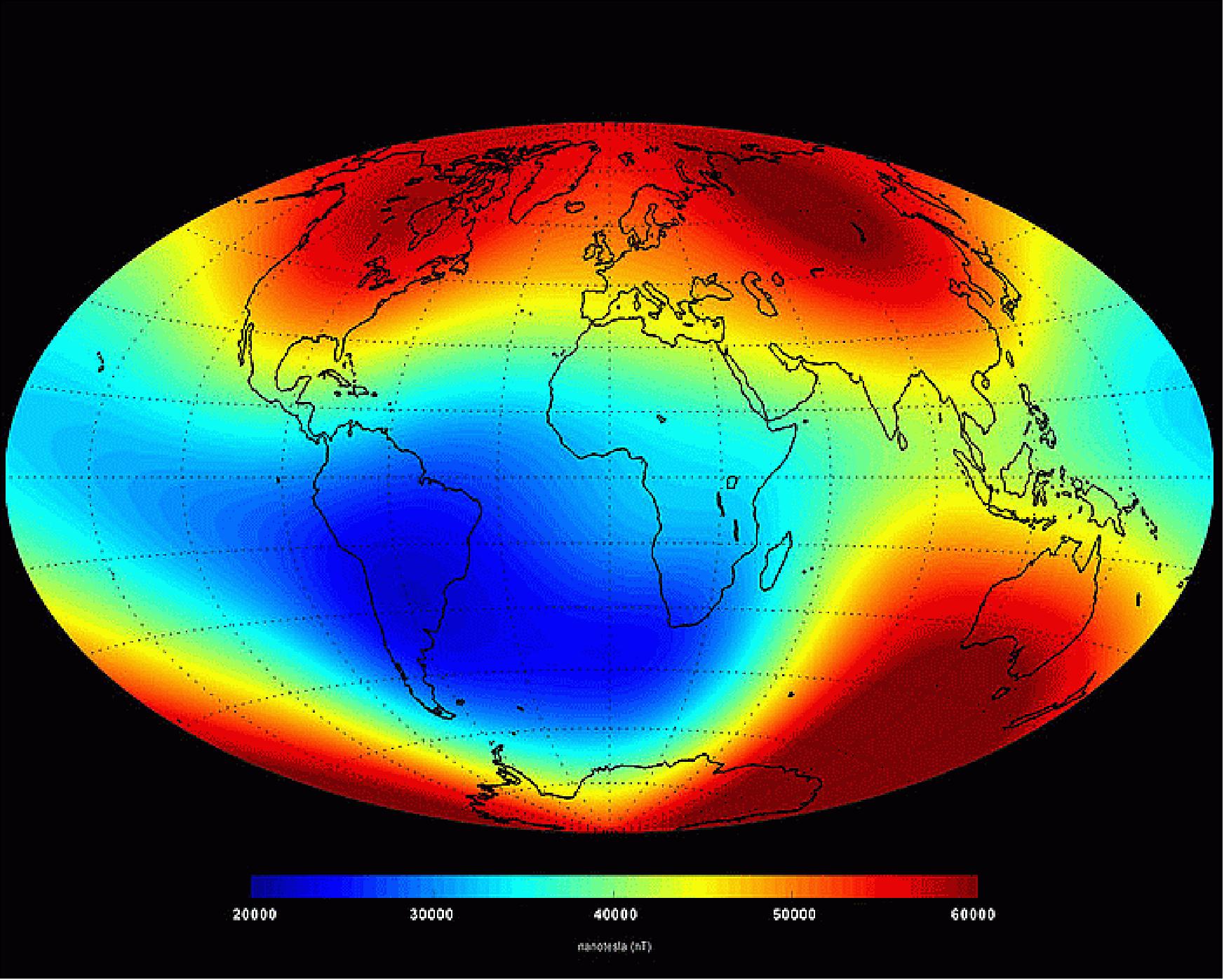

• August 17, 2020: A small but evolving dent in Earth’s magnetic field can cause big headaches for satellites. -Earth’s magnetic field acts like a protective shield around the planet, repelling and trapping charged particles from the Sun. But over South America and the southern Atlantic Ocean, an unusually weak spot in the field – called the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA) – allows these particles to dip closer to the surface than normal. Particle radiation in this region can knock out onboard computers and interfere with the data collection of satellites that pass through it – a key reason why NASA scientists want to track and study the anomaly. 70)

- The South Atlantic Anomaly is also of interest to NASA’s Earth scientists who monitor the changes in magnetic field strength there, both for how such changes affect Earth's atmosphere and as an indicator of what's happening to Earth's magnetic fields, deep inside the globe.

- Currently, the SAA creates no visible impacts on daily life on the surface. However, recent observations and forecasts show that the region is expanding westward and continuing to weaken in intensity. It is also splitting – recent data shows the anomaly’s valley, or region of minimum field strength, has split into two lobes, creating additional challenges for satellite missions.

- A host of NASA scientists in geomagnetic, geophysics, and heliophysics research groups observe and model the SAA, to monitor and predict future changes – and help prepare for future challenges to satellites and humans in space.

It’s what’s inside that counts

- The South Atlantic Anomaly arises from two features of Earth’s core: The tilt of its magnetic axis, and the flow of molten metals within its outer core.

- Earth is a bit like a bar magnet, with north and south poles that represent opposing magnetic polarities and invisible magnetic field lines encircling the planet between them. But unlike a bar magnet, the core magnetic field is not perfectly aligned through the globe, nor is it perfectly stable. That’s because the field originates from Earth’s outer core: molten, iron-rich and in vigorous motion 1800 miles below the surface. These churning metals act like a massive generator, called the geodynamo, creating electric currents that produce the magnetic field.

- As the core motion changes over time, due to complex geodynamic conditions within the core and at the boundary with the solid mantle up above, the magnetic field fluctuates in space and time too. These dynamical processes in the core ripple outward to the magnetic field surrounding the planet, generating the SAA and other features in the near-Earth environment – including the tilt and drift of the magnetic poles, which are moving over time. These evolutions in the field, which happen on a similar time scale to the convection of metals in the outer core, provide scientists with new clues to help them unravel the core dynamics that drive the geodynamo.

- “The magnetic field is actually a superposition of fields from many current sources,” said Terry Sabaka, a geophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Regions outside of the solid Earth also contribute to the observed magnetic field. However, he said, the bulk of the field comes from the core.

- The forces in the core and the tilt of the magnetic axis together produce the anomaly, the area of weaker magnetism – allowing charged particles trapped in Earth’s magnetic field to dip closer to the surface.

- The Sun expels a constant outflow of particles and magnetic fields known as the solar wind and vast clouds of hot plasma and radiation called coronal mass ejections. When this solar material streams across space and strikes Earth’s magnetosphere, the space occupied by Earth’s magnetic field, it can become trapped and held in two donut-shaped belts around the planet called the Van Allen Belts. The belts restrain the particles to travel along Earth’s magnetic field lines, continually bouncing back and forth from pole to pole. The innermost belt begins about 400 miles from the surface of Earth, which keeps its particle radiation a healthy distance from Earth and its orbiting satellites.

- However, when a particularly strong storm of particles from the Sun reaches Earth, the Van Allen belts can become highly energized and the magnetic field can be deformed, allowing the charged particles to penetrate the atmosphere.

- “The observed SAA can be also interpreted as a consequence of weakening dominance of the dipole field in the region,” said Weijia Kuang, a geophysicist and mathematician in Goddard’s Geodesy and Geophysics Laboratory. “More specifically, a localized field with reversed polarity grows strongly in the SAA region, thus making the field intensity very weak, weaker than that of the surrounding regions.”

A pothole in space

- Although the South Atlantic Anomaly arises from processes inside Earth, it has effects that reach far beyond Earth’s surface. The region can be hazardous for low-Earth orbit satellites that travel through it. If a satellite is hit by a high-energy proton, it can short-circuit and cause an event called SEU (Single Event Upset). This can cause the satellite’s function to glitch temporarily or can cause permanent damage if a key component is hit. In order to avoid losing instruments or an entire satellite, operators commonly shut down non-essential components as they pass through the SAA. Indeed, NASA's ICON (Ionospheric Connection Explorer) regularly travels through the region and so the mission keeps constant tabs on the SAA's position.

- The International Space Station, which is in low-Earth orbit, also passes through the SAA. It is well protected, and astronauts are safe from harm while inside. However, the ISS has other passengers affected by the higher radiation levels: Instruments like the GEDI (Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation) mission, collect data from various positions on the outside of the ISS. The SAA causes “blips” on GEDI’s detectors and resets the instrument’s power boards about once a month, said Bryan Blair, the mission’s deputy principal investigator and instrument scientist, and a lidar instrument scientist at Goddard.

- “These events cause no harm to GEDI,” Blair said. “The detector blips are rare compared to the number of laser shots – about one blip in a million shots – and the reset line event causes a couple of hours of lost data, but it only happens every month or so.”

- In addition to measuring the SAA’s magnetic field strength, NASA scientists have also studied the particle radiation in the region with the SAMPEX (Solar, Anomalous, and Magnetospheric Particle Explorer) – the first of NASA’s Small Explorer missions, launched in 1992 and providing observations until 2012. One study, led by NASA heliophysicist Ashley Greeley as part of her doctoral thesis, used two decades of data from SAMPEX to show that the SAA is slowly but steadily drifting in a northwesterly direction. The results helped confirm models created from geomagnetic measurements and showed how the SAA’s location changes as the geomagnetic field evolves.

- “These particles are intimately associated with the magnetic field, which guides their motions,” said Shri Kanekal, a researcher in the Heliospheric Physics Laboratory at NASA Goddard. “Therefore, any knowledge of particles gives you information on the geomagnetic field as well.”

- Greeley’s results, published in the journal Space Weather, were also able to provide a clear picture of the type and amount of particle radiation satellites receive when passing through the SAA, which emphasized the need for continuing monitoring in the region.

- The information Greeley and her collaborators garnered from SAMPEX’s in-situ measurements has also been useful for satellite design. Engineers for the Low-Earth Orbit, or LEO, satellite used the results to design systems that would prevent a latch-up event from causing failure or loss of the spacecraft.

Modelling a safer future for satellites

- In order to understand how the SAA is changing and to prepare for future threats to satellites and instruments, Sabaka, Kuang and their colleagues use observations and physics to contribute to global models of Earth’s magnetic field.

- The team assesses the current state of the magnetic field using data from the European Space Agency’s Swarm constellation, previous missions from agencies around the world, and ground measurements. Sabaka’s team teases apart the observational data to separate out its source before passing it on to Kuang’s team. They combine the sorted data from Sabaka’s team with their core dynamics model to forecast geomagnetic secular variation (rapid changes in the magnetic field) into the future.

- The geodynamo models are unique in their ability to use core physics to create near-future forecasts, said Andrew Tangborn, a mathematician in Goddard’s Planetary Geodynamics Laboratory.

- “This is similar to how weather forecasts are produced, but we are working with much longer time scales,” he said. “This is the fundamental difference between what we do at Goddard and most other research groups modeling changes in Earth’s magnetic field.”

- One such application that Sabaka and Kuang have contributed to is the IGRF (International Geomagnetic Reference Field). Used for a variety of research from the core to the boundaries of the atmosphere, the IGRF is a collection of candidate models made by worldwide research teams that describe Earth’s magnetic field and track how it changes in time.

- “Even though the SAA is slow-moving, it is going through some change in morphology, so it’s also important that we keep observing it by having continued missions,” Sabaka said. “Because that’s what helps us make models and predictions.”

- The changing SAA provides researchers new opportunities to understand Earth’s core, and how its dynamics influence other aspects of the Earth system, said Kuang. By tracking this slowly evolving “dent” in the magnetic field, researchers can better understand the way our planet is changing and help prepare for a safer future for satellites.

• May 20, 2020: In an area stretching from Africa to South America, Earth’s magnetic field is gradually weakening. This strange behavior has geophysicists puzzled and is causing technical disturbances in satellites orbiting Earth. Scientists are using data from ESA’s Swarm constellation to improve our understanding of this area known as the ‘South Atlantic Anomaly.’ 71)

- Earth’s magnetic field is vital to life on our planet. It is a complex and dynamic force that protects us from cosmic radiation and charged particles from the Sun. The magnetic field is largely generated by an ocean of superheated, swirling liquid iron that makes up the outer core around 3000 km beneath our feet. Acting as a spinning conductor in a bicycle dynamo, it creates electrical currents, which in turn, generate our continuously changing electromagnetic field.

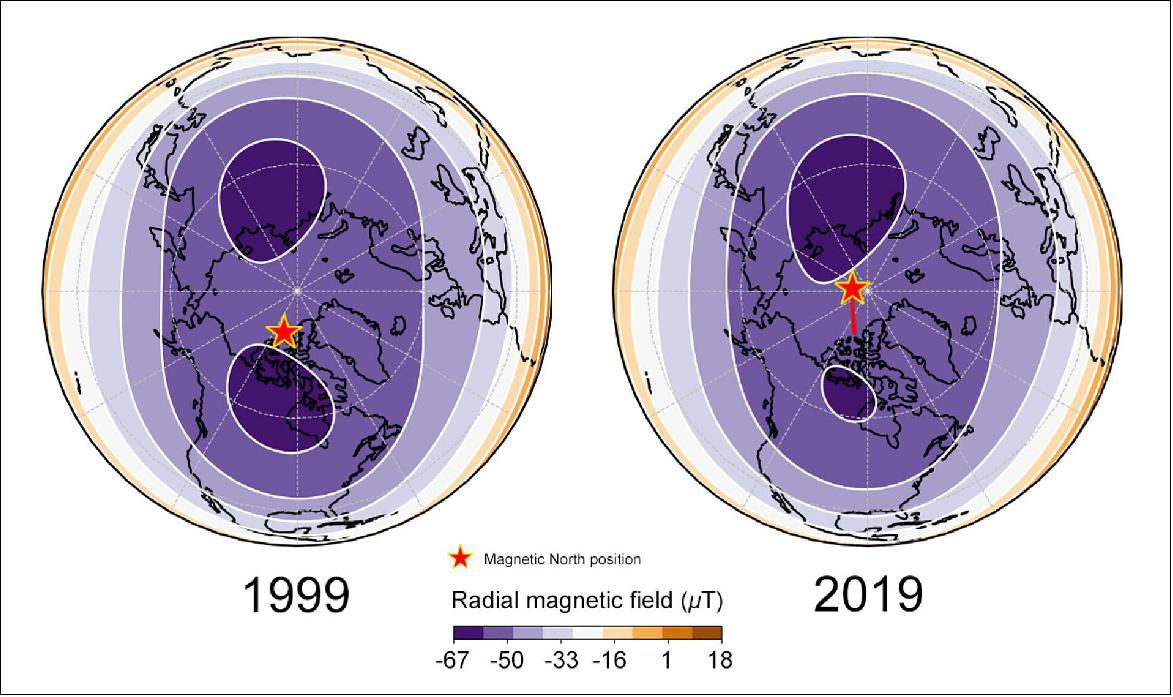

- This field is far from static and varies both in strength and direction. For example, recent studies have shown that the position of the north magnetic pole is changing rapidly.

- Over the last 200 years, the magnetic field has lost around 9% of its strength on a global average. A large region of reduced magnetic intensity has developed between Africa and South America and is known as the South Atlantic Anomaly.

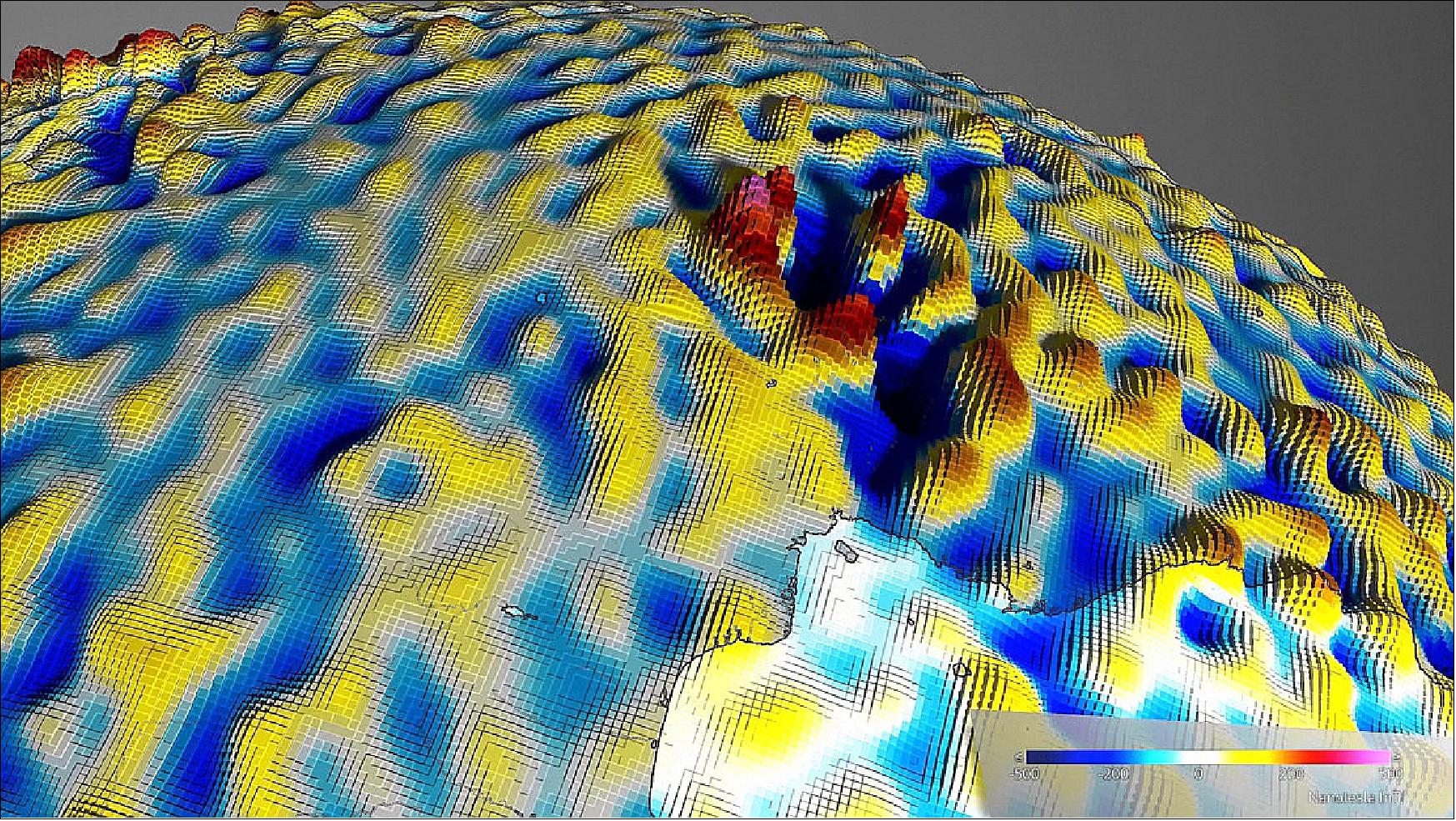

- From 1970 to 2020, the minimum field strength in this area has dropped from around 24,000 nanoteslas (nT) to 22,000, while at the same time the area of the anomaly has grown and moved westward at a pace of around 20 km per year. Over the past five years, a second center of minimum intensity has emerged southwest of Africa – indicating that the South Atlantic Anomaly could split up into two separate cells.

- Earth’s magnetic field is often visualized as a powerful dipolar bar magnet at the center of the planet, tilted at around 11° to the axis of rotation. However, the growth of the South Atlantic Anomaly indicates that the processes involved in generating the field are far more complex. Simple dipolar models are unable to account for the recent development of the second minimum.

- Scientists from the Swarm Data, Innovation and Science Cluster (DISC) are using data from ESA’s Swarm satellite constellation to better understand this anomaly. Swarm satellites are designed to identify and precisely measure the different magnetic signals that make up Earth’s magnetic field.

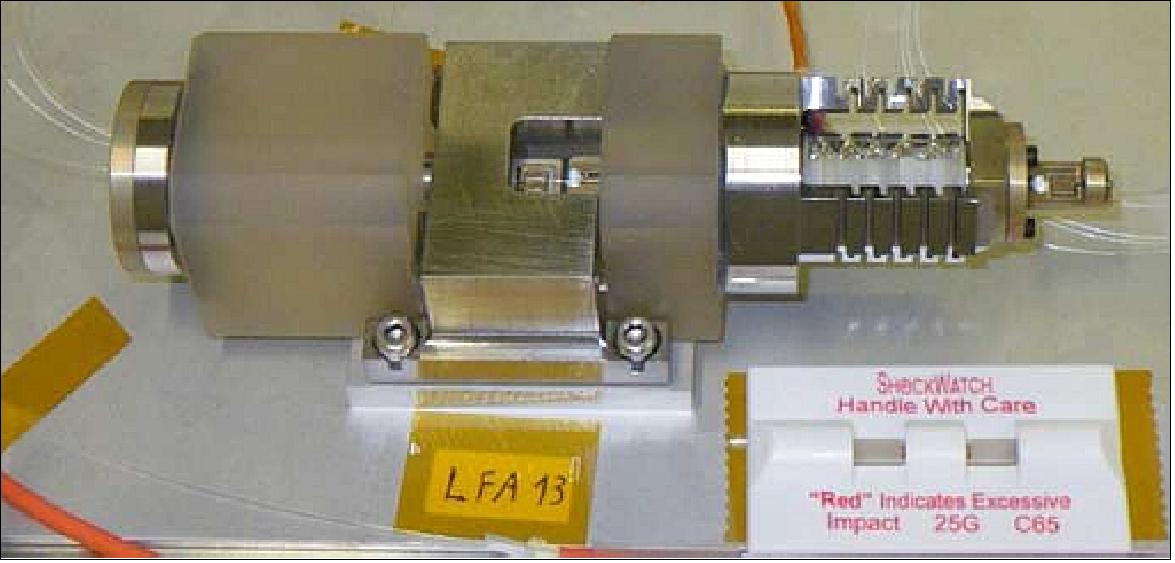

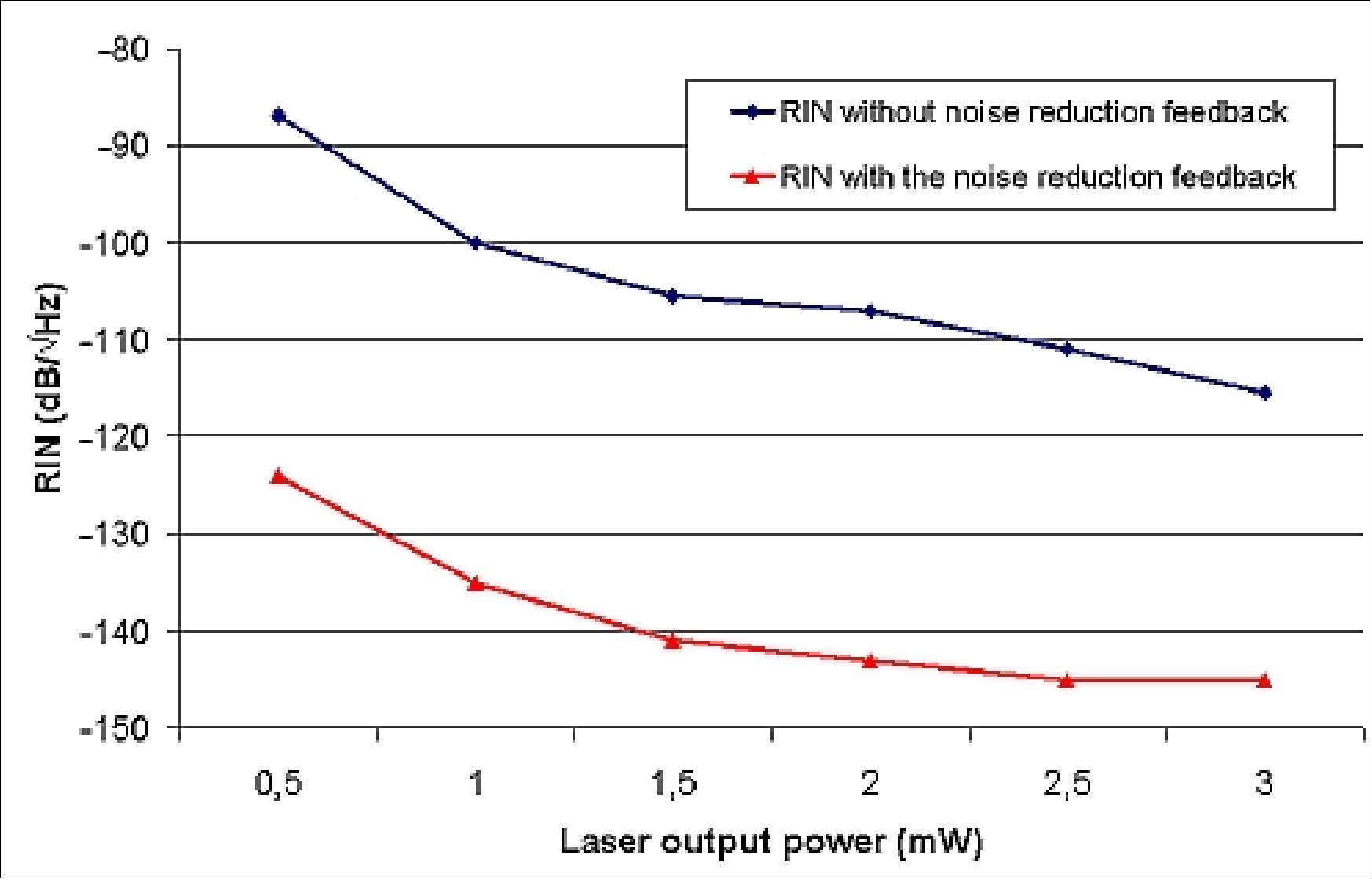

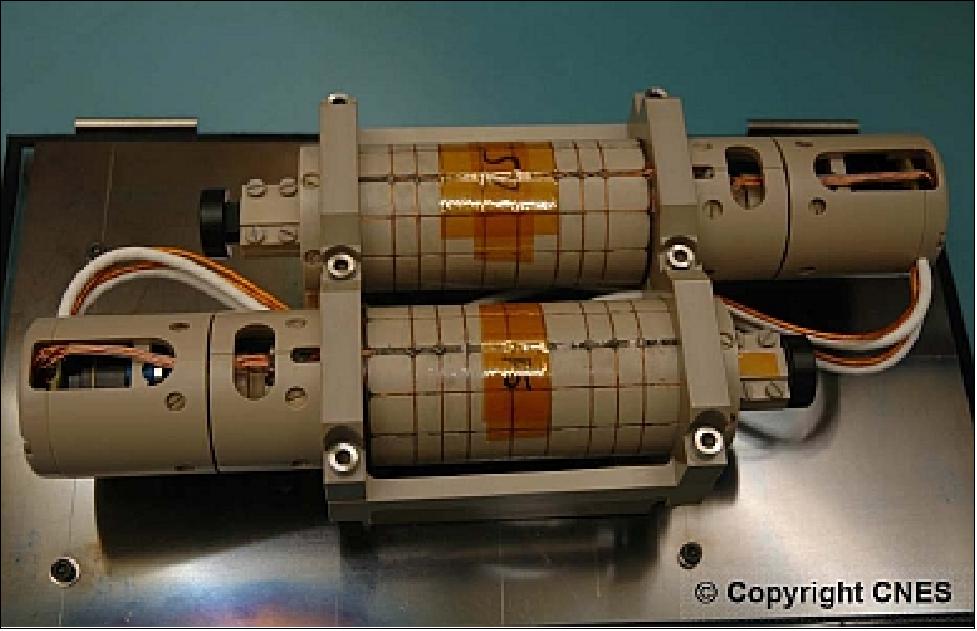

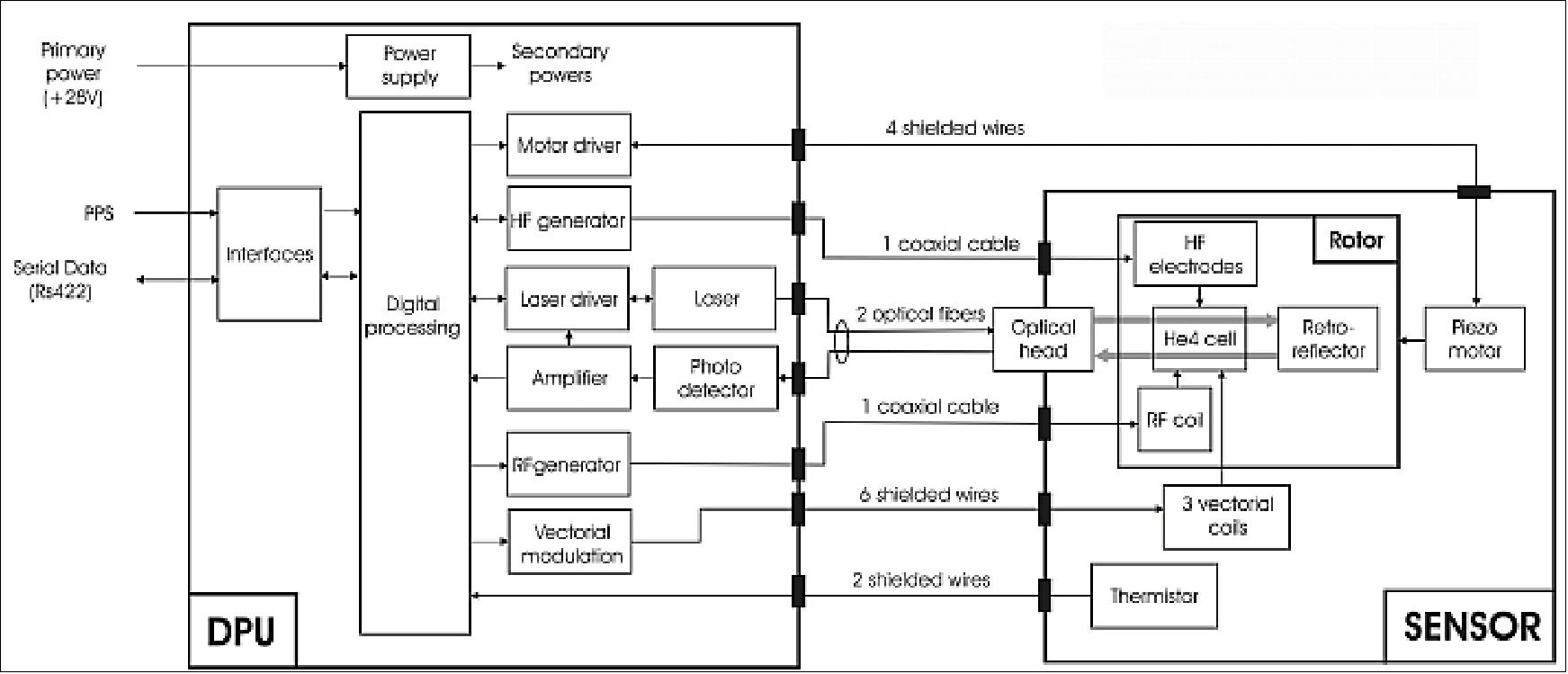

- Jürgen Matzka, from the German Research Center for Geosciences, says, “The new, eastern minimum of the South Atlantic Anomaly has appeared over the last decade and in recent years is developing vigorously. We are very lucky to have the Swarm satellites in orbit to investigate the development of the South Atlantic Anomaly. The challenge now is to understand the processes in Earth’s core driving these changes.”