ISS: Columbus Module

EO

ESA

Operational (extended)

Quick facts

Overview

| Mission type | EO |

| Agency | ESA |

| Mission status | Operational (extended) |

| Launch date | 07 Feb 2008 |

ISS Utilization: Columbus Module of ESA

Launch Experiments Payloads Module Status References

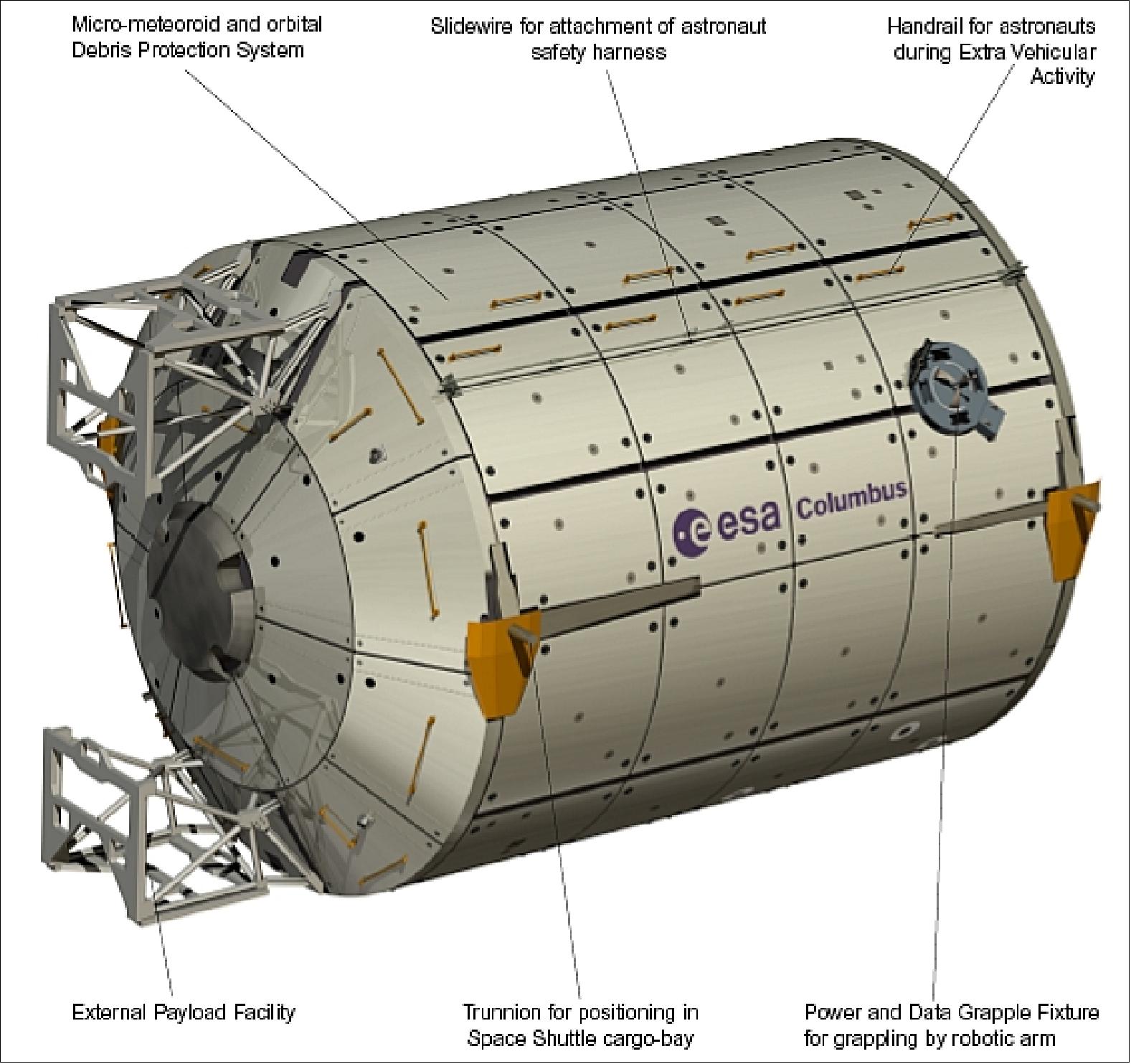

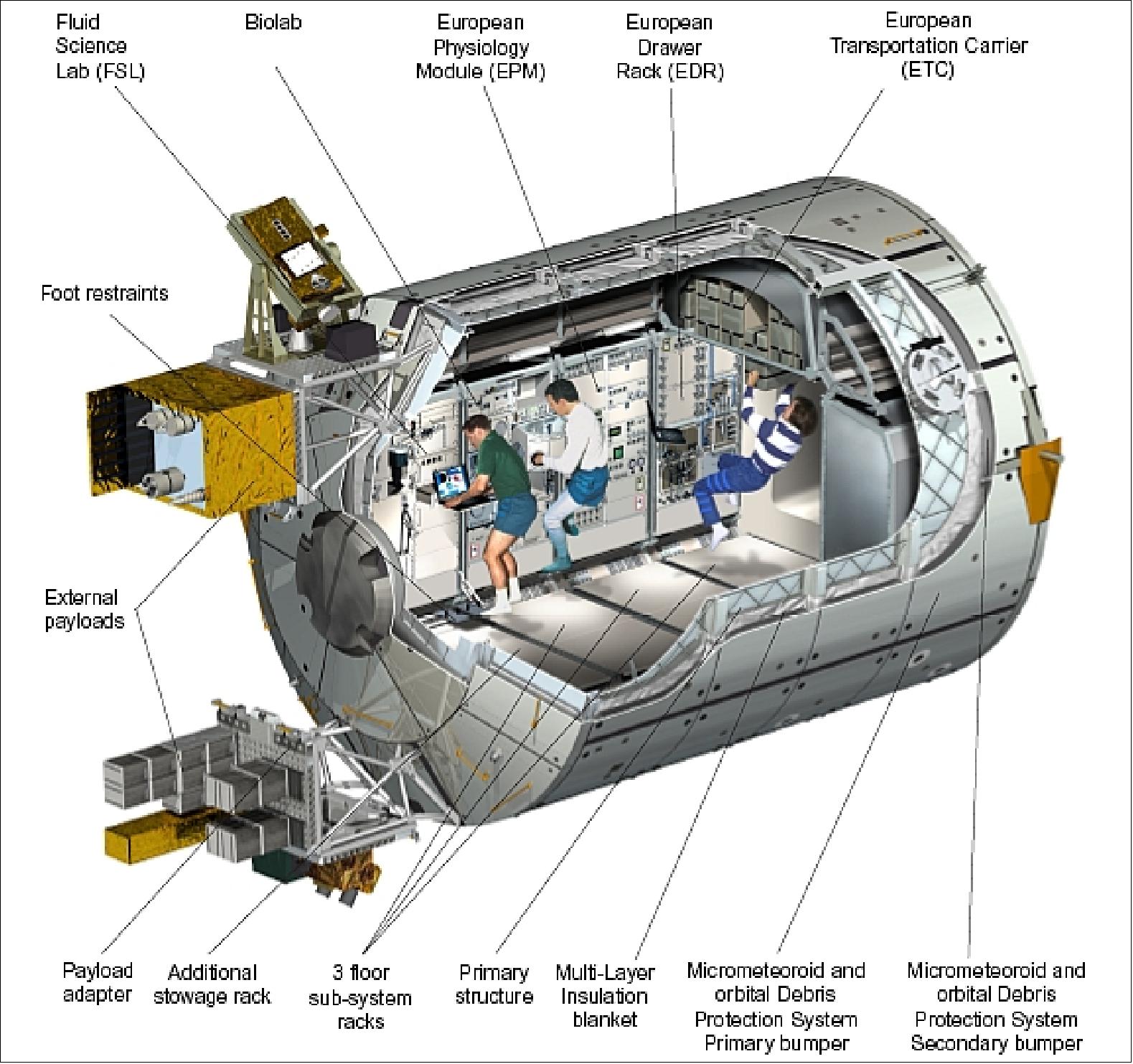

The Columbus laboratory is ESA's biggest single contribution to the International Space Station. The 4.5 m diameter cylindrical module of 6.9 m in length is equipped with flexible research facilities that offer extensive science capabilities. The Columbus module provides internal accommodation for experiments in the field of multidisciplinary research into material science, fluid physics and life science. In addition, an external payload facility hosts experiments and applications in the field of space science, Earth observation and technology demonstrations. 1) 2) 3) 4)

Role | Pressurized science laboratory with 10 internal ISPR (International Standard Payload Rack) spaces |

Launch date | Feb. 7, 2008 on Shuttle flight STS-122 |

Launch mass of module | 10,275 kg (empty), 12,775 kg (mass at launch containing 2500 kg of payload mass) |

Columbus size | Module length = 6.9 m, outside diameter = 4.5 m |

Columbus internal volume | 75 m3 (total), a volume of 25 m3 is being used for the 10 payload racks |

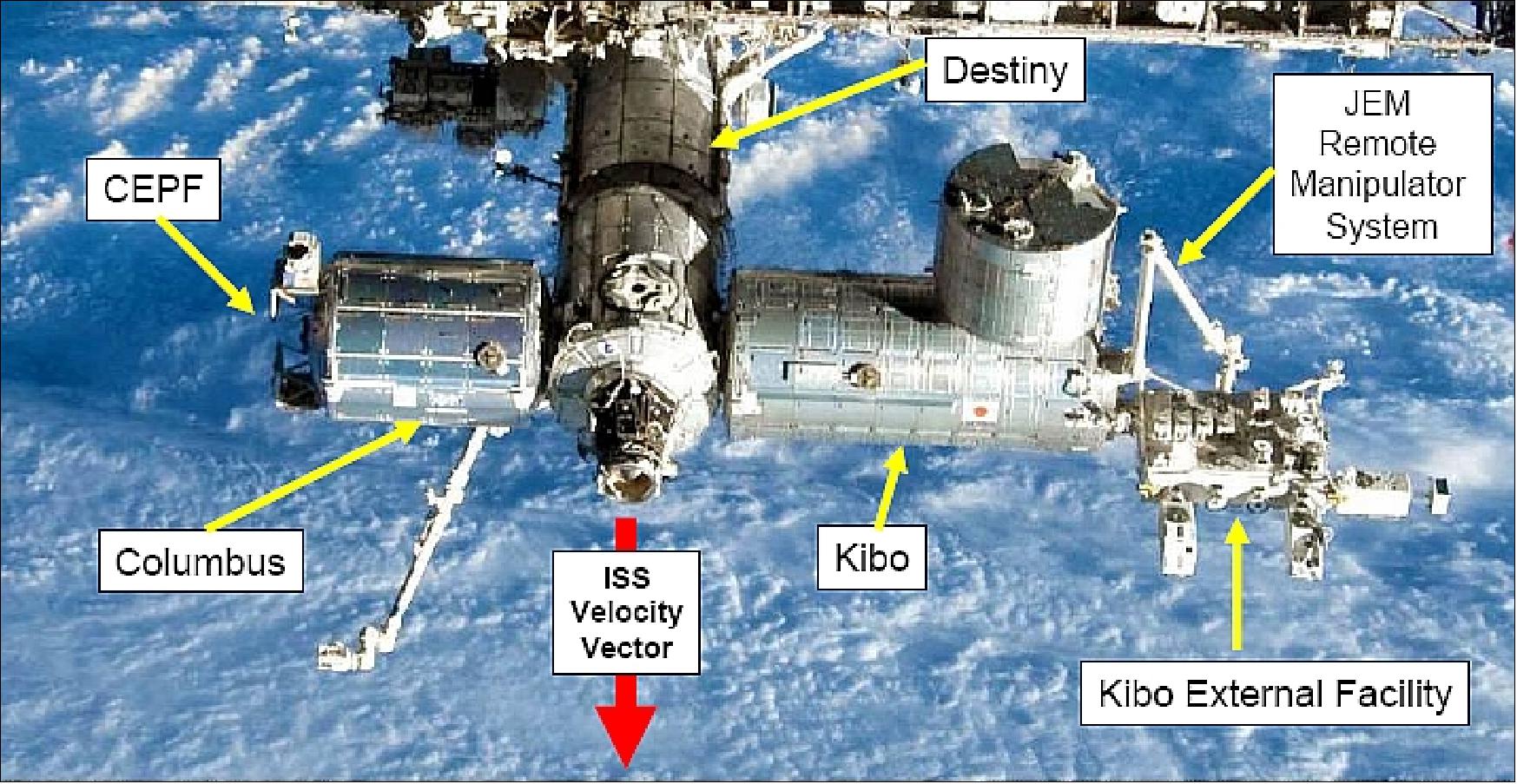

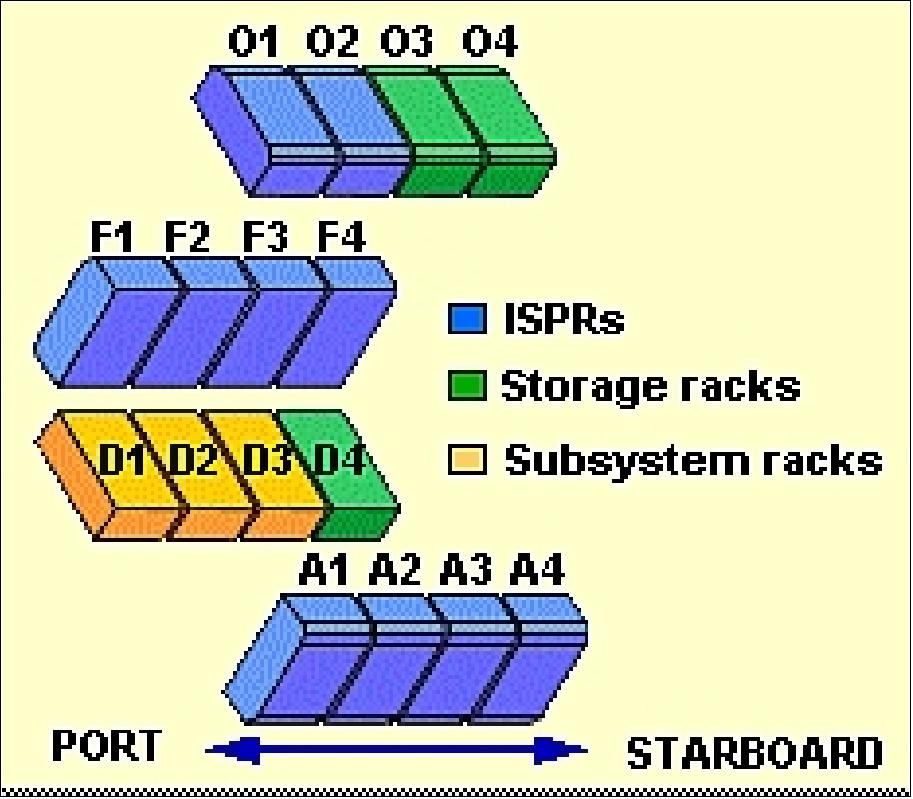

On-orbit configuration | - Columbus module is attached to the Node 2 starboard docking port - 10 ISPR racks (mass of 998 kg each) |

Environmental control | - Supported crew of 3 |

Launch

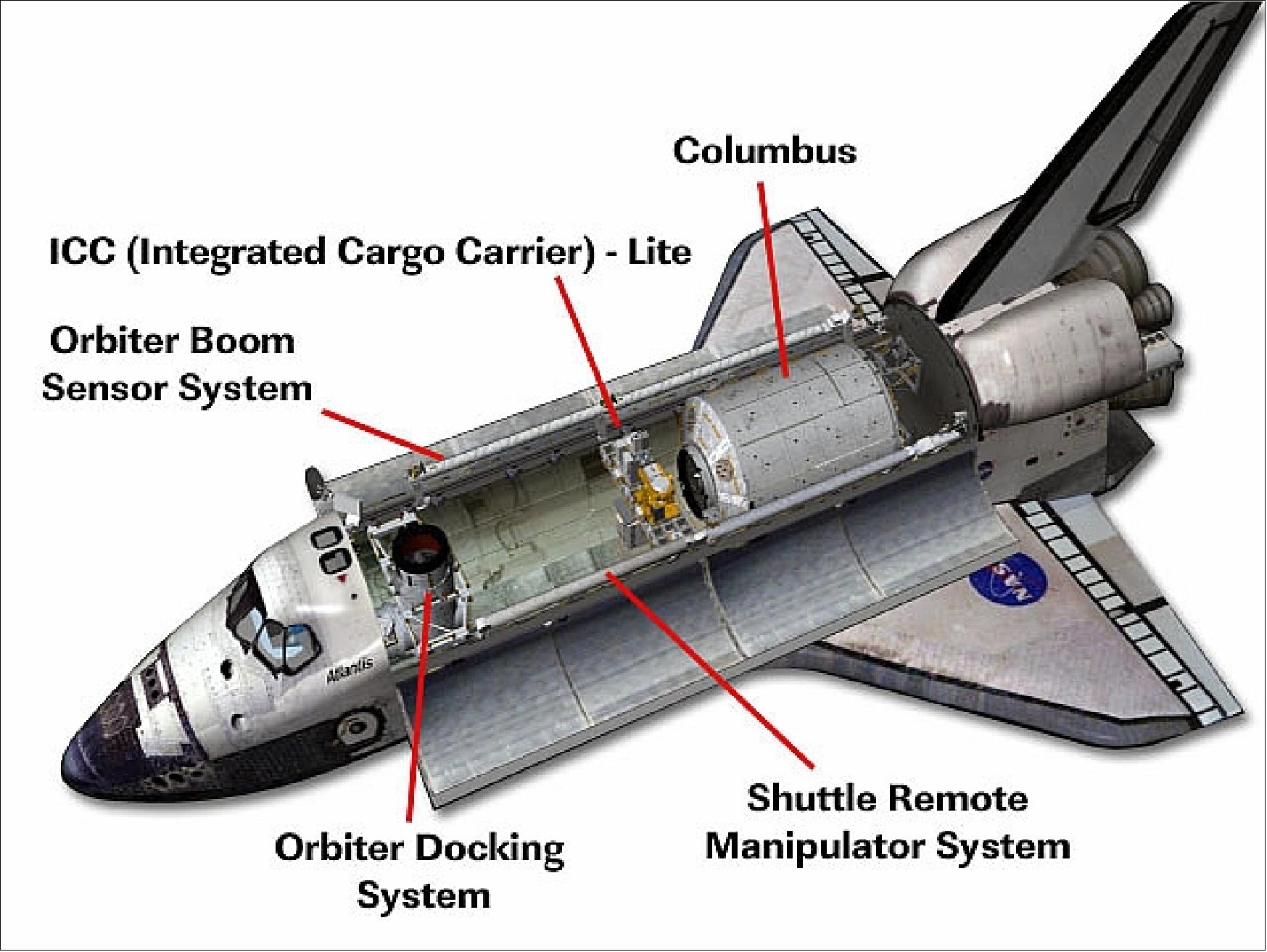

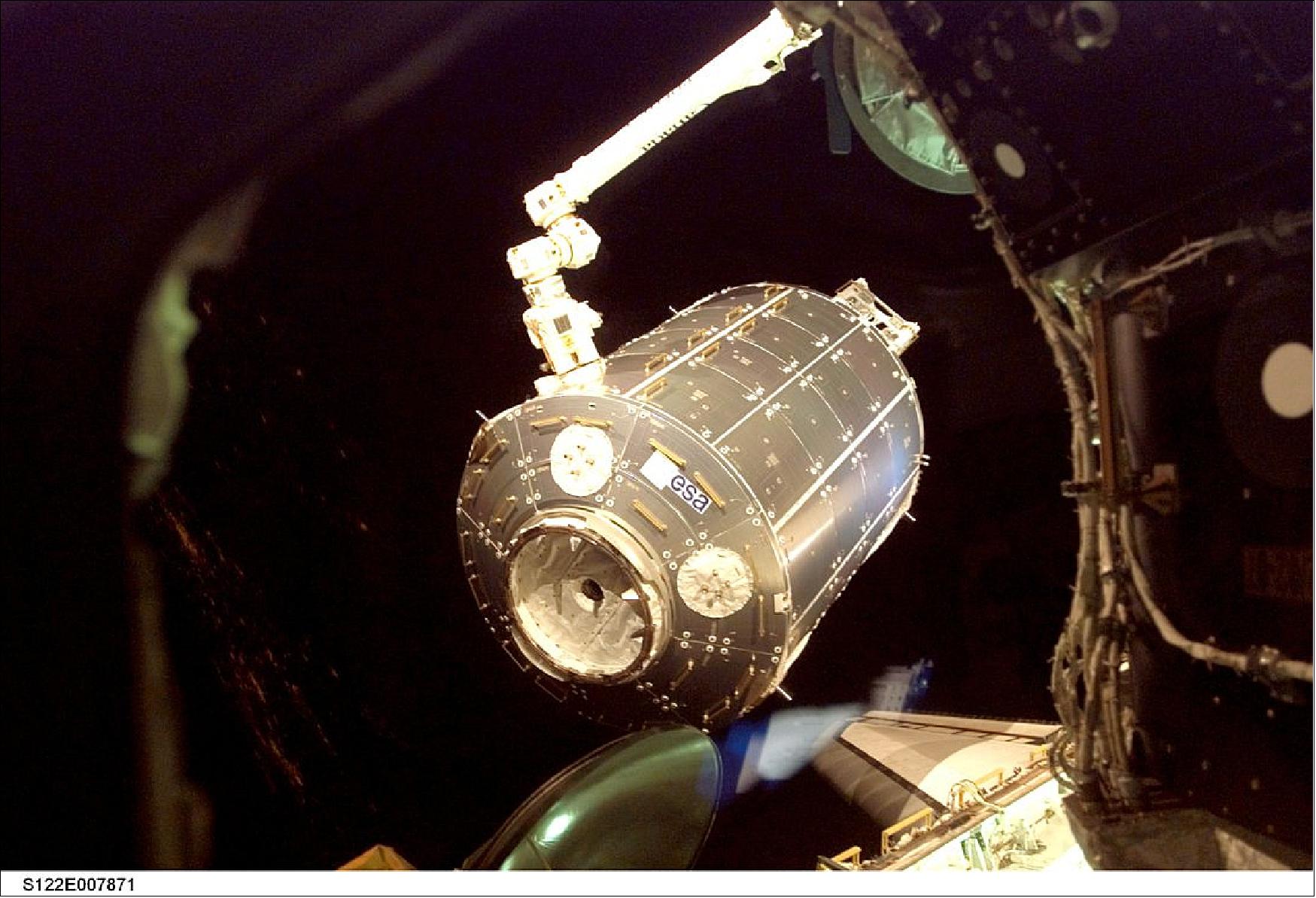

The Columbus module was launched on Shuttle flight STS-122 (assembly flight 1E of Atlantis) of NASA on February 7, 2008 (13 day mission). 6)

On February 11, 2008 (four days after launch), the Columbus module was attached to the starboard side of the Node 2 module of ISS. The Columbus module is permanently docked to the ISS with an expected life of 10 years.

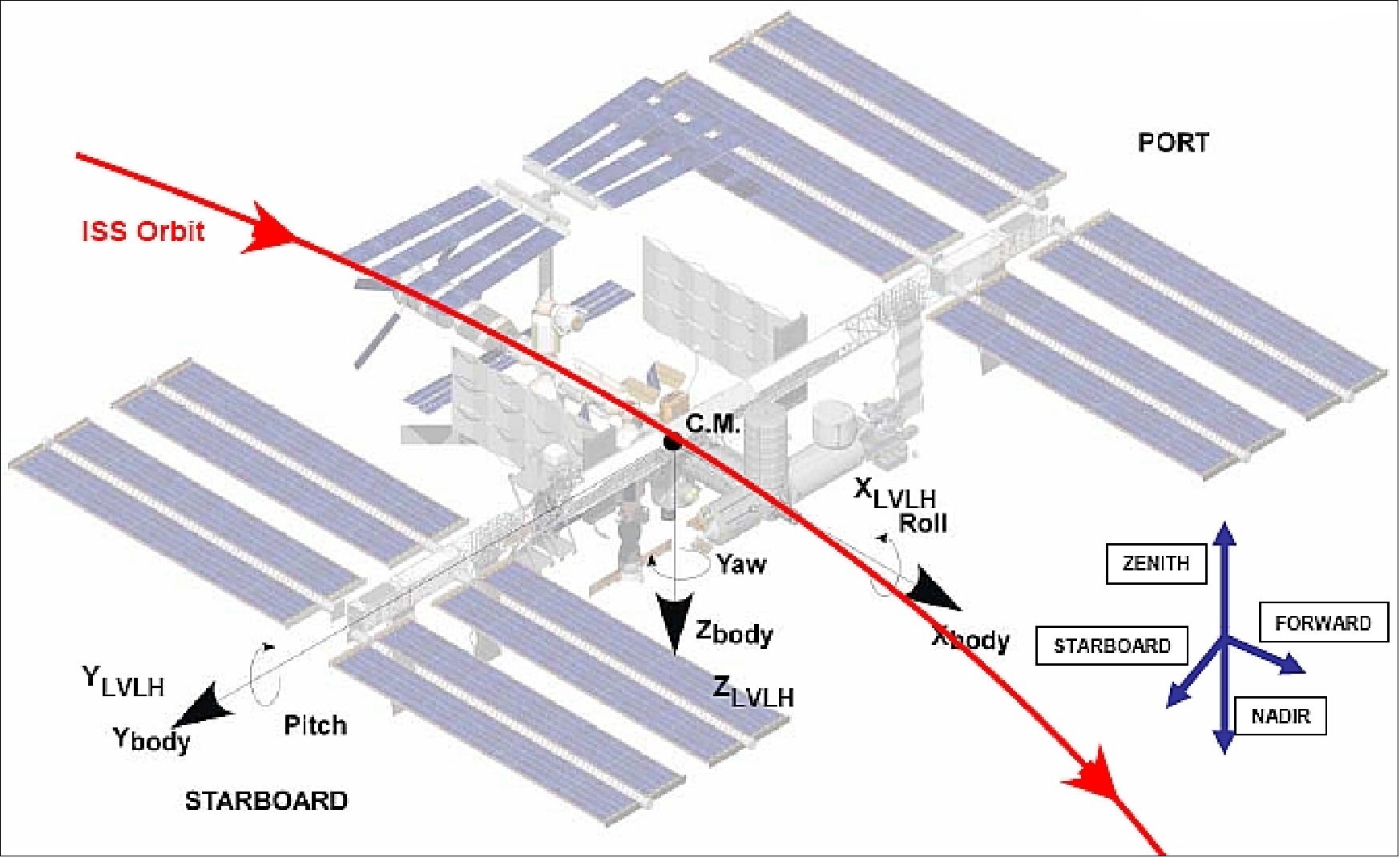

Orbit of ISS: Near-circular LEO (Low Earth Orbit), nominal altitude range of 340-460 km, inclination = 51.6º, ~16 orbits/day. Each successive orbit crosses the equator 22.5º to the west of the preceding orbit. The nodal regression is ~5º west/day, and the solar β angle is between 0º and ±75º. As an observation platform, ISS covers ~85% of Earth's surface and ~95% of the population.

ISS attitude characteristics for Earth observation:

• Torque equilibrium attitude during normal operations (~ 10º nose down and a few degrees nose left, no role with respect to LVLH (Local Vertical / Local Horizontal)

• LVLH during docking operations and maneuvers.

The ISS attitude is measured with star trackers and rate gyros:

• During nominal operations:

- The attitude is measured with a periodicity of ~±0.5º in each axis over one orbit (smooth sinusoidal variation)

- The attitude can be predicted up with accuracy of approx 0.2º for up to 4 days.

• During docking and/or maneuver periods:

- Attitude variations of several degrees possible during docking operations

- Maneuvers (reboots): ~2-3º variation during a short period (1-2 orbits).

Background

In the early 1980s, NASA started to persue the objective of developing a continuously manned station in low Earth orbit. Actually, the idea had been around for many years and had long been a part of NASA's plans. Obviously, such a large program was only realizable on the basis of an international partnership. This was still the era of the Cold War.

The Columbus history began in Rome, Italy in January 1985, when ESA approved the eponymous Columbus program. The plan then was to build three modules: an Attached Pressurized Module (APM) to dock with the space station, a Man-Tended Free-Flyer (MTFF) to float freely in space and conduct microgravity experiments away from the mass of the space station, and an autonomous platform in polar orbit for Earth observation. In the end, only the APM module, now called Columbus, has been realized. 7)

The following agreements represent important steps in the Columbus (and ISS) development program:

- On September 29, 1988, a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on cooperation in the design and development of the Space Station Freedom was signed by NASA and ESA in Washington D. C. 8)

- In the early 1990s, the United States, Russia, Japan, Canada and the member states of ESA (European Space Agency) started negotiations for the construction of a space station, this time an international one, initially called Alpha, but later renamed to International Space Station (ISS).

- The approval of Europe's participation in the ISS program which included Columbus, came in October 1995 at the ESA Ministerial Council in Toulouse, France. This approval lead to the signing of the contract to develop Columbus with the prime contractor EADS-Astrium in March 1996 (formerly Daimler Benz Aerospace, and the former MBB-ERNO, Bremen, Germany). 9) 10)

- In March 1997, ESA and NASA signed a MOU enabling "early utilization opportunities" of the International Space Station. The agreement formalized exchanges of goods and/or services between the participating parties without a corresponding financial transaction, i.e. without an exchange of funds. 11) 12)

The launch of Columbus is also covered by the same barter agreement with NASA signed on 5 March 1997. Originally, Columbus would have been launched on an Ariane 5 vehicle, though downscaling of the laboratory and the cost saving influence of using the MPLM (Multi-Purpose Logistics Module) principle structure for Columbus lead to the switch to a Shuttle launch. Under this agreement, in exchange for NASA launching Columbus and its initial payload aboard the Space Shuttle, ESA provides two of the Station's three Nodes (ISS connecting modules), spares and sustaining engineering for the Laboratory Support Equipment items provided by ESA to NASA under the Early Utilization Memorandum of Understanding, and hardware/support for software development and integration in the NASA ground software test and integration facilities for the ISS. ESA also placed responsibility for developing Nodes-2 and -3 with ASI (Italian Space Agency) in order to utilize the same structural concept as the MPLMs and Columbus.

- In 1997, ESA and ASI signed an agreement to cooperate on the development of manned space modules. Under this arrangement, ESA would provide the Columbus-derived ECLS (Environmental Control and Life Support) equipment for ASI's three MPLMs (Multi-Purpose Logistics Modules), which were developed for NASA by ASI to be used as pressurized cargo containers to travel in the Shuttle cargo bay. In exchange, ASI would provide the Columbus primary structure, derived from that of the MPLM.

- On January 29, 1998, a multilateral agreement was signed in Washington between the United States government and the governments of: Canada, Member States of ESA, Japan, and the Russian Federation - concerning cooperation on the civil International Space Station. The object of this Agreement was to establish a long-term international cooperative framework among the Partners, on the basis of genuine partnership, for the detailed design, development, operation, and utilization of a permanently inhabited civil international Space Station for peaceful purposes, in accordance with international law. 13)

- In 1998 the PDR (Preliminary Design Review) of Columbus was done on schedule. This lead to the start of CDRs (Critical Design Reviews) for equipment and subsystems. Interfaces were defined with NASA between Columbus and the Shuttle, the overall ISS and the payload racks which house, for example, the Columbus experiment facilities.

- On March 31, 2003 ESA signed a contract with DLR to develop the Columbus Control Center at the German Aerospace Center in Oberpfaffenhofen. Under this contract DLR is responsible for the development and integration of the CCC including the operations of the European ground infrastructure on behalf of ESA. DLR took also responsibility for management of the center and to coordinate and support all on-orbit operations of the Columbus laboratory on behalf of ESA.

- In July 2004, ESA signed an ISS exploitation agreement with EADS-Astrium (formerly EADS Space Transportation). The contract covers initial exploitation activities, in particular preparations for the operations of Columbus. Regarding the initial exploitation activities, the contract dealt with the European experiment facilities for the ISS as well as with the experimental program to be executed by the astronauts onboard the Station. The contract also covers activities in the fields of the European flight control team and crew training, ground facility maintenance and engineering support for Columbus. - Part of the contract included the production of the ATVs (Automated Transfer Vehicles), the European spacecraft, which will act as an ISS cargo ship, and further be used for reboosting the ISS to higher orbital altitudes to counter the effects of atmospheric drag and remove waste from the station.

- Columbus payload rack agreement: ESA signed a hardware exchange agreement with JAXA (former NASDA) of Japan. Within the framework of this MOU, JAXA provided ESA with 12 International Standard Payload Racks (ISPRs) for use in the Columbus laboratory on the ISS. In exchange, ESA provided JAXA with one MELFI (Minus Eighty degree Celsius Laboratory Freezer for ISS) system, identical to those developed by ESA for NASA, in the context of the early utilization MOU (Ref. 9). 14)

The construction of the Columbus module was done by the European industry with EADS-Astrium as prime contractor. After being assembled in Bremen, Germany, the Columbus module was transported to the Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, FLA, USA on May 27, 2006, aboard a Beluga Airbus. 15)

The launch of Columbus was initially planned for late 2004, but the catastrophic disintegration of the US Space Shuttle Columbia over Texas on February 1, 2003 delayed deployment by more than three years.

Internal Experiments

The Columbus module is pressurized providing a laboratory environment for up to three astronauts.

• Biology facility: WAICO (Waving and Coiling of Arabidopsis Roots), testing of the effect that gravity has on the spiralling motion (circumnutation) that occurs in plant roots. 16)

• EMCS (European Modular Cultivation System), an ESA experiment facility dedicated to biological investigations in weightlessness.

• Geoflow-2, is an experiment of the FSL (Fluid Science Laboratory) rack of Columbus. Investigation of the flow of an incompressible viscous fluid (silicone oil) held between two concentric spheres. It is considered of importance in such areas as flow in the atmosphere, the oceans, and the movement of Earth's mantle on a global scale as well as other astrophysical and geophysical problems having spherical geometry flows shaped by rotation and convection. - The Geoflow-2 experiment was brought to space with ATV-2 (launch Feb. 16, 2011) and installed in the FSL rack on 27 February 2011.

• Human physiology: The objective of the project is to demonstrate the efficiency of this technique as an early detection of impairment in bone remodelling and ultimately to provide information on the mechanics underlying bone loss and to accurately evaluate the efficiency of relevant countermeasures.

• Chromosome-2: Study of chromosome changes and sensitivity to radiation in lymphocytes (white blood cells) of ISS crew members.

• Neocytolysis (selective destruction of young red blood cells): This experiment covers the effects of weightlessness on the hemopoietic system: the system of the body responsible for the formation of blood cells.

• Radiation dosimetry experiment ALTCRISS (Alteino Long Term monitoring of Cosmic Rays on the International Space Station) is an ESA experiment to study the effect of shielding on cosmic rays in two different and complementary ways.

Note: The list of internal facilities is incomplete.

Mission Operations

The Columbus module can accommodate 4 ISPRs (International Standard Payload Racks) in a row and a total of 10 P/L (Payload ) racks. According to agreements, five P/L ISPRs can be utilized by ESA and 5 by NASA.

All resources for operating Columbus are provided by the Station (ISS). Power is provided at a voltage of 120 V and distributed and converted by the Columbus Electrical Power Distribution system. Nitrogen is provided by the Station as well and distributed by the ECLSS (Environmental Control and Life Support System) of Columbus to the 10 ISPRs and the Columbus TCS (Thermal Control System). 17)

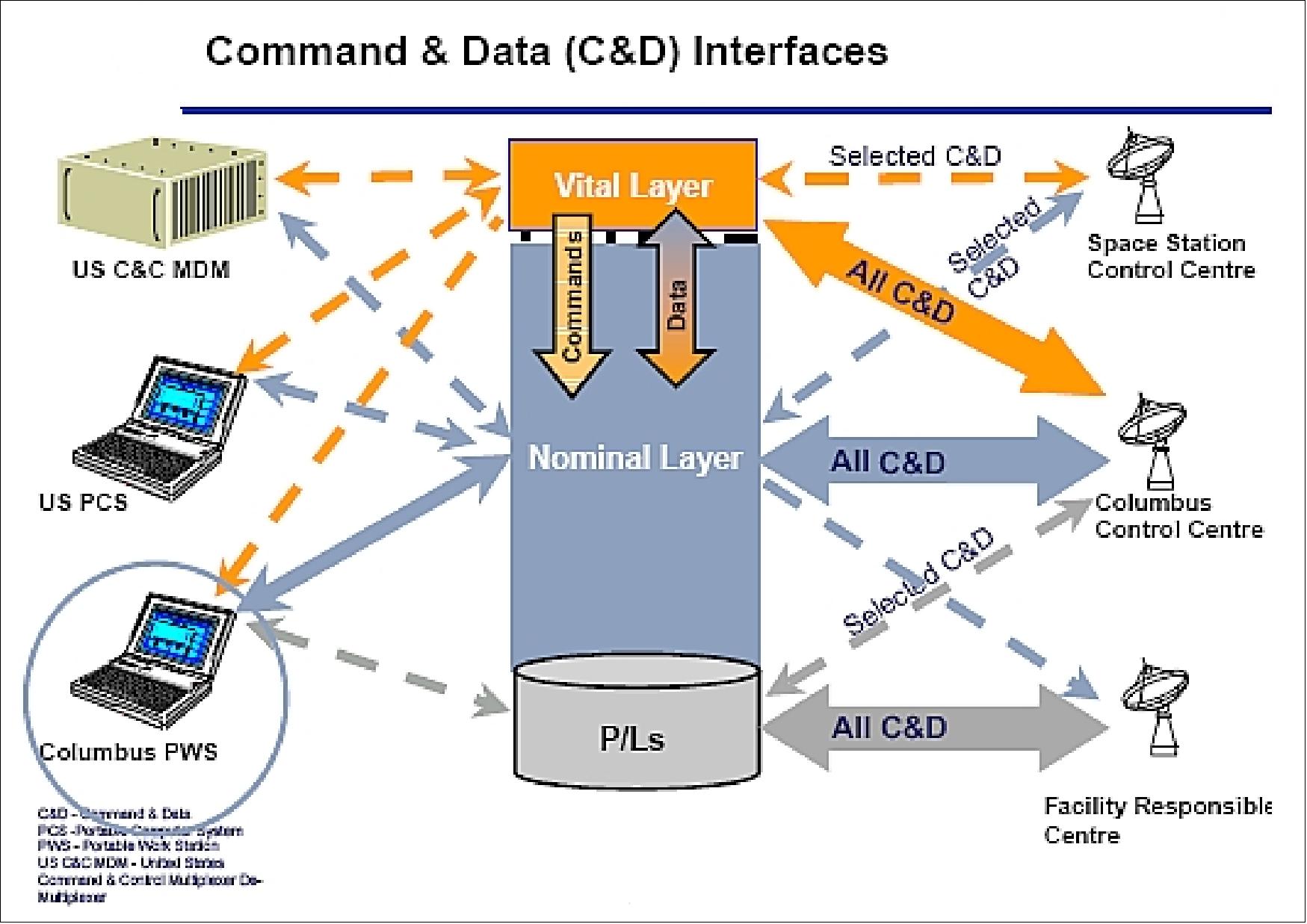

Furthermore, respiratory air is delivered to the Columbus ECLSS and water for cooling to the Columbus TCS. Columbus also provides voice and video services to the crew via its COMMS (Communication System). Downlink and uplink of data and commands is provided by Station. All the commanding and monitoring of the Columbus systems and P/Ls is managed by the Columbus DMS (Data Management System).

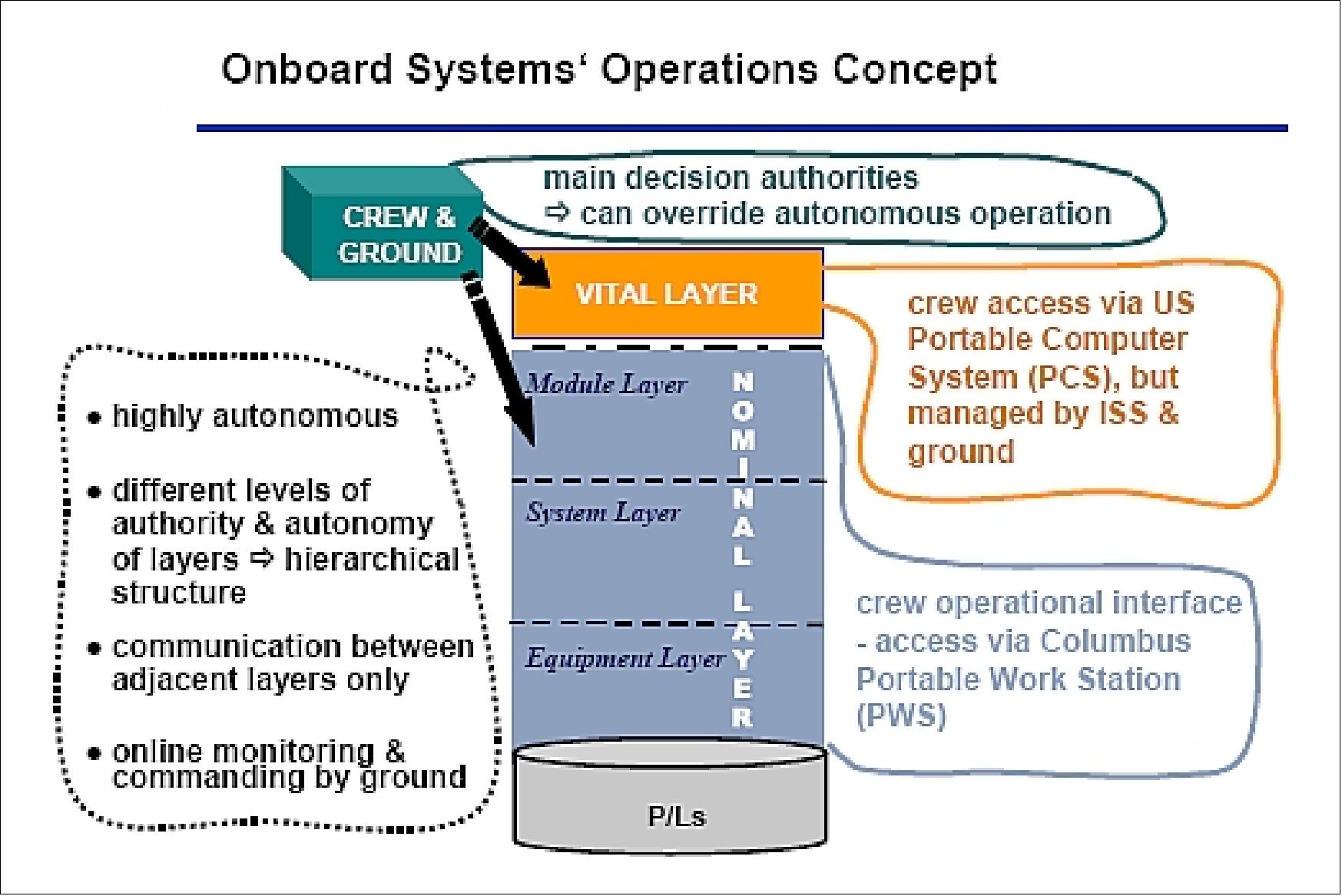

The crew can operate the systems and potentially the P/Ls via a station common laptop configured with Columbus specific software - the Columbus PWS ( Portable Workstation). For certain vital tasks, the crew has to use a US PCS (US Portable Computer System) laptop.

The DMS is comprised of two different types of layers: the vital layer and the nominal layer. The crew can access the vital layer via the US PCS and the nominal layer via the Columbus PWS. The vital layer is mainly dealing with safety relevant issues and communicating with the US Orbital Segment (OS). The nominal layer, which is the interface for the crew for operating Columbus systems, can be subdivided into 3 more layers: the module layer, the system layer and the equipment layer. Each layer has a certain task, authority and autonomy (Figure 8).

The module layer of the nominal layer assures that all Columbus systems and P/Ls operate smoothly and do not interfere with each other. The system layer can be interpreted as smart H/W of the systems. This layer commands and controls system instrumentation directly by dedicated system S/W. Each system is responsible for command & control of its own H/W and processes. - The equipment layer comprises all the items which are actually implementing the operation of the systems. The items in this layer act on all the commands from the crew and the ground.

The nominal crew I/F for the operation of Columbus is the Columbus PWS which is communicating with the nominal layer. The vital layer is only accessed in case of off-nominal situations, like an emergency.

The commanding of Columbus is the task of the Columbus CC (Col-CC) - for all nominal and off-nominal operation scenarios. All system operations will be carried out by on-line control. During normal operations they supervise on-board activities and uplink updates to the configuration data tables.

Sensor Complement

CEPF (Columbus External Payload Facility) provides four attachment sites for un-pressurized payloads (i.e. platforms to accommodate external payloads). The overall objectives of the external payloads are related to applications in the field of space science, Earth observation, technology demonstrations, and innovative sciences from space. CEPF features two identical L-shaped consoles attached to the starboard cone of the Columbus module in the zenith (top) and nadir (bottom) positions, where each console is supporting two platforms for external payloads or payload facilities. In total, four external payloads (payload facilities) can be operated at the same time (Figure 4).

The following external payloads are described in separate files on the eoPortal: EuTEF, SOLAR, ACES, ASIM and ColAIS; hence, the payloads are simply enumerated here for completeness (Ref. 16). 18) 19)

• EuTEF (European Technology Exposure Facility): launch Feb. 7 2008 on STS-122. EuTEF is comprised of the following sub-experiments:

- DEBIE-2 (DEBris In orbit Evaluator)

- DOSTEL (DOSimetric radiation TELescope)

- EuTEMP (EuTEF Thermometer)

- EVC (Earth Viewing Camera)

- EXPOSE (Exposure Experiment)

- FIPEX (Flux (Phi) Probe EXperiment - Time resolved Measurement of Atomic Oxygen)

- MEDET (Material Exposure and Degradation Experiment)

- PLEGPAY (Plasma Electrical Grounding Payload)

- TriboLab (Tribology Laboratory).

Note: After a successful mission of 1.5 years in open space, the EuTEF platform has been returned to Earth with the Shuttle 17A (STS-128) mission on Sept. 11, 2009.Throughout its 18 months in space, EuTEF has been under the continuous control of the Erasmus USOC (User Support and Operations Center) at ESA/ESTEC.

• SOLAR (Solar Monitoring Observatory): launch Feb. 7 2008 on STS-122.

SOLAR is an ESA experiment package consisting of three science instruments, namely SOVIM (Solar Variability and Irradiance Monitor), SOLSPEC (Solar Spectral Irradiance Measurements), and SolACES (Solar Auto-Calibrating EUV/UV Spectrophotometers). The overall objective is to measure the solar spectral irradiance with unprecedented accuracy.

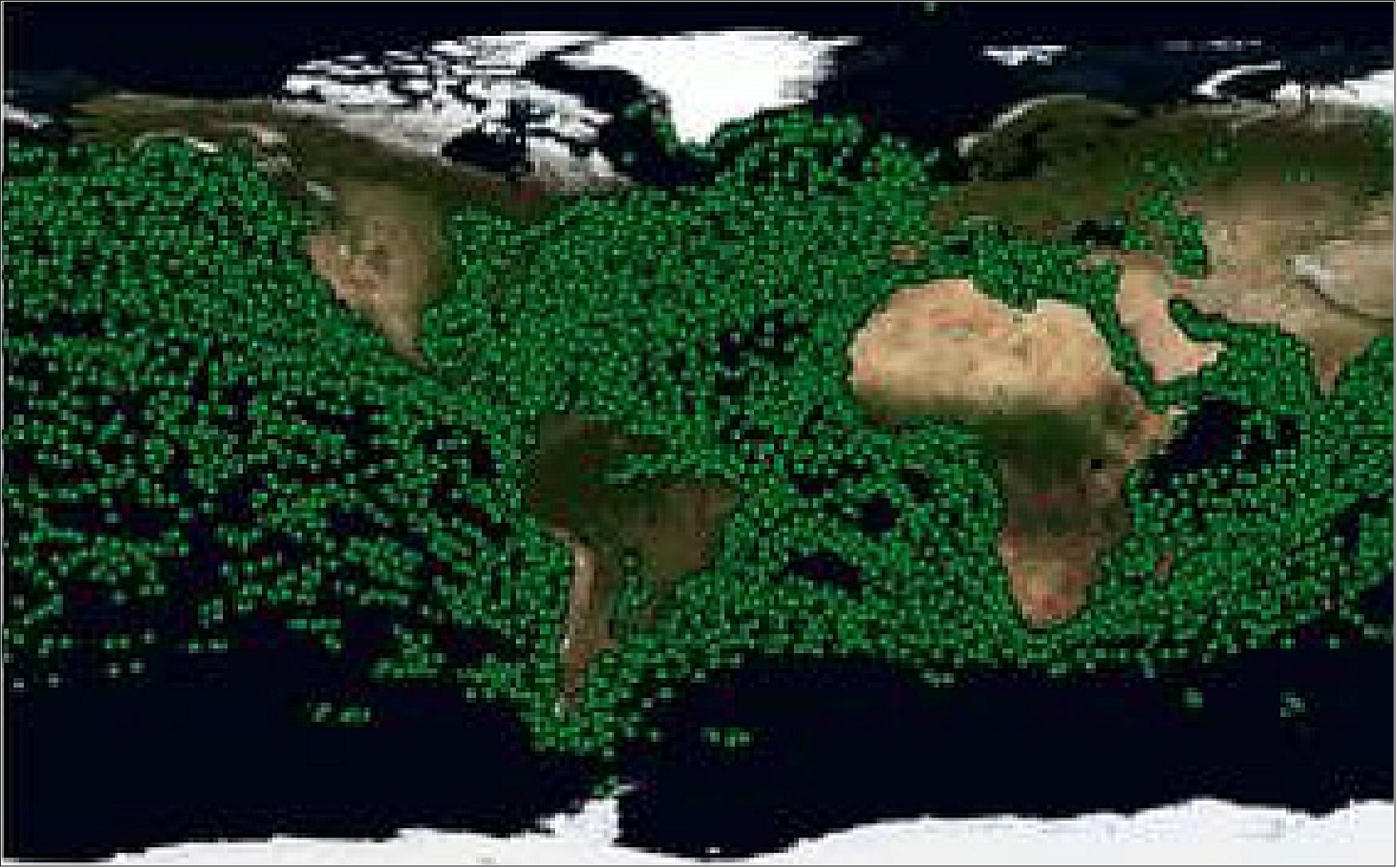

• ColAIS (Columbus Automatic Identification System): Both receivers of ColAIS (NorAIS and LuxAIS) were delivered to the Columbus module of ISS by Japan's HTV-1 supply ferry in September 2009 (launch Sept. 10, 2009 from TNSC, Japan; docking of HTV-1 on Sept. 23, 2009). 20) 21)

Both AIS receivers are designed for wide-area vessel detection on the oceans in VHF frequency. The aim is to demonstrate spaceborne ship monitoring techniques which can then serve as the basis of operational services via satellite constellations.

• ASIM (Atmosphere-Space Interactions Monitor): A launch of ASIM is planned for 2013 on the HTV (H-II Transfer Vehicle), the automated unmanned transport system developed by JAXA as cargo transportation system for the International Space Station.

The objective of ASIM is to observe TLEs (Transient Luminous Events) that occur in the Earth's upper atmosphere accompanied by thunderstorms in the lower atmosphere.

• ACES (Atomic Clock Ensemble in Space): A launch of ACES is planned for the timeframe 2015-16 on the HTV (H-II Transfer Vehicle) of JAXA. 22)

ACES is an ESA ultra-stable clock experiment, a time and frequency mission to be flown on the Columbus module of the ISS (International Space Station), in support of fundamental physics tests. The mission objectives are both scientific and technological and is of great interest to two main scientific communities: 23)

- The Time and Frequency (T&F) community; which aims to use ACES as a tool for high precision Time and Frequency metrology

- The Fundamental Physics community; which will benefit from the use of ACES data for accurate tests of general relativity.

Data and Communications

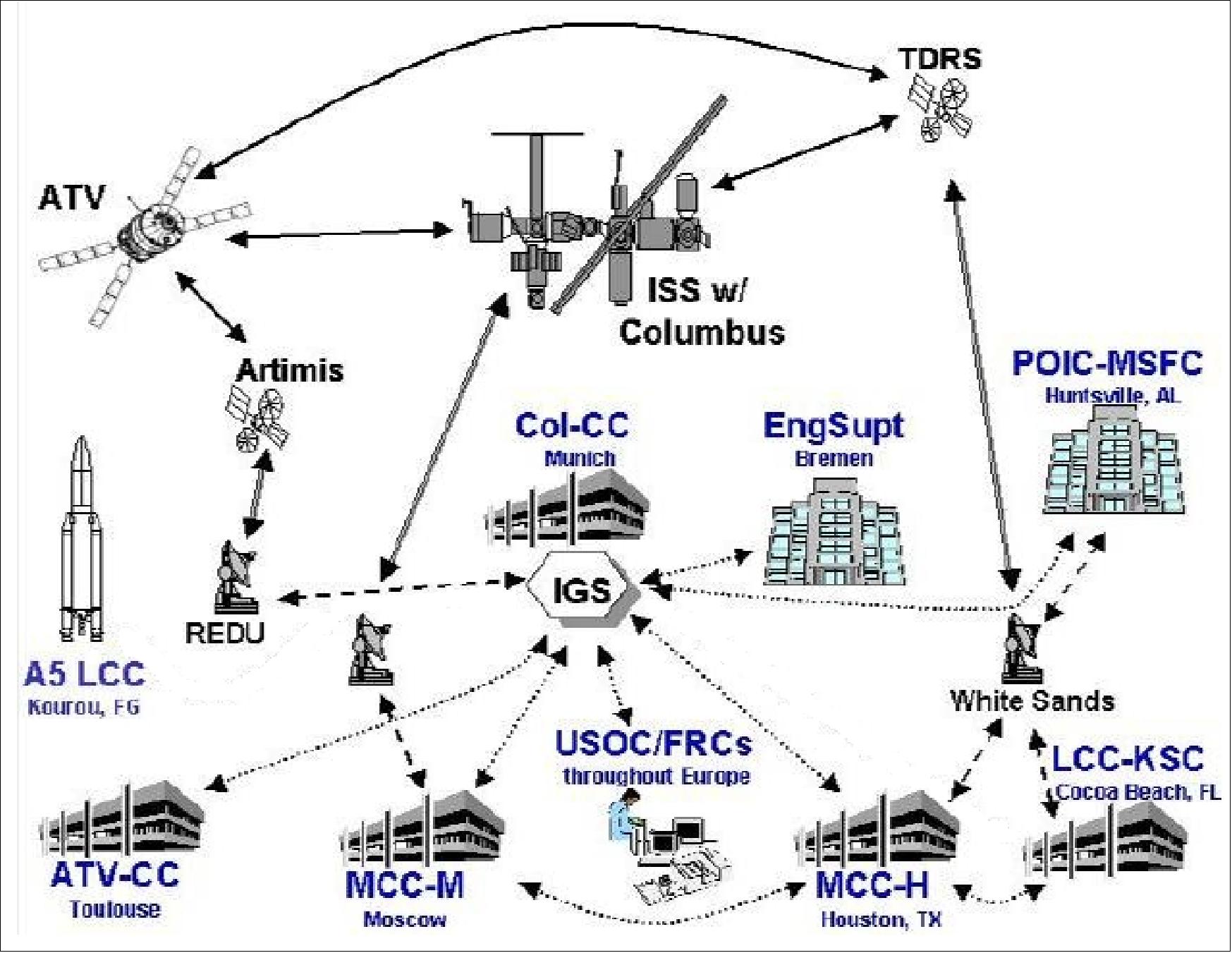

The Columbus module payloads are being operated by the Col-CC (Columbus Control Center), located at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) in Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany. Under the call sign 'Munich', Col-CC is responsible for all Columbus systems and for European science activities on board the ISS. Col-CC control teams began their operational activities as a precursor to Columbus operations during ESA's Astrolab mission to the ISS in 2006. 24) 25)

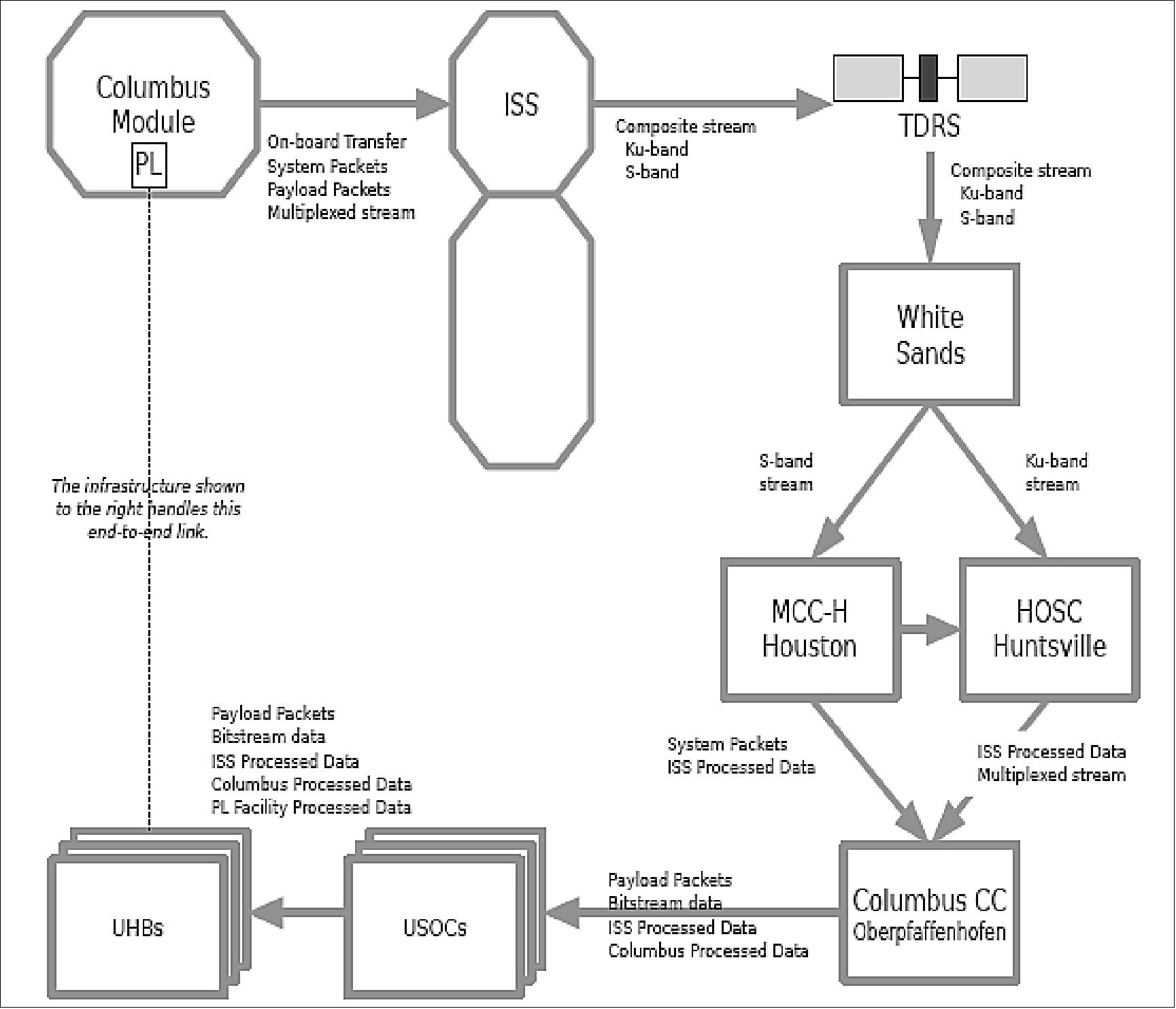

Data communications: In Figure 10, it can be seen that the data undergoes many transformations on its trip from a payload on the Columbus module to the end user at a UHB (User Home Base). These transformations are necessary to fit the different data types, with their associated frequency, visibility and criticality requirements into the main ISS downlink and ground data distribution system.

A single measurement can show up in many different places and in many different forms. For example, a payload temperature sensor measurement that is considered safety critical and must be monitored in several places, could be included into the Columbus data system so that it can be monitored by the Columbus on-board computers. It could also be required to be in the on-board transfer of data from Columbus to the ISS, so that it can be monitored there on location. This one measurement could therefore be included in a payload CCSDS packet, a Columbus system CCSDS packet, an ISS CCSDS packet, MCC-H (Mission Control Center-Houston) processed data, Col-CC processed data, and USOC (User Science Operation Center) processed data. 26)

In general, science data in not transmitted via the TRDS S-band composite stream, which has a much lower bandwidth than the Ku-band stream, and is reserved for ISS and Columbus system data required to ensure the health and continued operation of the onboard systems. An exception to this is that payload command response packets (CCSDS format) are routed through the S-band link. This is primarily due to the fact that commands can only be linked through the S-band link. Since the S-band and Ku-band, although using the same relay satellite, have different communication coverage, it is necessary to rout the command responses (including payload command responses) through the same link to ensure that these differences do not cause ground centers to loose feedback on commands uplinked.

Data handling at USOCs: ESA has adopted a decentralized scheme for the handling of European payloads on board the Station. USOCs are required to handle the majority of tasks related to the preparation for and the in-flight operation of the multi-user facilities. The USOCs are based in national centers distributed throughout Europe. These centers are responsible for the use and implementation of European payloads on board the ISS.

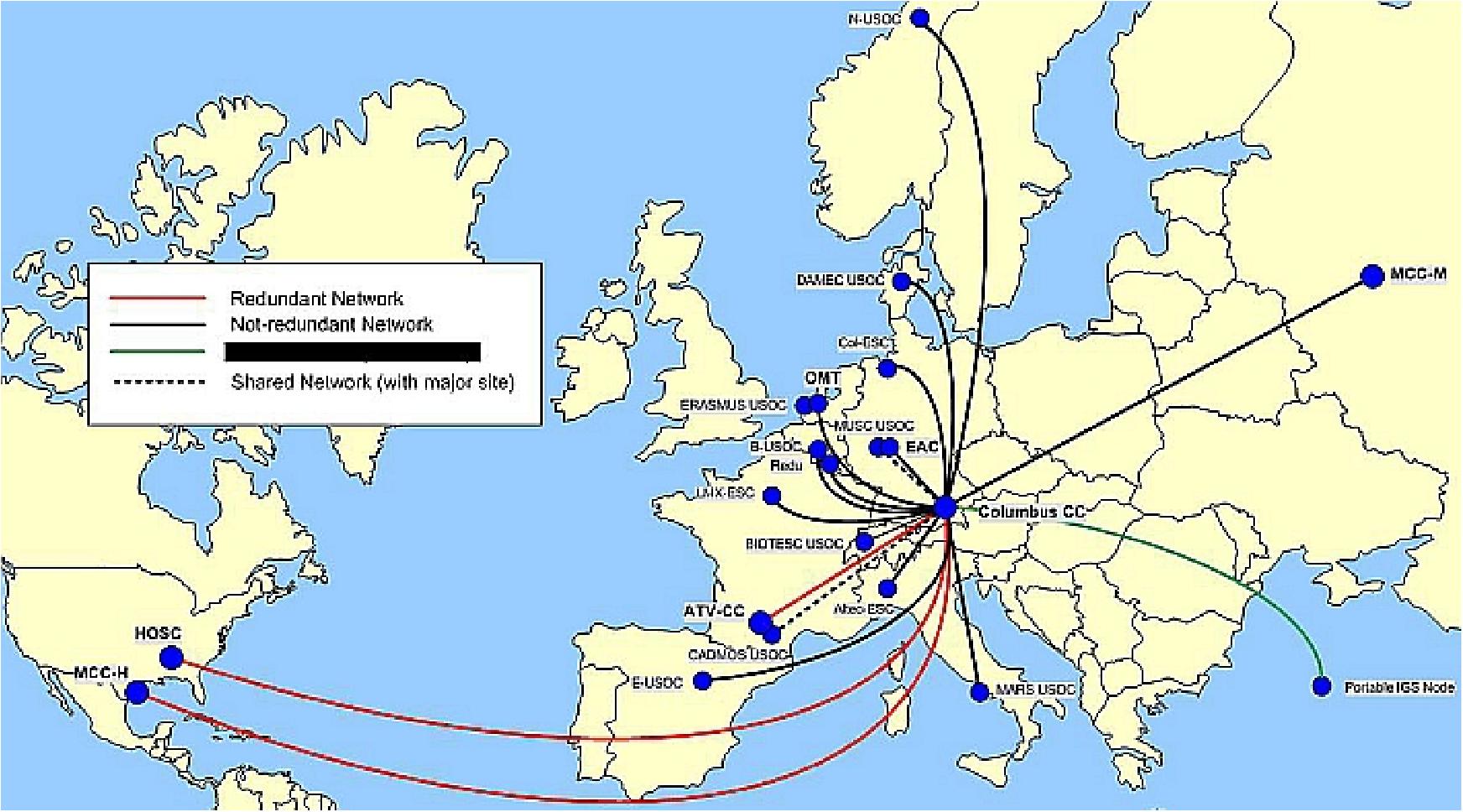

The Col-CC, integrated in GSOC and responsible for the operation of the Columbus space and ground segment, uses the IGS (Interconnection Ground Subnetwork). This network provides the basis for communication between Col-CC and its international partners (NASA, ESA, ATV-CC, etc.) and all USOCs across Europe. The IGS network was originally designed to use ATM technology, but due to cost reductions, many centers were connected via ISDN (Integrated Services Digital Network). Since 2009, the ATM (Asynchronous Transfer Mode) and ISDN technology was replaced by the MPLS (Multiprotocol Label Switching) network. The migration from ATM/ISDN to MPLS implied a lot of configuration and testing work within the IMS in parallel to real-time operations. 27) 28)

In the ATM/ISDN network, the IMS was configured to monitor the ATM/ISDN connections and to start/stop the ISDN lines towards the remote user centers (USOCs) to keep the costs under control. In the MPLS network the main focus is on monitoring the IGS network since start/stop of connections is not necessary anymore.

The ground segment has a star-like topology with a central node at Col-CC. Figure 11 gives an overview of the Columbus ground segment. In the design phase of the Col-CC, it was decided not to control and monitor every subsystem separately from its own console, but to integrate the management of the various subsystems under a single umbrella management subsystem - the IMS (Integrated Management System). This is a customized software designed to support the daily work of Ground Controllers (GCs) and System Controllers (SysCons) at Col-CC.

Mission Status

• April 27, 2023: The International Space Station (ISS) partners have agreed to extend the operational period of the ISS. The United States, Japan, Canada and participant European Space Agency (ESA) countries will support operations until 2030, while Russia has committed to continuing station operations until 2028. 61)

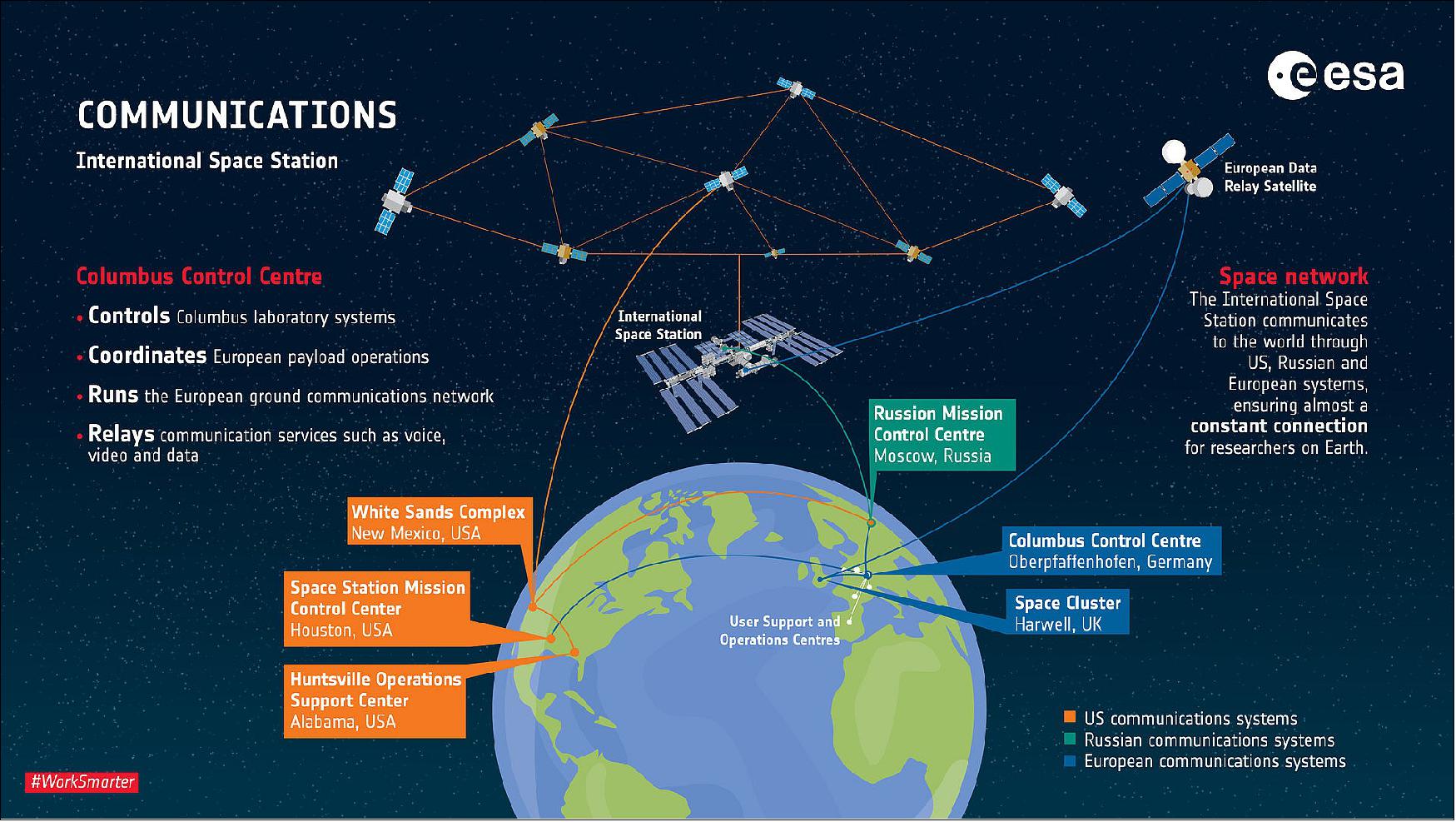

• January 17, 2022: Space Station communications infographic. — Aside from using the Russian and NASA communication systems. astronauts on board the International Space Station are now connecting straight to Europe at light speed, thanks to the European Data Relay System (EDRS). The satellite picks up signals from the Station as it loops around the Earth every 90 minutes and relays them straight back to its European base station — ESA's Columbus Control Centre at DLR in Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany. 31)

- The state-of-the-art system provides speeds of up to 50 Mbit/s for downlink and up to 2 Mbit/s for uplink. The communications device which enables it – nicknamed ‘ColKa' for ‘Columbus laboratory Ka-band terminal' – was installed during a spacewalk in January 2021.

- The Airbus' SpaceDataHighway – developed with the support of ESA – provides broadband connectivity services between the International Space Station and the Earth. With the Columbus Ka-band (ColKa) terminal now installed and fully tested on-board the ISS, a SpaceDataHighway satellite will start to relay data via a bi-directional link in real time between the ISS Columbus Laboratory and the Columbus Control Centre located at the German Aerospace Center DLR near Munich as well as research centres across Europe. 32)

- Thanks to the SpaceDataHighway and the ColKa terminal, ESA will benefit from a direct and sovereign access to the ISS, thus increasing the operational flexibility allowing more astronauts, scientists and researchers to benefit from a direct link with Europe. This will also enable ESA to create slots for ad-hoc experiment access and interaction with European astronauts.

- The ColKa data service provision has been contracted between ESA and Airbus. As part of this new SpaceDataHighway service, Airbus has adapted its Ka-band inter-satellite link to ensure data will be channelled via the ground station at Harwell Campus, UK.

- Besides this Ka-band service, the SpaceDataHighway is the world's first laser communication geostationary constellation. It represents a game changer in the speed of space communications, using cutting-edge laser technology to deliver secure data transfer services in near-real time. The system has achieved more than 50,000 successful laser connections within the first five years of routine operations.

- Its satellites can connect to ISS as well as low-orbiting observation satellites at a distance of up to 45,000 km. From its position in geostationary orbit, the SpaceDataHighway system relays in near real-time to Earth the collected data, a process that would normally take several hours. It therefore enables the quantity of image and video data transmitted by observation satellites to be greatly increased and their mission plan can be re-programmed at any time and in just a few minutes.

• October 10, 2019: The International Space Station is open for business and ESA is calling on industry to help extend the capabilities of Europe's Columbus laboratory to support science and technology in space beyond 2024. 33)

- Columbus is Europe's single largest contribution to the International Space Station. Launched in 2008, it is the first permanent European research facility in space.

- The laboratory has supported over 185 science and technology demonstrations to date, many of which are operated remotely from ESA's Columbus Control Center in Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany.

- With the lifetime of the Station expected to be extended until 2030, there is now an opportunity to modernize and enhance the lab's capabilities – starting with an industry workshop at ESA's technical heart ESTEC in Noordwijk, The Netherlands in November.

- Head of ESA's astronaut center (EAC) Frank De Winne says the modernization of Columbus over the next 10 years creates room for greater commercial involvement, allowing Europe to achieve even more in orbit while freeing up public funds for investment in future space exploration to the Moon and Mars.

- "The extension of Space Station operations is a positive step in ESA's work to increase space access for European researchers and boost industry capability Europe-wide," he explains.

- "By opening a call to industry to contribute innovative solutions for Columbus upgrades both in space and on the ground, we build on current commercial initiatives, such as the ICE Cubes facility installed in Columbus in 2018, the Bartolomeo platforms for external payloads and the new Bioreactor Express Service, and complement international efforts to further develop a truly competitive low-Earth orbit economy."

- When it comes to the Columbus upgrades, ESA sees industry playing a leading role in the provision of solutions that target both institutional requirements and commercial needs. These include upgrades to data storage, processing, management and transfer both on ground and in space as well as new facilities and capabilities for the Space Station. Companies will also have the opportunity to provide services to commercial customers.

- When it comes to the Columbus upgrades, ESA sees industry playing a leading role in the provision of solutions that target both institutional requirements and commercial needs. These include upgrades to data storage, processing, management and transfer both on ground and in space as well as new facilities and capabilities for the Space Station. Companies will also have the opportunity to provide services to commercial customers.

- "European industry must prepare for the future of the global space service market. US companies are already establishing a presence in Europe, but we know we have the skills and knowledge here. I cannot wait to see what Europe comes up with as we embark on the next phase of exploration and discovery," Frank says.

- The initial industry workshop will inform space and non-space companies about ESA's Columbus requirements.

• February 19, 2019: Europe's Columbus laboratory enters its eleventh year in space with steady operations, a few upgrades and several experiments in full swing. 34)

- The physical behavior of particles, liquids and cells in microgravity was the focus of ESA's activities on the International Space Station during the first weeks of February.

- The three astronauts from Expedition 58 living in space worked on experiments about how time perception and their biological clocks might change in space. While awaiting the arrival of three new crewmates on 14 March, the trio is carrying out a significant amount of science.

Liquids in Space

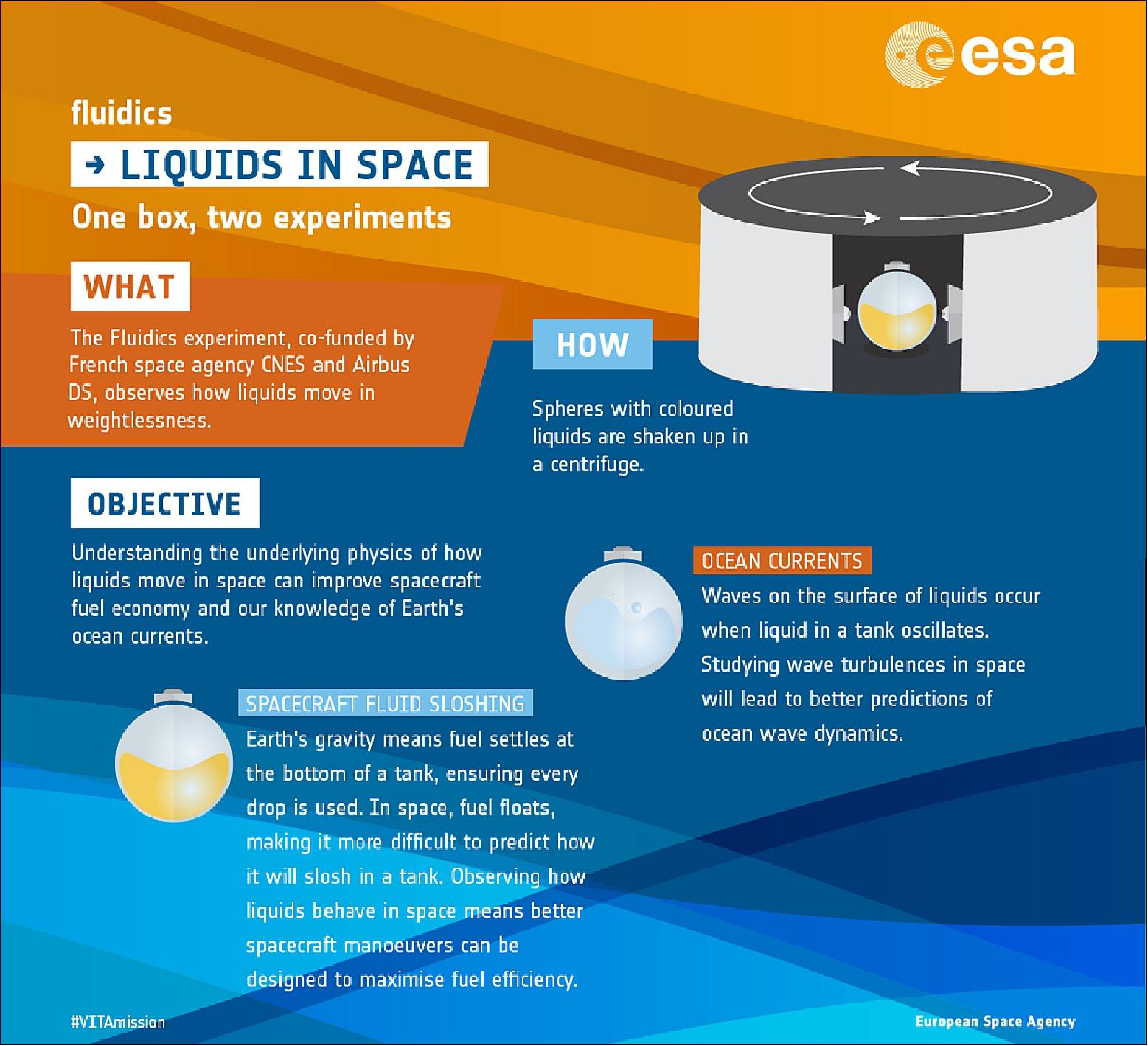

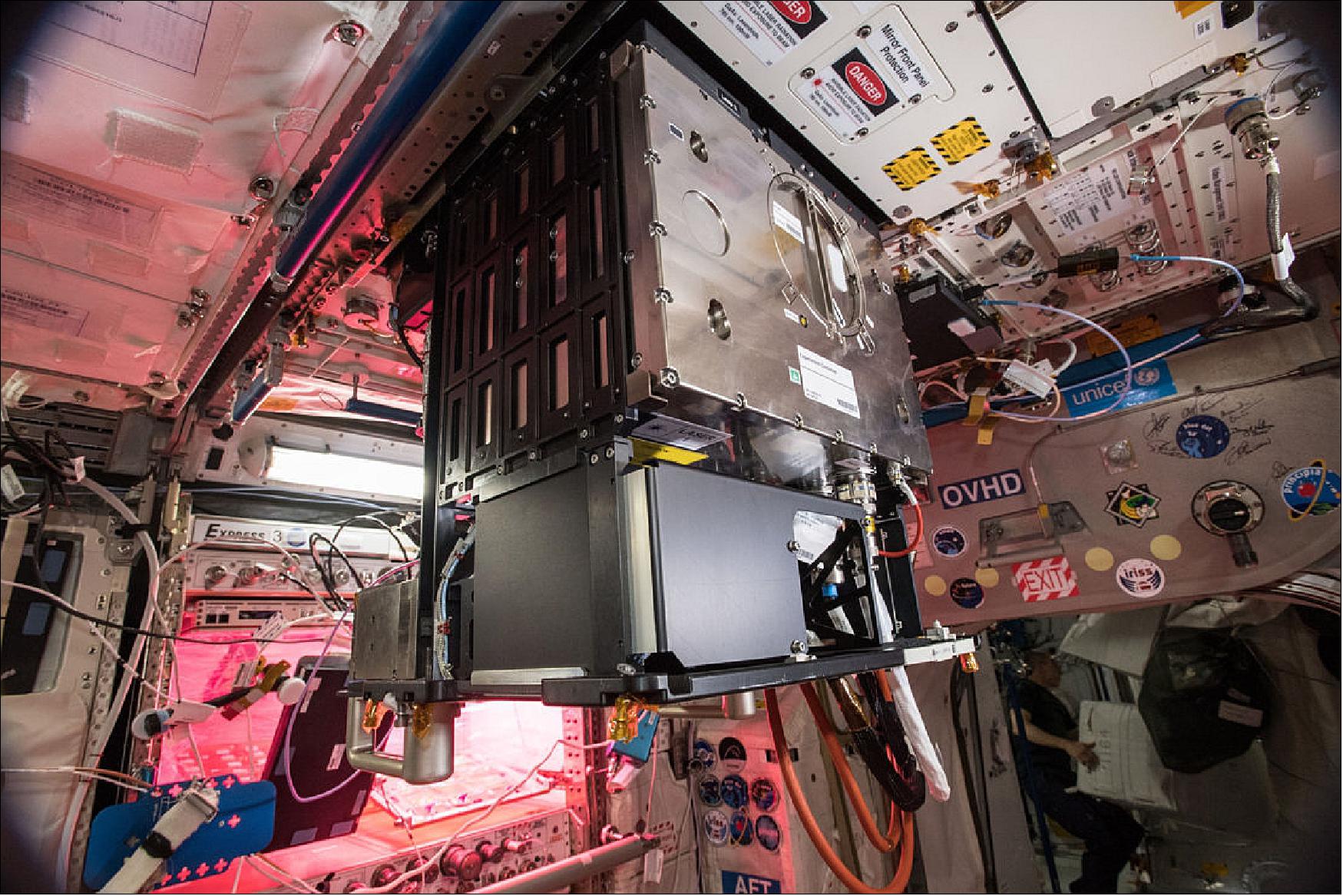

- The Fluidics experiment, or Fluid Dynamics in Space, observes how liquids move in weightlessness (Figure 15).

- To help in the quest to learn more, the astronauts installed hardware in the Columbus laboratory and turned on a miniature centrifuge to start the fifth science run of this experiment.

- Gravity on Earth means fuel settles to the bottom of a fuel tank so it is easy to ensure every drop is used. In space, fuel floats, making it more difficult to predict how it will slosh around inside a fuel tank.

- With Fluidics, researchers hope to understand the underlying physics of how liquids move in space so we can improve spacecraft fuel economy.

New Electronics for Kubik

- One of the longest-running experiment units running on the Space Station got an upgrade earlier this month. Two Kubik units now have new electronics that will allow science teams on ground to teleoperate the equipment and check how the system is running as well as download data with just a few clicks.

- These features will help keep Kubik operational into its second decade of space research. Kubik – from the Russian for cube – is a small incubator designed to run autonomously and study biological samples in microgravity. Seeds, stem cells, fungi and even swimming tadpoles have been hosted in separate tissue-box-sized units.

Stability in Orbit

- The Fluid Science Laboratory, stationed in the Columbus module, allows researchers to study how foams, emulsions and materials behave in the absence of gravity.

- The Soft Matter Dynamics experiment, ran to investigate foams that are hard to study on Earth as convection destabilizes the foams.

- The study of foams and emulsions in weightlessness have wide practical applications. Solidified metal foams, for example, can be as strong as solid metals but are much lighter, so they are used in advanced aerospace technology and manufacturing as well as modern consumer cars.

- The Compacted Granulars experiment, also known as CompGran, monitored the behavior of plastic grains until they reach complete arrest. Granular particles are far from equilibrium and lose energy when colliding with each other. Scientists carrying out this research are looking at the granular materials without the rapid sedimentation that occurs on Earth as they are unaffected by weight differences.

Space Rhythm and Time

- Our bodies know roughly what time of day it is, making us feel sleepy at night. Astronauts experience 16 sunrises and sunsets every day on the International Space Station as it circles Earth, making it a unique place to study how their biological clocks cope.

- Long-duration spaceflights probably affect the inner clock in humans due to changes of living in light-dark cycle that does not correspond with the 24-hours of a day on Earth.

- NASA astronaut Anne McClain completed her third session for the Circadian Rhythms experiment that is investigating this phenomenon. For 36 hours, she wore two sensors strapped to her forehead and chest to monitor body temperature. The experiment will also measure her melatonin levels, a hormone linked to sleep.

- As part of the Time Perception experiment, Anne and Canadian Space Agency astronaut David Saint-Jacques wore a headset to block out external visual cues and gauged how long a visual target appears on a laptop screen. Their reaction times will help understand why and how time perception is altered in orbit.

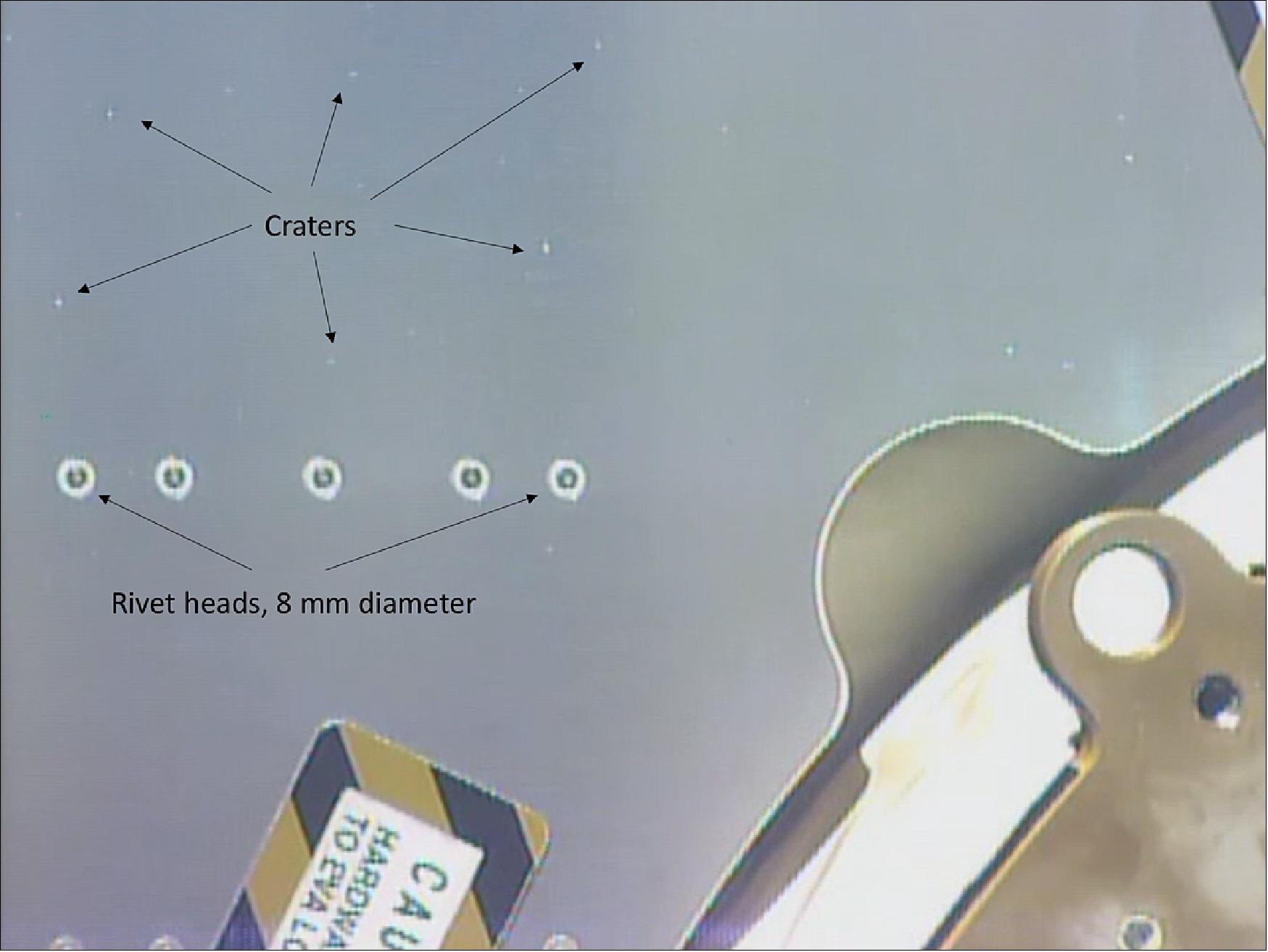

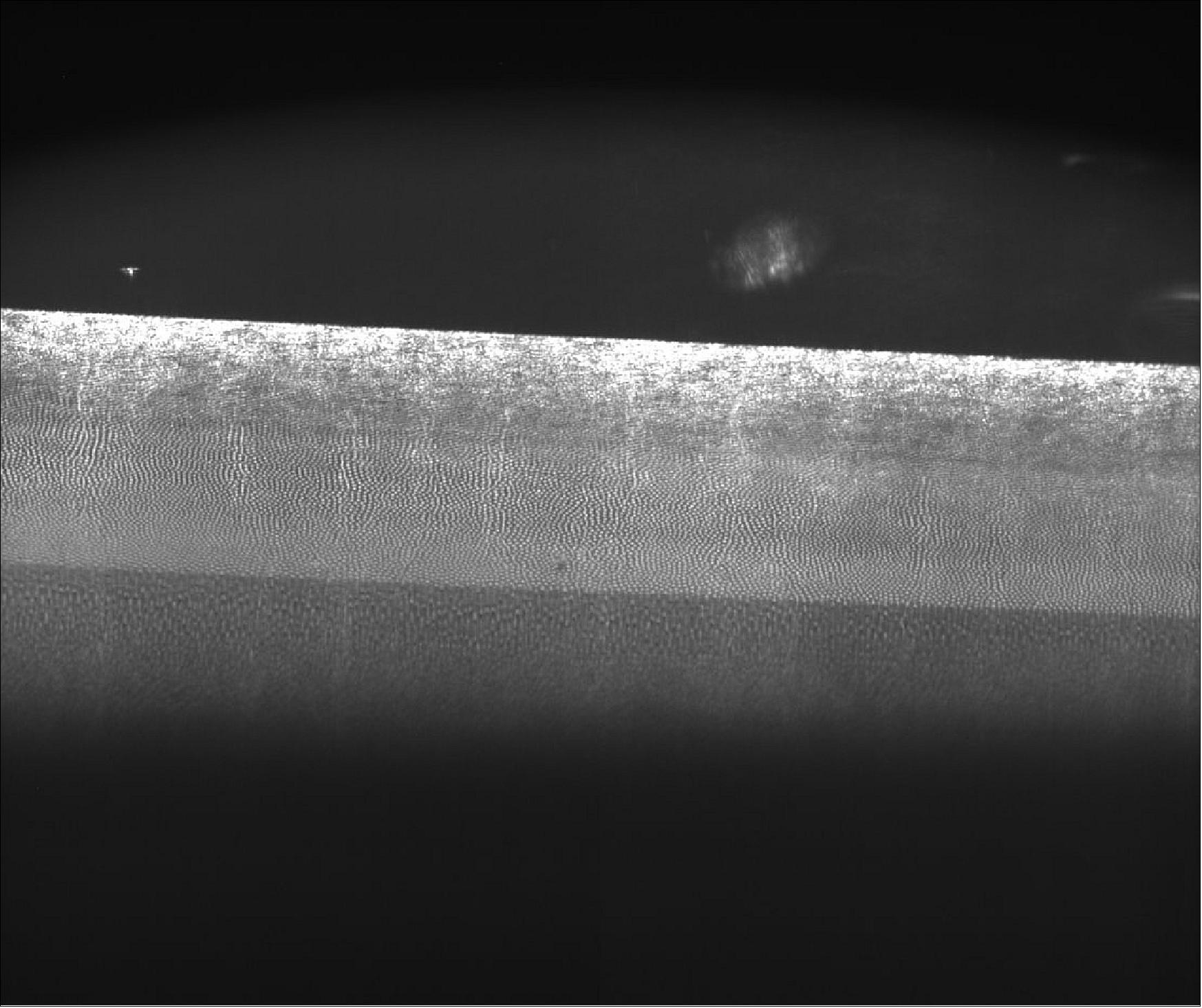

• January 23, 2019: The Columbus module received an inspection of its outer hull. On 6 September 2018, the 17-meter arm, Canadarm2, attached to humankind's most distant outpost began to move. Its instructions were to survey the spaceship's European science laboratory for signs of impact damage from marauding bits of space rock or space debris. 36)

- The robotic arm camera on the International Space Station has now completed the first two scans of the outer panels of the Columbus module, in search of micro impact 'craters'.

- The Columbus crater survey was requested by a European team of scientists, including Detlef Koschny, an expert from ESA's Planetary Defence Office focussing on space safety and security.

- "Space is vast and mostly empty, but small space rocks are constantly passing into our local environment as well as debris from past spacecraft collisions and explosions", explains Detlef.

- The Columbus module, part of the International Space Station, is the first permanent European research facility in space, and the largest single contribution to the Station made by the ESA.

- Launched in February 2008, the European Columbus laboratory has been in space for ten years, but until September it had not been thoroughly checked for signs of impact damage.

- In their first analysis of the data, the team found several hundred small impact craters, visible in the image of Figure 19 as tiny dents in the laboratory's outer casing. These would have been produced by very small pieces of either natural or artificial debris, typically smaller than 1 mm in size.

- "These fragments can travel at extremely fast speeds, and if larger than a centimeter in size could do a great deal of damage to the Space Station and satellites in orbit", Detlef continues.

- As was recently discovered on the Station, even a small hole in the protective casing of the Soyuz module created a noticeable loss of air pressure. This recent discovery is now thought not to be the result of an external impact, but it shows the importance of understanding how these events can happen.

- Detlef concludes, "These little dents in the outer part of the Columbus module show how the space around Earth is not so empty after all. They also show what a good job the ESA-built module is doing to protect astronauts living and working in space".

- This study allows the team to better understand the density of human-made debris particles at the orbital altitude of the Space Station, in comparison to the natural micrometeorite density near Earth, both of which are important for constructing models to help us understand the risks of the meteorites marauding through space.

- The recordings will also be used by ESA's Space Debris Office, who are evaluating the footage in order to characterize the craters found – an important tool for validating current models, such as ESA's Meteoroid and Space Debris Terrestrial Environment Reference (MASTER), which describes the impact risk to missions in orbit from human-made and natural debris.

- This project was proposed by Gerhard Drolshagen (University of Oldenburg, D), Robin Putzar (Fraunhofer/EMI, Freiburg, D), Dieter Sabath (DLR Oberpfaffenhofen, D), and Detlef Koschny (ESA) plus other experts from TU Braunschweig, D, ESA, and NASA.

• February 7, 2018: One space lab, five spacecraft, 10 years of success. A decade ago, the Columbus laboratory set sail for humanity's new world in space. 37)

- Shortly afterwards, the first Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) arrived at the International Space Station as the most reliable and complex spacecraft ever built in Europe.

- The event was a unique opportunity to re-live some exciting milestones, connect live to the Station and look into space exploration plans.

• February 6, 2018: The date has finally arrived. On 7 February 2008, after years of planning and construction, delays and bad news, concessions and coordination, Columbus is ready to go. 38)

- Loaded inside Space Shuttle Atlantis, Europe's largest contribution to the International Space Station is about to make its final journey.

- All tests are complete, the crew is ready and the weather has been cleared for liftoff. In less than an hour, Columbus and the seven-strong crew will begin the ride of their lives, at 19:45 GMT, from pad 39A at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, USA.

- Fast forward 10 years to the present, and we are one day away from marking this historic moment for European space research.

- Tomorrow, the larger Columbus family of planners, builders, scientists, support teams and astronauts will gather to celebrate the laboratory at ESA's technical heart in the Netherlands.

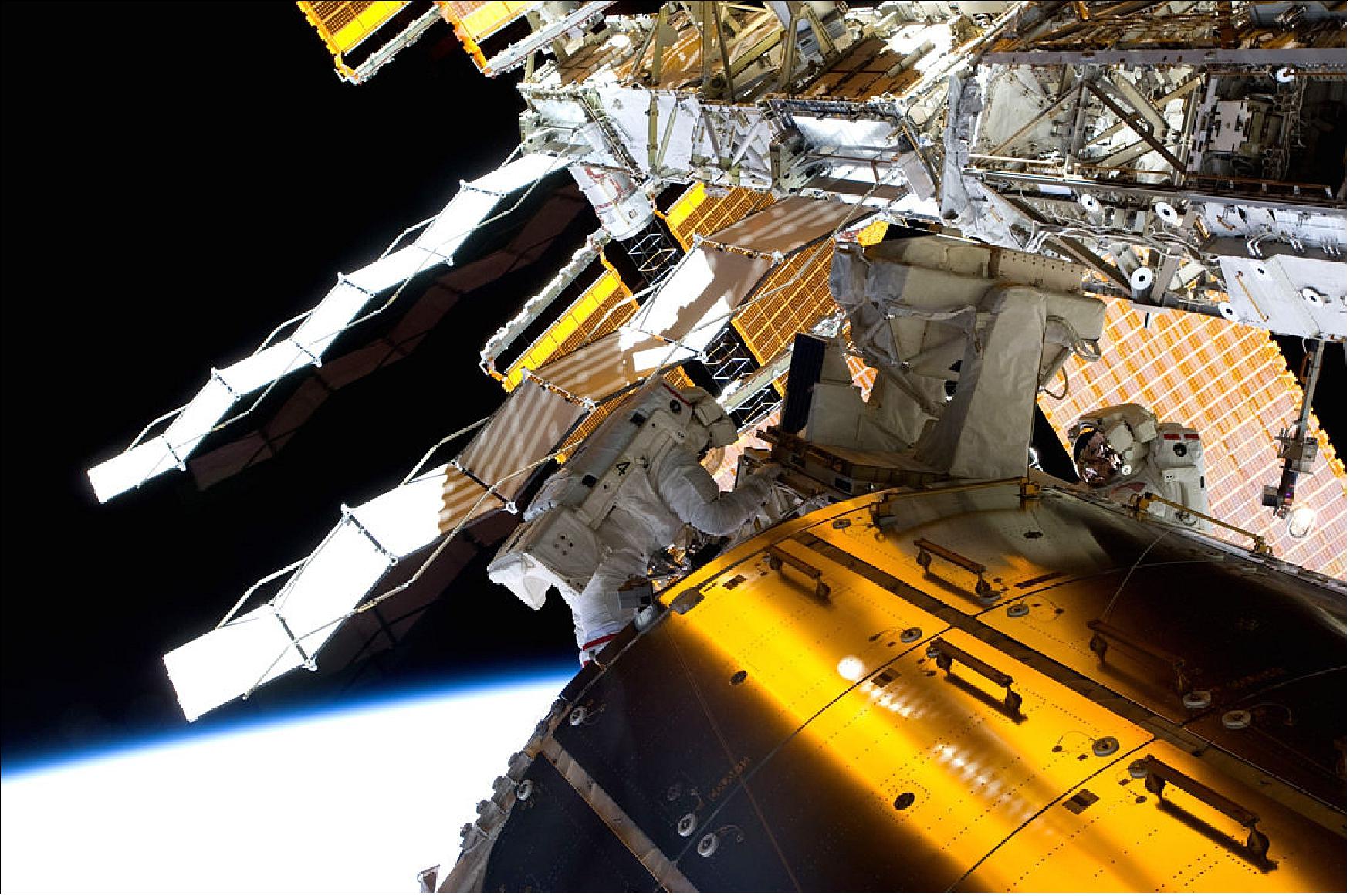

• February 05, 2018: The first permanent European research facility in space, the Columbus module – seen partially in the bottom right of this image of Figure 23 – was delivered 10 years ago this week. It has been home to a multitude of microgravity experiments covering fluid physics, materials science and life sciences, many of which are relevant to broader topics in space science. 39)

- The facility, and the subsequent suites of ‘Expose' experiments, hosted experiments requiring exposure to the space environment, such as the harsh vacuum of space, ultraviolet radiation from the Sun, and extreme freeze–thaw temperature cycles. The experiments held a variety of organisms exposed to such conditions for long periods, to test the limits of life. Bacteria, seeds, lichens and algae, as well as small organisms called tardigrades or ‘water bears', have spent months enduring these conditions and returned to Earth alive and well, proving that life that can survive spaceflight.

- Exobiology studies like this are particularly important for understanding if life could survive a journey through space between planets, or, for example, have endured the harsh conditions elsewhere in the Solar System. To that end, Expose had special compartments to recreate the martian atmosphere by filtering some sunlight and retaining some pressure, to investigate to what extent terrestrial life can cope with the extreme conditions on the Red Planet.

- Exobiology is also at the heart of the ExoMars program, which will launch a rover to Mars in 2020 to probe beneath the surface, to search for any signs that life may have existed on our neighbor planet.

- The Solar Monitoring Observatory SOLAR, which studied the Sun with unprecedented accuracy across most of its spectral range, was also installed externally on Columbus. The instrument has contributed to solar and stellar physics and increased our knowledge of how the Sun interacts with Earth's atmosphere, an important aspect in understanding what makes a planet habitable.

- In the future, the Atmosphere–Space Interactions Monitor, ASIM, will be installed outside Columbus to monitor electric events at high altitudes. These include red sprites, blue jets and elves that are thought to be triggered by electrical discharges in the upper atmosphere. These powerful electrical charges can reach high above the stratosphere and have implications for how our atmosphere protects us from radiation from space.

- A fascinating new experiment that will expand the range of research on Columbus is also coming soon with the addition of the Atomic Clock Ensemble in Space, ACES. Accurate to a second in 300 million years, it will enable the most precise measurement of time and frequency in space yet, essential to probe fundamental theories proposed by Albert Einstein with a precision that is impossible in laboratories on Earth.

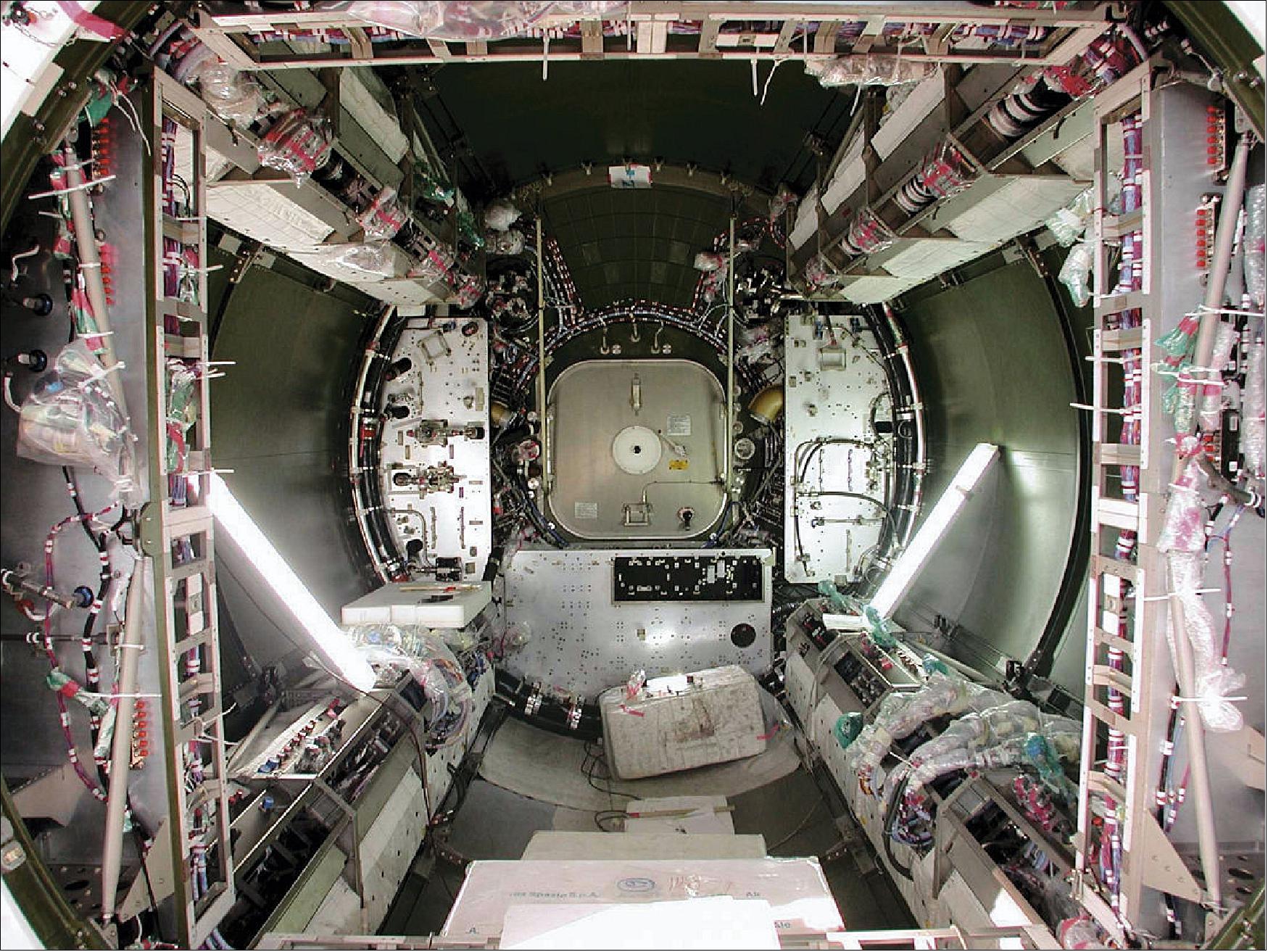

• January 30, 2018: The year: 2007. The place: Cape Canaveral. The Columbus module, built in Italy and shipped from Germany, is undergoing tests at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. 40)

- This unique interior view features some of the hardware that makes Columbus a world-class laboratory (Figure 24). Resembling airline galley storage units, the ‘racks' are highly compact facilities for research in various scientific disciplines.

- Each rack is the size of a telephone booth and can host autonomous and independent laboratories, complete with power and cooling systems. Video and data links send results back to researchers on Earth.

- From left to right are the European Drawer Rack, a flexible experiment carrier; the European Physiology Modules for experiments focusing on the human body; Biolab for life sciences experiments; and the Fluid Science Lab for studying fluids in microgravity.

- The four are seen here in their launch configuration. The racks were later relocated inside Columbus once in orbit.

- Thanks to these and other facilities in Columbus, researchers have been able to conduct multidisciplinary research in microgravity over the past decade.

- From studying immune cells to understand how they function to developing technology that finds its way to Earth, Columbus and its suite of research equipment have hosted more than 225 experiments and generated countless scientific papers.

- On 7 February, ESA is celebrating 10 years of Europe's gateway to space research at our technical heart in the Netherlands. The event is a unique opportunity to re-live some exciting milestones, connect live to the Station and look into space exploration plans.

- The larger Columbus family of planners, builders, scientists, support teams and astronauts will gather to celebrate the past, present and future of Europe's major contributions to the Station.

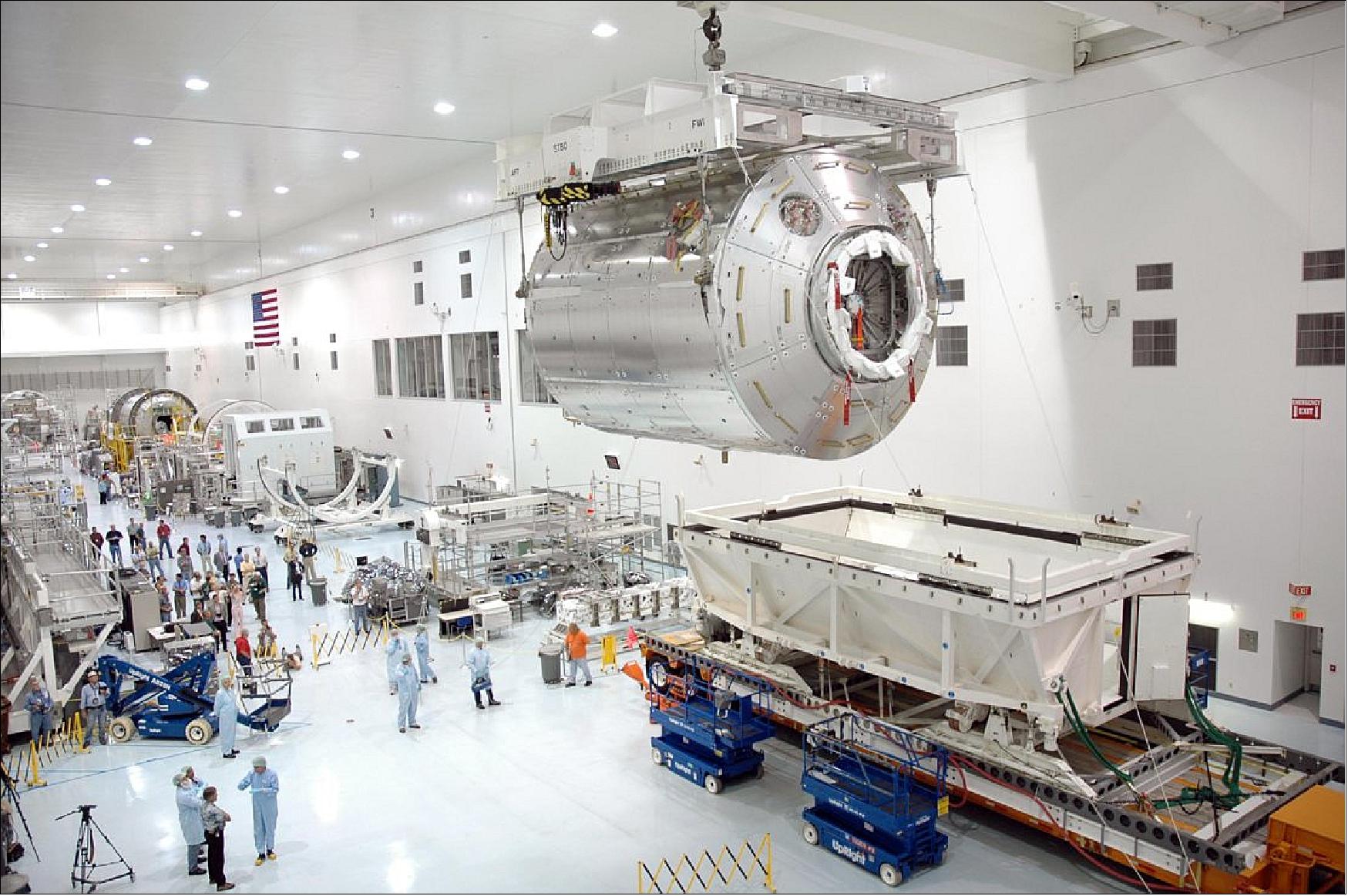

• January 23, 2018: The focus of this image is the suspended European Columbus module being moved onto a work stand in a cleanroom at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, USA. 41)

- Of course, a cylindrical module of more than 10 t (without payloads) for housing laboratory equipment, storage units and three working astronauts is big, but the contrast between Columbus and the people in the image is startling. Even more so when we remember that Columbus is one of 16 similarly sized modules orbiting 400 km over our heads.

- Countless teams across Europe were involved in the planning, building and assembly of the parts that make up this orbital lab. Teams of people were involved in shipping Columbus across the Atlantic, where it was carefully received by even more partners in the greatest human endeavor.

- It would be another year and half before Columbus made its way to the International Space Station, in 2008. Ten remarkable years later, there is much to celebrate about this long-planned and hard-earned European contribution to the international space community.

- To mark the occasion, ESA is hosting a get-together of the larger Columbus family of planners, builders, scientists, support teams and astronauts at our technical heart in the Netherlands on 7 February. The event will be livestreamed to the public, with more details coming soon.

• January 16, 2018: In 1492 Columbus sailed the ocean blue ...In 2008 another Columbus sailed into space. Next month, Europe's Columbus laboratory achieves 10 years in orbit. Circling our planet at 28,800 km/h, this element of the International Space Station created space history as the first European module dedicated to long-term research in weightlessness. 42)

- Like the transatlantic voyages that Christopher Columbus made half a millennium ago, the Columbus module was meticulously planned, budgeted, scrapped and redesigned before getting the official blessing to build, ship and launch.

- The laboratory ascended to orbit aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, USA on 7 February 2008. Nestling in the spaceplane's cargo bay, Columbus was accompanied by a seven-man crew.

- On 11 February 2008, the crew on the International Space Station captured the new arrival. At that moment, Columbus became Europe's first permanent human outpost in orbit and Europe became a full partner of the International Space Station.

- Columbus houses as many disciplines as possible in a small volume, from astrobiology to solar science through metallurgy and psychology – more than 225 experiments have been carried out during this remarkable decade. Countless papers have been published drawing conclusions from experiments performed in Columbus.

- To mark the momentous occasion, the larger Columbus family of planners, builders, scientists, support teams and astronauts will gather to celebrate the lab at ESA's technical heart in the Netherlands on 7 February. More to come on this event soon ....

• January 16, 2018: The European Columbus module is packed up and loaded for transport to the US in this image from 2006 (Figure 28). Built in Turin, Italy, and Bremen, Germany, the completed module was shipped to NASA's facilities in Cape Canaveral, Florida ahead of its February 2008 launch aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis. 43)

- Columbus has been providing microgravity research facilities for the past decade. In honor of this milestone, this week's image celebrates Columbus' triumph over setbacks. Many events factored into its delayed launch: the bureaucratic challenge of planning and budgeting, construction delays and the tragic 2003 Columbia Shuttle disaster meant Columbus was five years behind schedule by the time it climbed into the sky.

- So it was with joy and relief when Columbus inside its climate-controlled container was loaded into the Beluga aircraft, an Airbus A300 named after the whale it resembles.

- Among the many who attended its farewell ceremony was German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

- Once at Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the fully integrated module underwent final tests before being loaded into the Shuttle payload bay.

- Since its launch in February 2008, the biggest European contribution to manned spaceflight has provided a multi-disciplinary, multi-user platform for research in biology, fluidics and physics, and technology demonstrations – and continues to do so today.

• January 9, 2018: Astronauts on the International Space Station have begun running an experiment that could shine new light on how metal alloys are formed. 44)

- How humanity has mastered metallurgy is synonymous with progress, with historians labelling periods such as the Bronze Age and the Iron Age.

- Most metals used today are mixtures – alloys – of different metals, combining properties to make lighter and stronger materials. Like baking a cake, the result depends on more than just adding the right ingredients: casting is influenced by furnace temperatures and the cooling process. Some metals are even cast in hypergravity centrifuges in the quest for the perfect alloy.

- Alloys are everywhere now, from the smartphone in your pocket to aircraft. Making lighter, resistant, self-healing or even supple alloys obviously benefits industry and consumers alike.

Solving the Problem of Transparency

- It is no wonder that we would love to peer into the inner workings of metal casting to see what is happening with our own eyes. Ideally, we should observe the process without gravity adding its extra layer of complexity. The problem, of course, is that metals are not transparent.

- ESA is running X-ray experiments on suborbital rockets but these are limited to 13 minutes of weightlessness at a time and X-rays do not reveal all.

- Instead, researchers looked at a stand-in for metals and found organic materials, carefully chosen to be transparent while solidifying like a metal.

- A first batch of mixtures arrived at the Space Station on 18 December 2017: succinonitrile, D-camphor and neopentyl glycol were delivered by a Dragon spacecraft inside a glass-wall cartridge together with a miniature toaster. This Bridgman furnace is similar to a conveyor-belt oven found in factories or fast-food restaurants. The cartridges pass through the heating element at an agonizingly slow pace: they take upwards of two days to travel 1 mm, but the experiment will run on its own for several weeks.

Melting Plastic

- An astronaut set up the Transparent Alloy furnace inside ESA's self-contained glovebox for safety and inserted the first cartridge.

- A hard disk is recording the microscopic view from two video cameras, while operators at the Spanish control center in Madrid can highlight different features using an array of colored lights.

- These experiments into fundamental phenomena are allowing scientists to understand and then control processes. Who knows what amazing metals might be created? The next metal age might just be something we can't imagine right now.

• January 9, 2018: Inside the cylindrical modules of the International Space Station is the standard stuff of technology. Wires, cables and pumps form the framework of the one-of-a-kind European Columbus laboratory, seen here in its early days of assembly. 45)

- The cornerstone of Europe's contribution to the Space Station, Columbus is a pressurized laboratory that allows astronauts to work in a comfortable and safe environment.

- This year marks the 10th anniversary of Columbus in orbit. In celebration of its remarkable decade, we will revisit the technological and scientific milestones of the lab in feature images, beginning with this one taken during its construction in 2001 (Figure 32).

- Like its sister nodes Tranquility and Harmony of NASA, Columbus' assembly began in Turin, Italy. The structure, thermal control and life-support equipment, plumbing and external protection were completed by September 2001.

- Like its sister nodes Tranquility and Harmony, Columbus' assembly began in Turin, Italy. The structure, thermal control and life-support equipment, plumbing and external protection were completed by September 2001.

- Although Columbus is the Station's smallest laboratory module, it provides the same payload volume, power, data retrieval, vacuum and venting services as the other modules, an achievement made possible thanks to careful planning.

- The lab has been supporting sophisticated research in life and physical sciences, space science, Earth observation and technology demonstrations in weightlessness for the past decade.

• Solar Research 2016: Solar activity can have significant effects not only on Earth but also on the satellites in orbit around it, which are now vital for communications and navigation on Earth. Solar EUV (Extreme UV) radiation, for instance, which is absorbed into the upper atmosphere, strongly influences the propagation of electromagnetic signals such as those emitted from navigation satellites. — ESA's Solar facility (Figure 33) was installed on the Columbus External Payload Facility in February 2008. It includes two working instruments (SolACES and SOLSPEC) that allow for highly accurate measurements of the absolute values of solar irradiance in a very large wavelength bandwidth, ranging from soft X-rays (17 nm) through the UV/VIS band to the far infrared (100 µm). The Solar package is thus contributing to the understanding of solar and stellar physics, and to Earth system sciences such as atmospheric chemistry and climatology. Data from the Solar facility have already helped to validate improved models of the upper atmosphere. 46)

The originally foreseen lifespan of Solar was 18 months to 2 years, although this has now been far exceeded with a second mission extension granted until the end of 2016. The facility will provide a great deal of data during the approximately 11-year solar cycle, during which time the Sun goes through varying degrees of increased/diminished solar activity.

As of January 2016 the Solar facility had undertaken almost 100 data acquisition periods, called Sun visibility windows, since its installation. These normally last around 10–12 days due to ISS orbital parameters and restrictions. Since 2008 the facility has been able to take measurements during some very interesting periods of solar activity:

- during a large solar storm in January 2012

- during a solar eclipse in March 2015, providing data that were useful for instrument calibration purposes

- close to the transit of Venus across the Sun in June 2012, taking simultaneous measurements with ESA's Venus Express, enabling in-orbit calibration of a Venus Express UV spectrometer

- during four extended science acquisition periods (involving rotating the ISS slightly) in order to take measurements during a whole Sun rotation cycle, which lasts around 26 days at the solar equator and up to 36 days at the solar poles. This produced excellent scientific results.

Looking at the results from the Solar facility (Nikutowski et al., 2011) 47), the length of the period of the solar EUV minimum between solar cycles 23 and 24 continued over an unexpectedly long period (roughly two years instead of one), with the facility's SolACES (Solar AutoCalibrating Extreme UV Spectrometer) instrument showing a distinct minimum in August/November 2009. At the beginning of solar cycle 24 measurements were showing abnormally low characteristics of the EUV spectral irradiance. The maximum of the current solar cycle was also previously predicted to be in late 2013. However, from SolACES measurements it was thought that the maximum may have occurred in late 2011, as solar activity declined and stagnated for a long period, before undergoing a strong increase again, culminating in a second peak of activity in early 2014.

The Solar facility will continue to serve the purpose of updating the measurements of the spectrum of solar radiation, which will provide important contributions for scientists to elaborate new and improved means to understand and deal with many aspects of Earth's climate, the atmosphere, satellite telecommunications, human health, etc., that are influenced by solar radiation. By providing details of the variability of solar EUV radiation, Solar will contribute to improving the accuracy of navigation data, as well as forecasts of the orbits of satellites and space debris.

Continued monitoring of the current solar cycle 24 is of significant scientific interest, especially in view of the abnormal behavior already measured. It would also be the first time a full set of solar spectral irradiance data would be provided and would answer open questions with respect to different solar cycle periods especially in the highly variable EUV spectral range (Ref. 46).

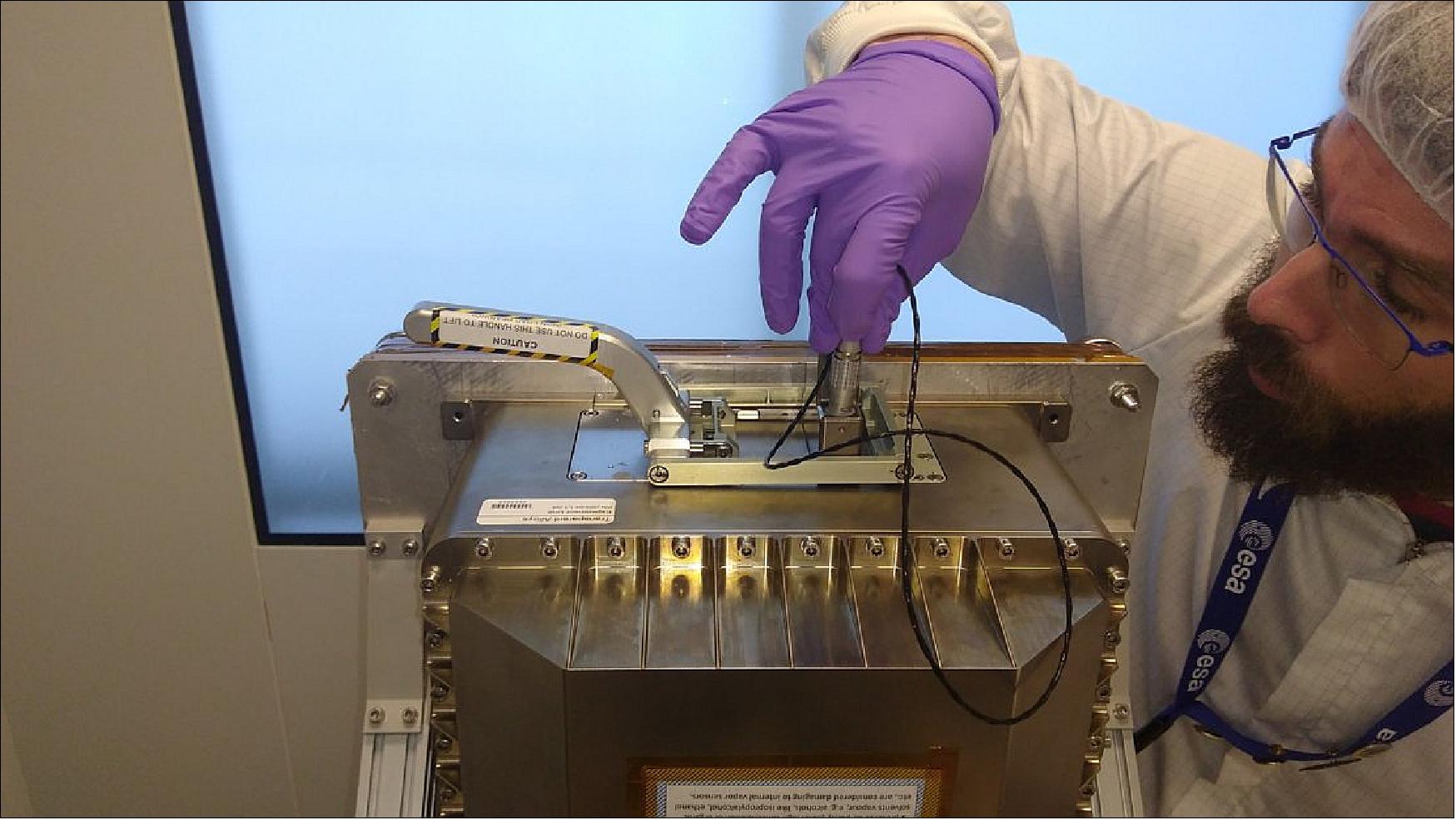

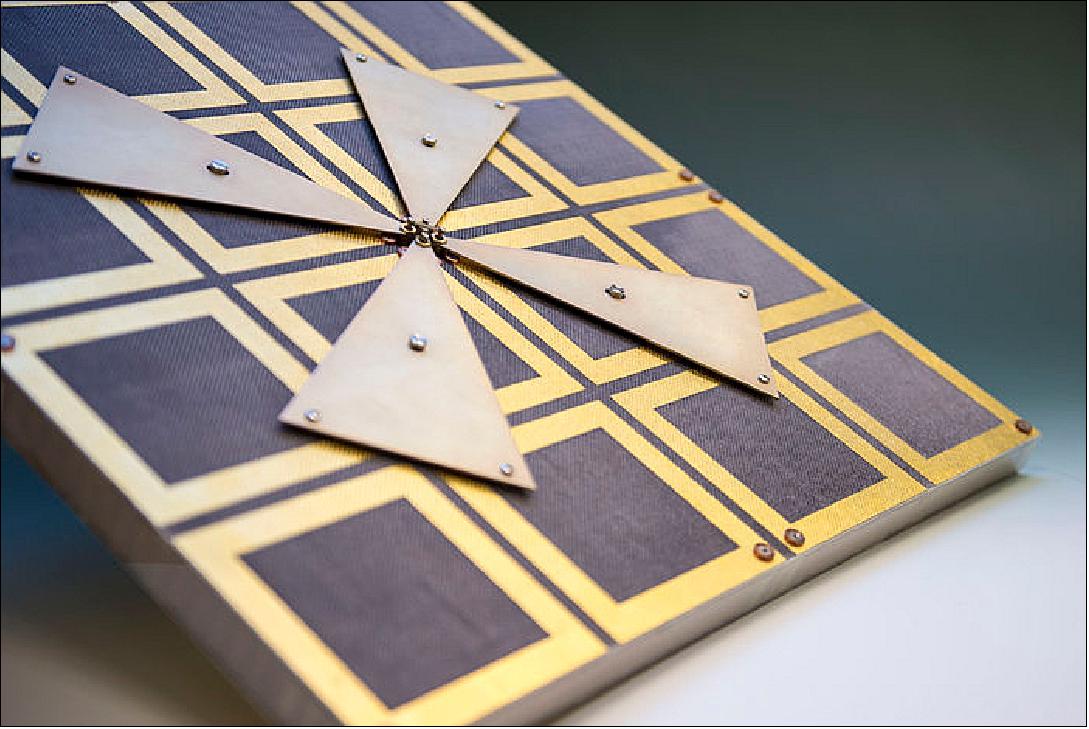

• In January 2016, ESA is reporting the development of a new prototype compact AIS antenna. "Based on our testing, this new prototype designs offers a four-fold increase in ship detection performance," explains ESA antenna specialist Nelson Fonseca, overseeing the project. 48)

- The AIS detection system (NorAIS) on Columbus employs a low-gain ‘whip' antenna, receiving signals within a very broad beam, with corresponding potential for signal overlap and interference.

- This antenna design combines higher-gain with a more reduced footprint, allowing more of a focus on regions of highest interest, and can also discriminate between polarizations, increasing the likelihood of detection for any individual AIS signal within the antenna field of view. In addition, clever engineering has shrunk the overall antenna size to a size where up to five could be hosted on a minisatellite of 1 m3 in volume.

- "Despite its name, VHF (Very High Frequency)is quite a low wavelength in space terms, implying a bulky antenna of about 1 m across and 0.5 m thick to operate ideally at that frequency," Nelson adds. "But the patterned square-shaped structure on the underlying face of our antenna changes the signal behavior, enabling us to shrink the design to 50 cm width and 3 cm thickness – making it suitable for hosting on a smaller platform."

- The antenna was developed through ESA's ARTES (Advanced Research in Telecommunications Systems) advanced technology program with Italian companies CGS SpA (Compagnia Generale per lo Spazio), Milan, Italy, as prime contractor and MVG (Microwave Vision Group) as subcontractor in charge of the electrical design.

• December 2015: The Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI) operated the NorAIS Receiver on-board the Columbus module of the ISS from June 2010 to February 2015. In addition to receiving AIS messages and demonstrating space-based AIS as a security, safety and surveillance capability for European authorities, the NORAIS Receiver was designed to collect auxiliary data about the AIS signals and signal environment in space. The intention was to collect information that would contribute to the development of more advanced decoding algorithms, and investigate in-situ the challenges that space-based AIS receivers face. 49)

• May 28, 2014: The NorAIS (Norwegian Automatic Identification System) receiver on the Columbus module of ESA is still working well in its 5th year of operations. The SDR (Software Defined Radio) has been upgraded 4 times resulting in substantial improvements to its performance in challenging areas with thousands of ships within the FOV (Field of View), i.e. the Mediterranean, the South China Sea, Gulf of Mexico and the North Sea and Baltic Sea. 50)

- Besides being used for development purposes, NorAIS has been used for demonstrations and pilot projects for ESA and the EU, as well as in support of counter-piracy operations in the Indian Ocean.

- NORAIS operations are expected to continue at least until the end of 2015, most probably even longer. The LuxAIS receiver has not been re-sent to orbit, so NorAIS is operated on a continuous basis.

- The NorAIS data from the ISS is received by the Col-CC (Columbus Control Center), located at DLR in Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany and then routed to the N-USOC in Trondheim, Norway.

• May 2014: Astronauts on the ISS can now talk with people on Earth with video using simple transmitters. ‘Ham TV' has been set up in ESA's Columbus laboratory and already used for talking with ground control. The new Ham TV adds a visual dimension, allowing an audience on the ground to see and hear the astronauts. 51) 52)

- The hardware, developed by Kayser Italia, was sent to the space station on Japan's space freighter in August 2013 and connected to an existing S-band antenna on Columbus.

- NASA astronaut Mike Hopkins had the honor of being the first to commission the unit and broadcast over Ham TV. He had a video chat with three ground stations in Italy: Livorno, Casale Monferrato and Matera. The crew finished commissioning the set-up on April 12, 2014 for general use. Just like standard television, the video signal is one way. The astronauts cannot see their audience but they will still be able to hear them over the traditional amateur radio on the space station.

- ESA has provided five ground antennas and equipment to the Amateur Radio on the International Space Station organization to receive video from the station. These stations can be transported easily and positioned to follow the laboratory as it flies overhead. Linked together in this way, the stations can supply up to 20 minutes of contact at a time.

![Figure 35: Photo of the Ham TV equipment [image credit: AMSAT, ARISS (Amateur Radio on the ISS)] 53)](https://eoportal.org/ftp/satellite-missions/iss/Columbus_180122/Columbus_Auto1.jpeg)

• May 2, 2014: Solar facility on Columbus (SOLSPEC and SolACES): The SOLAR payload facility has been studying the Sun's irradiation with unprecedented accuracy across most of its spectral range since 2008. This has so far produced excellent scientific data during a series of Sun observation cycles. An extension to the payload's time in orbit could see its research activities extend up to early 2017 to monitor the whole solar cycle with unprecedented accuracy. 54)

• Feb. 12, 2013: The European Columbus laboratory module was attached to the International Space Station five years ago, it has offered researchers worldwide the opportunity to conduct science beyond the effects of gravity. 55)

- A total of 110 ESA-led experiments involving some 500 scientists have been conducted since 2008, spanning fluid physics, material sciences, radiation physics, the Sun, the human body, biology and astrobiology.

- Col-CC (Columbus Control Center), located at the DLR (German Aerospace Center) facility in Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany, works closely with the other ISS control centers including Houston and Moscow. Col-CC is responsible for all Columbus systems and for European science activities on board the ISS. 56)

• Fall 2011: With the establishment of Columbus in orbit, the approaching launch of ATV-3 and a fully established six-member ISS crew in orbit, Europe is now fully immersed in routine scientific operations and utilization of the International Space Station. Following the years of preparation the investments made are now starting to bear more fruit. Columbus is outfitted with a full quota of research facilities and the availability of the Material Science Laboratory and other payloads in ISS partner laboratories has expanded research possibilities on the ISS further. 57) 58)

- After 3 ½ years of Columbus operations the number of experiments, and in particular their scope, duration and complexity, has significantly increased. During its initial period of operation, the Columbus Laboratory proved to be a very robust element of in-orbit infrastructure and is now proving itself as a workhorse of European research in LEO (Low Earth Orbit).

- Preparations for future experiments are ongoing and several new payloads or experimental inserts for the existing Columbus research facilities are nearing their completion and launch. In addition, utilization strategies and future scientific and technological priorities have been identified and are addressed in various ongoing studies that will lead to new instrumentation and payloads in order to satisfy the high European research demand.

- Very fruitful research collaborations with other ISS Partners have already been successfully implemented and further promising perspectives identified in order to maximize the ISS yield by optimum use and share of all available on-orbit assets and crew resources. An exciting era for ESA and the European scientific and industrial user community is continuing, and bodes well for promising scientific future and challenging new objectives in space exploration.

• In the fall of 2010, 2 ½ years after operations started in the Columbus module, the FCT (Flight Control Team) is busy to prepare and execute operations in the European module, taking into account the larger workforce onboard ISS, since the permanent 6 person crew has been established in May 2009. 59)

In the last 12 months a continuous flow of known and new maintenance activities have been performed to ensure that all capabilities of the module are permanently available and full support for payload operations can be given.

• On 1 June 2010, the COLAIS (Columbus Automatic Identification System) experiment with the NorAIS receiver was switched on. More than 90,000 Class A AIS messages were gathered by between 1900 GMT on 2 June and 0900 GMT on 3 June. 60)

• Operations coordination with JAXA for Matroshka: A very new chapter in ISS operation was the introduction of a closer interface between Col-CC and the Space Station Integration and Promotion Center (SSIPC) in Tsukuba (Japan). This new interface was introduced by moving Matroshka to the Kibo module. Matroshka is a torso equipped with dosimeter to measure the radiation inside a structure comparable to a human body. The experiment will reside inside JEM for several months until the dosimeter will be brought back to Earth for analysis in 2011.

• During 2009, the DMS (Data Management System) failures represented one of the most challenging events in Columbus module operations.

- Already in the beginning of 2009 a first DMS failure had occurred which could be solved by a partial shutdown and reactivation of the Columbus onboard computer system.

- Throughout the year 2009 and also before and after the Cycle 12 transition the DMS worked without problems.

- Nevertheless on 18 February 2010 a failure occur-red in the nominal DMS leading to partial loss of Columbus onboard functions while the Space Shuttle was docked to the Station.

• Since the summer of 2008 Col-CC supports B-USOC (Brussels-User Operation and Support Center) by taking over the monitoring of the SOLAR external payload if it is in the so-called "idle" mode. This releases B-USOC from a 24/7 shift scheme during that phase that the small team at B-USOC can concentrate on the monitoring and commanding of the external payload in the active phases.

• The Columbus module was permanently attached to the ISS in February 2008 — and is expected to be utilized at least up to 2020, with a final confirmation expected from the International Partners by the end of 2010 in the context of deciding upon the overall continuation of the ISS.

References

1) Jason Hatton, "The ISS as an Earth observation platform - Attitude stability, data rates, constraints and example international partner Earth observation payloads," URL: http://esamultimedia.esa.int/docs/hsf_research/Climate

_change_ISS_presentations/ISS-as-observation-platform-Hatton.pdf

2) A. Thirkettle, B. Patti, P. Mitschdoerfer, R. Kledzik, E. Gargioli, D. Brondolo, "ISS: Columbus," ESA Bulletin, No 109, February 2002, pp. 27-34, URL: http://www.esa.int/esapub/bulletin/bullet109/chapter4_bul109.pdf

3) "Columbus - A new European science laboratory in Earth orbit," URL: http://esamultimedia.esa.int/docs/columbus/newspaper/ESA_ColumbusLab_newspaper_ENG.pdf

4) Martin Zell, Jennifer Ngo-Anh, Jason Hatton, Olivier Minster, David Jarvis, Eric Istasse, Jon Weems, "ESA Science and Applications Program on ISS," Proceedings of the 64th International Astronautical Congress (IAC 2013), Beijing, China, Sept. 23-27, 2013, paper: IAC-13-B3.3.3.2

5) http://www.esa.int/SPECIALS/Columbus/ESAFRG0VMOC_0.html

6) http://www.esa.int/esaCP/SEMTTQ73R8F_index_1.html#subhead2

7) "Europe on board the space station," Research, No 57, July 2008, URL: http://ec.europa.eu/research/research-eu/57/article_5730_en.html

8) NASA-ESA Agreement, Sept. 29, 1988, URL: http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/structure/elements/nasa_esa.html

9) "Columbus Laboratory Agreements," URL: http://esamultimedia.esa.int/docs/columbus

/infokit/english/13_AgreementsAndIndustry_new.pdf

10) "Columbus Development History," URL: http://esamultimedia.esa.int/docs/columbus

/infokit/english/15_ColumbusDevelopmentHistory_new.pdf

11) R. Veldhuyzen, E. Grifoni, "No Exchange of Funds – The ESA Barter Agreements for the International Space Station," ESA Bulletin, No 99, Sept. 1999, URL: http://www.esa.int/esapub/bulletin/bullet99/veld99.pdf

12) R. Barbera, "Overview of the Columbus programme," Acta Astronautica, Volume 35, Issues 9-11, May-June 1995, pp.725-732

13) "Agreement Between the United States of America and other Governments," January 29, 1998, URL: http://www.spacelaw.olemiss.edu/library/space/International_Agreements/Mulilateral

/ISS_IGA/1998%20-%20Agreement%20Among%20Canada,%20ESA

%20States,%20Japan,%20Russia,%20and%20the%20United.pdf

14) A. Petrivelli, "The ESA Laboratory Support Equipment for the ISS," ESA Bulletin, No 109, February 2002, URL: http://www.esa.int/esapub/bulletin/bullet109/chapter5_bul109.pdf

15) Alan Thirkettle, Bernardo Patti, "Columbus Begins its Voyage of Discovery," ESA Bulletrin, No 127, August 2006, URL: http://www.esa.int/esapub/bulletin/bulletin127/bul127e_thirkettle.pdf

16) "European Experiment Programme," Columbus Mission Information Kit, ESA, January 2008, URL: http://esamultimedia.esa.int/docs/columbus/infokit

/english/11_EuropeanExperimentProgramme_new.pdf

17) Julian Doyé, Andreas O. Kohlhase, Norbert Porth, "An Advanced Columbus Thermal and Environmental Control System," Proceedings of SpaceOps 2012, The 12th International Conference on Space Operations, Stockholm, Sweden, June 11-15, 2012

18) Giuseppe Reibaldi, Rosario Nasca, Horst Mundorf, Pierfilippo Manieri, Giacinto Gianfiglio, Stephen Feltham, Piero Galeone, Jan Dettmann, "The ESA Payloads for Columbus," ESA Bulletin, No 122, May 2005, pp. 59-70, URL: http://www.esa.int/esapub/bulletin/bulletin122/bul122h_reibaldi.pdf

19) Rosario Nasca, "The Columbus External Payload Facility (CEPF) and the ESA observation Payloads (SOLAR and ASIM)," ESA, Dec. 7, 2009, URL: http://esamultimedia.esa.int/docs

/hsf_research/Climate_change_ISS_presentations/CEPF_Nasca.pdf

20) "Columbus to host worldwide sea traffic tracking experiment," ESA, Sept. 18, 2009, URL: http://www.esa.int/SPECIALS/Space_Engineering/SEMWN5W0EZF_0.html

21) "Tracking Ships From ISS," NordicSpace, URL: http://www.nordicspace.net/PDF/NSA240.pdf

22) C. Pütz, M. P. Heß, B. Hummelsberger, K. Hausner, R. Nasca, L. Cacciapuoti, R. Much, D. Massonnet, P. Rochat, D. Goujon, W. Schäfer, I. Prochazka, "ACES (Atomic Clock Ensemble in Space) Mission Status and Outlook," Proceedings of IAC 2011 (62nd International Astronautical Congress), Cape Town, South Africa, Oct. 3-7, 2011, IAC-11.A2.1.4

23) "Atomic Clock Ensemble in Space (ACES)," Oct. 25, 2011, URL: http://www.esa.int/SPECIALS/HSF_Research/SEMJSK0YDUF_0.html

24) "Columbus operations," ESA, April 12, 2011, URL: http://www.esa.int/esaMI/Operations/SEMW3L161YF_0.html

25) "Columbus Control Centre, Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany," URL: http://www.esa.int/esaMI/Columbus/SEMHZ373R8F_0.html

26) Austin L. Gosling, Jürgen Hummel, Osvaldo Peinado, "Columbus Payload Data Handling," Proceedings of SpaceOps 2008 Conference, Heidelberg, Germany, May 16-18, 2008, AIAA 2008-3400

27) Florian Marks, Osvaldo Peinado, "Adaption of the Col-CC Integrated Management System to the new MPLS network," Proceedings of the SpaceOps 2010 Conference, Huntsville, ALA, USA, April 25-30, 2010, AIAA 2010-2177

28) Stefan Maly, "From ATM/ISDN to MPLS – Transition of the Columbus Interconnection Ground Segment network," Proceedings of the SpaceOps 2010 Conference, Huntsville, ALA, USA, April 25-30, 2010, AIAA 2010-1977

29) Thomas Mueller, "Col-CC Voice System Migration During On-Going Operations," Proceedings of SpaceOps 2012, The 12th International Conference on Space Operations, Stockholm, Sweden, June 11-15, 2012

30) Alberto Novelli, "The operations of the ESA ISS elements during the year 2010," Proceedings of the 61st IAC (International Astronautical Congress), Prague, Czech Republic, Sept. 27-Oct. 1, 2010, IAC-10.B6.1.8

31) "Space Station communications infographic of the Columbus module," ESA Science & Exploration, 17 January 2022, URL: https://www.esa.int/ESA_Multimedia/Images/2021/01/Space_Station_communications_infographic

32) "The International Space Station connected via the SpaceDataHighway," Airbus Press Release, 17 January 2022, URL: https://securecommunications.airbus.com/en/news/the-international-space-station-connected-via-the-spacedatahighway

33) "Call for innovation to advance Europe's lab in space," ESA, Human and Robotic Exploration, 10 October 2019, URL: http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Human_and_Robotic_Exploration/Call

_for_innovation_to_advance_Europe_s_lab_in_space

34) "Space behavior," ESA, 19 February 2019, URL: http://m.esa.int/Our_Activities/Human_and_Robotic_Exploration/International

_Space_Station/Space_behaviour

35) "Horizons science: perceiving time in space," ESA, 19 July 2018, URL: http://m.esa.int/spaceinvideos/Videos/2018/07/Horizons_science_perceiving_time_in_space

36) "Hundreds of impacts crater ESA's Columbus science laboratory," ESA, 23 January 2019, URL: http://m.esa.int/Our_Activities/Operations/Hundreds

_of_impacts_crater_ESA_s_Columbus_science_laboratory

37) "Columbus and ATV 10th anniversary," ESA, 07 Feb. 2018, URL: http://m.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images/2018/02/Columbus_and_ATV_10th_anniversary9

38) "T-1," ESA, 6 Feb. 2018, URL: http://m.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images/2018/02/T_1

39) "Space station space science," ESA Space Science Image of the Week, 05 Feb. 2018, URL: http://m.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images/2018/02/Space_station_space_science

40) "2007: A space odyssey," ESA, Human Spaceflight and Exploration image of the week, Released 30 Jan. 2018, URL: http://m.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images/2018/01/2007_A_space_odyssey

41) "Columbus to scale," ESA Human Spaceflight and Exploration image of the week, 23 Jan. 2018, URL: http://m.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images/2018/01/Columbus_to_scale

42) "Columbus: 10 years a lab," ESA, 16 Jan. 2018, URL: http://m.esa.int/Our_Activities/Human_Spaceflight/Columbus/Columbus_10_years_a_lab

43) "Setting sail," ESA, Human Spaceflight and Exploration image of the week, 16 Jan. 2018, URL: http://m.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images/2018/01/Setting_sail

44) "See-through metals," ESA, 9. Jan. 2018, URL: http://m.esa.int/Our_Activities/Human_Spaceflight/Research/See-through_metals

45) "Columbus stripped," ESA, 9. Jan. 2018, URL: http://m.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images/2018/01/Columbus_stripped

46) Michael Rast, "ESA's Report to the 41st COSPAR Meeting,"(ESA SP-1333, June 2016), Istanbul, Turkey, July-August 2016, "Solar Research," pp: 46-50, URL: http://esamultimedia.esa.int/multimedia/publications/SP-1333/SP-1333.pdf

47) B. Nikutowski, R. Brunner, Ch. Erharda, St. Knecha, G. Schmidtke, "Distinct EUV minimum of the solar irradiance (16–40 nm) observed by SolACES spectrometers onboard the International Space Station (ISS) in August/September 2009," Advances in Space Research, Volume 48, Issue 5, 1 September 2011, pp: 899–903

48) "Compact AIS antenna," ESA, Jan. 15, 2016, URL: http://www.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images/2016/01/Compact_AIS_antenna

49) Andreas Nordmo Skauen,, Øystein Olsen, "Signal environment mapping of the Automatic Identification System frequencies from space, "Advances in Space Research, Volume 57, Issue 3, 1 February 2016, pp: 725–741; Science Direct, Available online 14 December 2015, URL: http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0273117715008364/1-s2.0-S0273117715008364-main.pdf?_tid

=eb65c6b2-bf7a-11e5-b2bc-00000aab0f01&acdnat=1453297216_ce17d5dfbcad03a096e1ffb6fdb85e45

50) Information provided by Richard B. Olsen of FFI (Norwegian Defence Research Establishment), Kjeller, Norway

51) Ham video premiers on Space Station," ESA, May 5, 2014, URL: http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities

/Human_Spaceflight/Education/Ham_video_premiers_on_Space_Station

52) "HAM Video Premieres on the Space Station," NASA, May 15, 2014, URL: http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/research/news/ham_tv/

53) "Ham Video," ARISS Europe, URL: http://www.ariss-eu.org/

54) "ESA ISS Science & System - Operations Status Report # 167 Increment 39: 12-25 April 2014," ESA, May 2, 2014, URL: http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Human_Spaceflight/Columbus/ESA

_ISS_Science_System_-_Operations_Status_Report_167_Increment_39_12_25_April_2014

55) "Five years of unique science on Columbus," ESA, Feb. 12, 2013, URL: http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Human_Spaceflight/Columbus

/Five_years_of_unique_science_on_Columbus

56) "Columbus research laboratory in microgravity for five years," DLR, Feb. 8, 2013, URL: http://www.dlr.de/dlr/en/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-10261/371_read-6261

57) Martin Zell, Christer Fuglesang, Oliver Minster, Patrik Sundblad, Eeric Istasse, Josef Winter, Lina de Parolis, "Achievements and outlock of the ISS utilization program of the European Space Agency," Proceedings of IAC 2011 (62nd International Astronautical Congress), Cape Town, South Africa, Oct. 3-7, 2011, paper: IAC-11-B3.3.3

58) "ESA ISS Science & System - Operations Status Report # 105 Increment 29," ESA, Oct. 21, 2011, URL: http://www.esa.int/esaMI/Columbus/SEMLVQCUHTG_0.html

59) Dieter Sabath, Dirk Schulze-Varnholt, Alexander Nitsch, "Highlights in Columbus Operations and Preparation for Assembly Complete Operations Phase," Proceedings of the 61st IAC (International Astronautical Congress), Prague, Czech Republic, Sept. 27-Oct. 1, 2010, IAC-10.B6.1.5

60) Giuseppe Reibaldi, "Utilization of the Columbus Laboratory by the European Union," Proceedings of the 61st IAC (International Astronautical Congress), Prague, Czech Republic, Sept. 27-Oct. 1, 2010, IAC-10.B6.6.-B3.4.5

61) Garcia, Mark. “Partners Extend International Space Station for Benefit of Humanity – Space Station.” NASA Blogs, 27 April 2023, https://blogs.nasa.gov/spacestation/2023/04/27/partners-extend-international-space-station-for-benefit-of-humanity/

The information compiled and edited in this article was provided by Herbert J. Kramer from his documentation of: "Observation of the Earth and Its Environment: Survey of Missions and Sensors" (Springer Verlag) as well as many other sources after the publication of the 4th edition in 2002. - Comments and corrections to this article are always welcome for further updates (eoportal@symbios.space).

Launch Experiments Payloads Module Status References Back to Top