Biomass (Earth Explorer 7)

EO

ESA

Land

Vegetation

The Biomass satellite mission focuses on biomass monitoring for carbon assessment. Launched in April 2025 and led by the European Space Agency (ESA) as the seventh Earth Explorer, Biomass will address the status and dynamics of forests for a better understanding of the carbon cycle.

Quick facts

Overview

| Mission type | EO |

| Agency | ESA |

| Mission status | Commissioning |

| Launch date | 29 Apr 2025 |

| Measurement domain | Land |

| Measurement category | Vegetation |

| Measurement detailed | Above Ground Biomass (AGB), Vegetation Canopy (height), Vegetation Canopy (cover) |

| Instruments | P-Band SAR |

| Instrument type | Imaging microwave radars |

| CEOS EO Handbook | See Biomass (Earth Explorer 7) summary |

Related Resources

Summary

Mission Capabilities

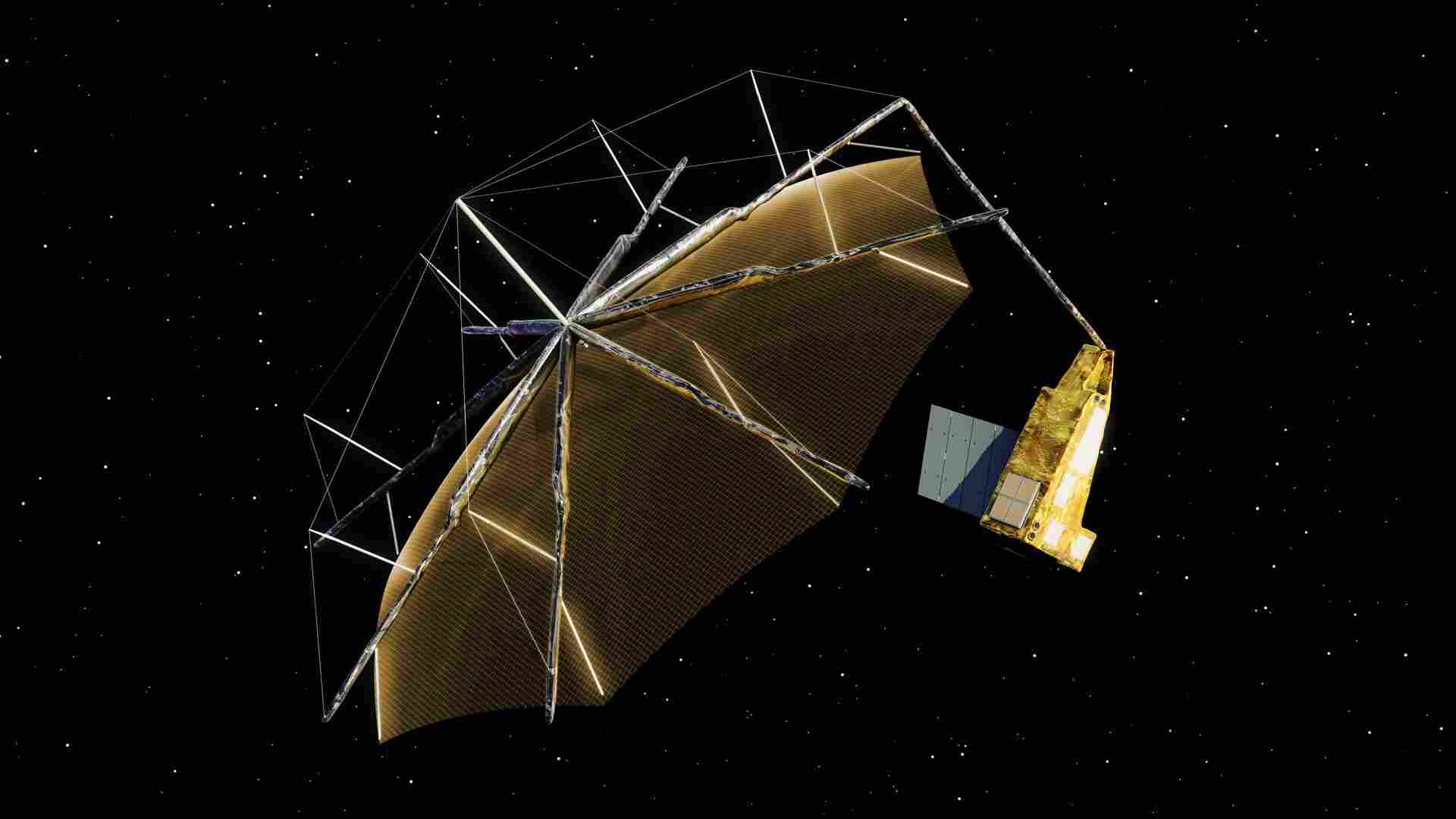

Biomass carries a P-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (P-SAR) onboard, which has a single-offset reflector antenna system consisting of a feed array and a large deployable mesh reflector with a circular projected aperture diameter of 12 m. The P-band wavelength enables observations of above ground biomass and forest height. Secondary observations will include the topography under by dense vegetation, subsurface geomorphologic features in deserts and the structure of ice sheets. This data can additionally be used to provide scientific support for international treaties and agreements, improve predictions of landscape-scale carbon dynamics, provide observations to initialise and test the land element of Earth system models, reduce uncertainties in carbon flux and provide key information for forest resources management.

Performance Specifications

P-SAR will operate in a Stripmap mode with a swath width of approximately 50 km illuminated by a single antenna beam. Global coverage will be obtained by the interleaved stripmap operations among three complementary swaths, with the operating incidence range between 23° and 35°. P-SAR will provide accurate, frequent and global information on forest properties at a spatial scale of 200 m, making it possible to address a range of critical issues.

Biomass will be placed in a sun-synchronous near circular dawn-dusk orbit at an altitude of approximately 666 km and an inclination of 97.97°. The baseline observation principle is based on a drifting orbit with a 3 days repeat cycle to enable interferometric data processing. The mission will be operated in two mission phases. During the first 18 months the mission will be operated in a tomographic observation mode building stacks of 7 images of each point on the earth. The following 3.5 years the mission will be operated in an Interferometeric mode with building stacks of 3 images of each point on the earth.

Space & Hardware Components

The Biomass spacecraft comprises a single satellite platform carrying the P-SAR, with the design largely constrained by the accommodation of the SAR antenna on a 12 m deployable reflector. This large antenna with an offset feed array and a single beam enables a high level of map accuracy and must be folded for launch inside a Vega launcher.

Airbus Defence and Space UK have been contracted to develop the spacecraft with Harris Corporation to provide the 12 m deployable reflector and precision boom assembly. The mission was successfully launched on 29 April 2025.

Biomass (Earth Explorer 7)

Overview

The Biomass mission will address a fundamental gap in our understanding of the land component of the Earth system, which is the status and the dynamics of Earth’s forests, as represented by the distribution of forest biomass and its changes. With accurate, frequent and global information on these forest properties at a spatial scale of 200 m, it will be possible to address a range of critical issues with far-reaching scientific and societal consequences.

In particular, the Biomass mission will help to:

- reduce the large uncertainties in the carbon flux due to changes in land use

- provide scientific support for international treaties, agreements and programs such as the UN’s REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries) program

- improve understanding and predictions of landscape-scale carbon dynamics

- provide observations to initialise and test the land element of Earth system models

- provide key information for forest resources management and ecosystem services.

The Biomass mission will explore Earth’s surface for the first time at the P-band wavelength. The observations can have a wide range of as yet unforeseen applications (mapping subsurface geological features in deserts in support of palaeohydrological studies and ice sheets, the surface topography of areas covered by dense vegetation).

Biomass addresses one of the most fundamental questions in our understanding of the land component in the Earth system, namely the status and the dynamics of forests, as represented by the distribution of biomass and how it is changing.

Gaining accurate and frequent information on forest properties at scales that allow changes to be observed will mean that the scientific community is equipped to address a range of critical issues with far-reaching benefits for science and society. Moreover, Biomass will greatly improve our knowledge of the size and distribution of the terrestrial carbon pool. And provide much-improved estimates of terrestrial carbon fluxes. In addition, the mission responds to the pressing need for biomass observations in support of global treaties such as the UN REDD+(Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) initiative – an international effort to reduce carbon emissions from deforestation and land degradation in developing countries. 9) 10) 11) 12) 13) 14) 15)

In addition, the measurements made by Biomass offer the opportunity to map the elevation of Earth’s terrain under dense vegetation, yielding information on subsurface geology and allowing the estimation of the glacier and ice-sheet velocities, critical to our understanding of ice-sheet mass loss in a warming Earth.

Biomass also has the potential to evolve into an operational system, providing long-term monitoring of forests – one of Earth’s most important natural resources.

Biomass Selected as Earth Explorer 7

In response to ESA's Second Call for Earth Explorer Opportunity Missions in March 2005, a P-band SAR payload was proposed to provide the spatial distribution and dynamics of forest biomass. 17)

In 2009, the three candidate Earth Explorer Core missions, namely Biomass, CoReH2O (Cold Regions Hydrology high-resolution Observatory) and PREMIER (Process Exploration through Measurement of infrared and millimeter-wave Emitted Radiation) were selected for feasibility study and their resulting Reports for Mission Selection were published in June 2012. 19) 20)

On March 2, 2013, Biomass was among the three missions down selected for phase A studies. Following the User Consultation Meeting held in Graz, Austria on 5-6 March 2013, the Earth Science Advisory Committee (ESAC) has recommended implementing Biomass as the 7th Earth Explorer Mission within the frame of the ESA Earth Observation Envelope Program. On May 7, 2013, ESA's Earth Observation Program Board selected Biomass to become the seventh Earth Explorer mission. 1)

On Feburary 18, 2015, the ESA Member States gave the green light for the Biomass mission full implementation. 21)

On April 29, 2016, ESA and Airbus Defence and Space UK signed a €229 million contract to build the next Earth Explorer: Biomass. 22)

The primary scientific objectives of the Biomass mission are to determine the distribution of above-ground biomass in the world forests and to measure annual changes in this stock throughout the mission to greatly enhance our understanding of the land carbon cycle. To achieve these objectives, the Biomass sensor will consist of a P-band (435 MHz) Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) in side-looking geometry with full polarimetric and interferometric capabilities. The main architectural elements of the Biomass mission are shown in Figure 2. 23) 24) 25) 26) 27) 28) 29)

Biomass will provide global maps of forest biomass stocks at a spatial resolution in the order of 4 ha, once a year over the life of the five-year mission. These maps will greatly improve existing forest inventories and give vastly improved information for managing Earth’s forest resources.

Biomass will also provide maps of biomass change, which can be linked to disturbance, degradation, land-use change, and forest growth. In addition, the full resolution of the instrument of around 0.25 ha will be used to detect deforestation; linking this to the coarser resolution maps of biomass will allow associated carbon losses to be estimated at scales commensurate with the processes of land-use change. The Biomass observation requirements have been derived from these high-level objectives (Table 2).

Parameter | Requirement |

Instrument type | P-band full polarimetric interferometric SAR |

Center frequency | 435 MHz (P-band, 70 cm wavelength) |

Bandwidth | 6 MHz (ITU allocation) |

Near incidence angle | >23º (threshold); 25º (goal) |

Cross-polarisation ratio (cross-talk) | ≤-25 dB (threshold); ≤-30 dB (goal) |

Channel imbalance | ≤-34 dB |

Residual phase error | ≤10º |

Spatial resolution (≥6 looks) | ≤ 60 m (across-track) x 50 m (along-track) |

PSLR | ≤-16 dB |

ISLR | ≤-9 dB |

Noise equivalent σ0 | ≤ –27 dB (threshold); ≤ –30 dB (goal) |

Total ambiguity ratio | ≤ -18 dB |

Radiometric stability | ≤ 0.5 dB (1σ) |

Radiometric bias | ≤ 0.3 dB (1σ) |

Dynamic range | 35 dB |

Observation Principles

Biomass will be based on a P-band polarimetric SAR mission with controlled inter-orbit distances (baselines) between successive revisits to the same site. At each acquisition, the radar will measure the scattering matrix, from which the backscattering coefficients (equivalent to radar intensity) will be derived in each of the different linear polarisation combinations, i.e. HH, VV, HV & VH (where H and V stand for horizontal and vertical transmitted and received), and the inter-channel complex correlation.

For interferometric image pairs, the system will provide the complex interferometric correlation (coherence) between the images at each linear polarisation. PolInSAR (Polarimetric interferometric SAR) coherence and PolSAR (Polarimetric SAR) backscatter observations provide independent, complementary information that can be combined to give robust, consistent and accurate retrieval of biomass. In addition tomography techniques, using a multi-baseline polarimetric SAR acquisition will be used to complete the knowledge of the vertical structure of the forest (Figure 3). By exploiting these capabilities, Biomass will build up a unique archive of information about the world’s forests and their dynamics (Ref. 25).

Measurement techniques

The three measurement techniques exploited by BIOMASS and illustrated in Figure 3 yield complementary information on forest properties: 30)

1) Horizontal mapping

In polarimetric mode, after calibration and correction for ionospheric effects, each BIOMASS pixel measures the scattering matrix, from which the backscattering intensity will be derived in each of the linear polarisation combinations, i.e. HH, VV, HV & VH, where H and V stand for horizontal and vertical transmitted and received signals.

For a forest canopy, the P-band radar waves penetrate deep into the canopy, and their interaction with the structure of the forest (through volume scattering, surface scattering or double bounce scattering mechanisms) differs between polarisations. P-band SAR is particularly sensitive to large forest constituents, such as the trunk and large branches, where most of the biomass resides, and polarisations can be chosen to minimise the contribution from the ground and effects arising from topographic and soil moisture variation. Hence P-band polarimetric measurements can be used to map AGB (Above Ground Biomass), as demonstrated from airborne data for temperate & boreal forests and tropical forests.

2) Height mapping

Using repeat revisits to the same location with controlled inter-track distances, the BIOMASS SAR system will measure the polarimetric complex interferometric correlation between image pairs. Thanks to them is possible to estimate the height of scattering in the forest canopy as a function of polarisation (PolInSAR). This allows canopy height to be derived, assuming a model for the vertical structure of scatterers in the forest. Numerous airborne experiments over temperate, boreal and tropical test sites have shown that forest height can be mapped with accuracy comparable to that of airborne lidar.

A crucial factor here is that at the long wavelength used by BIOMASS, temporal coherence is preserved over much longer timescales than, for example, at L-band. This is because BIOMASS is sensitive to larger structures in the canopy, which more are more stable; in addition, the longer wavelength makes the phase less sensitive to small motions of the dominant scatterers. BIOMASS will be the first spaceborne radar sensor providing large-scale height maps using PolInSAR, although the application of the technique from space has been demonstrated using Shuttle Imaging Radar (SIR-C) L-band data.

3) 3-D mapping

The P-band frequency used by BIOMASS is low enough to ensure penetration through the entire canopy, even in dense tropical forests. As a consequence, the resolution of the vertical structure of the forest will be possible using tomographic methods from the multi-baseline acquisitions to be made by BIOMASS. This is the concept of SAR tomography, which has been implemented with airborne systems and will be available for the first time using space with the BIOMASS mission. When the vertical resolution is less than half the forest height, it is possible to split the vertical distribution of the backscatter intensity into several layers, without assuming any prior knowledge about the forest's vertical structure. As expected, the bottom layer contains mainly ground scattering and the backscatter from this layer is very weakly correlated with AGB.

However, in two different tropical forest sites in French Guiana, the backscatter from a layer at about 30 m above the ground was found to be strongly correlated with AGB, up to biomass densities of 450-500 t/ha, allowing the production of wide-area biomass maps. Findings from airborne data are expected to carry across to BIOMASS, despite the coarser spatial and vertical resolution available in BIOMASS tomography.

Mission Concept

The space segment comprises a single spacecraft carrying a P-band SAR, operating in stripmap mode in a near-polar, sun-synchronous quasi-circular frozen orbit at an altitude of 634–666 km, depending on the different mission phases. The baseline Vega launcher will inject the satellite into its target orbit. The orbit is designed to enable repeat-pass interferometric acquisitions throughout the mission’s life. The baseline is different for the interferometric (in the order of 2 km at the equator) and the tomographic phases (below 1 km at the equator).

Acquisitions are made at dawn/dusk, i.e. 06:00/18:00 local time (at the equator), to minimise the adverse influence of the ionosphere on the radar signal. The Biomass mission will last five years and will comprise a tomographic phase with a duration of 18 months followed by the interferometric phase.

The strategy for meeting the baseline requirement is based on the selection of an orbit with a ‘controlled drift’, flying the satellite in an orbit where the altitude is slightly higher or lower than that of the exact repeating orbit.

Spacecraft

The Biomass space segment comprises a single LEO (Low Earth Orbit) satellite platform carrying the SAR instrument. The SAR antenna is based on a large deployable reflector (12 m circular projected aperture) with an offset feed array and a single beam. The satellite configuration is strongly constrained by the accommodation of the very large reflector antenna inside the Vega launcher. This large antenna must be folded for launch and deployed in orbit to form a stable aperture throughout the mission’s life.

The overall configuration is compatible with COTS (Commercial-Off-The-Shelf) reflectors from the US manufacturer Harris Corporation (HC). The reflector is illuminated by a 3 x 2 array of cavity-backed circular microstrip radiators, which is mounted onto the –Y wall of the satellite at the lower end.

Harris Corporation has been selected by Airbus Defence and Space UK, the builder of the Biomass satellite, to provide a 12-meter deployable reflector and precision boom assembly for this carbon-monitoring craft. 31) The Harris deployable reflector is a major component of the SAR antenna and enables the Biomass satellite to obtain a high level of map accuracy not attainable by ground measurement techniques alone. With more than 80 reflectors in orbit, Harris is the leading supplier of large reflector apertures and deployable mesh reflector-feed antenna systems.

Launch

Biomass launched aboard a Vega-C rocket from French Guiana on 29 April 2025, at 09:15 UTC. The payload separated from the launcher's upper stage approximately one hour after liftoff, placing it in a Sun-synchronous orbit at an altitude of 666 km. 49)

Orbit

The mission's Sun-synchronous near circular dawn-dusk orbit (LTAN of 6:00/18 hours), altitude (nominal ~666 km) will depend on the different mission phases. The orbit is designed to enable repeat pass interferometric acquisitions throughout the mission’s life and minimise the impact of ionospheric disturbances. The baseline observation principle is based on double-baseline interferometric acquisitions, with a repeat cycle of 3 days.

The strategy for meeting the interferometric baseline requirement is based on the selection of an orbit with a ‘controlled drift’. The amount of drift between successive orbital cycles is chosen to match the interferometric baseline requirement. In practice, the baseline is achieved by flying the satellite in an orbit where the altitude is slightly higher or lower than that of the exact repeating orbit. Because of this small drift, the resulting orbit will have a quasi-repeat cycle of 17 days for the baseline interferometric phase.

A double-baseline interferometric mode provides two interferometric acquisitions with temporal decorrelation within the requirements to improve retrieval accuracy. This mode consists of a set of three acquisitions with a fixed baseline to retrieve the forest height, while the orbit repeat cycle is kept to a minimum to ensure good temporal coherence between acquisitions spaced by two repeat cycles.

In such a way, each of the three swaths is imaged over three repeat cycles, before the satellite is rolled to observe the next one. The complete coverage is therefore achieved by matching the overall combined interferometric swath (obtained after nine repeat cycles) of 160 km with the orbit fundamental interval, achieving an orbit repeat cycle of 3 days and global coverage in just 5 months for the baseline interferometric phase.

Mission Status

• June 23, 2025: At the 2025 Living Planet Symposium, ESA unveiled the first images from its new Biomass satellite, marking a major advancement in monitoring forests and understanding the global carbon cycle. Still in its commissioning phase, the satellite is already delivering promising data using its unique P-band synthetic aperture radar, which can penetrate forest canopies to measure woody biomass, a key indicator of carbon storage. The mission’s initial images showcase diverse environments, including tropical forests in Bolivia, where deforestation is visible, as well as northern Brazil, Indonesia, and Gabon, revealing forest structure, floodplains, and topography beneath dense vegetation. Comparisons with Sentinel-2 highlight Biomass’s ability to see below the canopy, offering more detailed insights. The satellite also demonstrated unexpected potential by capturing subsurface features in the Sahara Desert and internal ice structures in Antarctica, including the Nimrod Glacier. These early results suggest that Biomass will not only improve forest carbon monitoring but also contribute to broader environmental studies, including glaciology, desert geology, and ecosystem health, positioning it as a powerful tool for climate and Earth system science. 50)

The full collection of Biomass’ first images can be viewed here.

• April 29, 2025: ESA's Biomass mission successfully launched from Europe's Spaceport in French Guiana, aboard a Vega-C rocket. 49)

• April 10, 2025: The Biomass spacecraft was successfully loaded with 132 kg of highly volatile fuel. This fuel will power the satellite so that it can carry out the complex manoeuvres that are needed to collect crucial data on our forests.

• March 10, 2025: Biomass satefly arrived at Europe's Spaceport in French Guiana, to be prepared for liftoff on a Vega-C rocket. Biomass’ embarked upon its voyage to French Guiana on February 21, 2025, when it was carefully transported by road from the Airbus’ facilities in Toulouse to the port of Sète where the French cargo ship MN Toucan awaited its arrival. The vessel is designed especially to transport valuable space-bound cargo across the Atlantic. After almost two weeks at sea, MN Toucan arrived safe and sound in the harbour at Pariacabo – the Kourou harbour.

• April 13, 2022: The largest antenna ever tested in ESA’s Hertz radio frequency test chamber is this 5 m diameter transponder antenna, which will operate down on the ground to help calibrate the Biomass mission, which will chart all the forests on Earth. 32)

- Part of ESA’s technical heart in the Netherlands, the metal-walled ‘Hybrid European Radio Frequency and Antenna Test Zone’ chamber is shut off from all external influences. Its internal walls are studded with radio-absorbing ‘anechoic’ foam pyramids, allowing radio-frequency testing without any distorting reflections. Its name starts with ‘Hybrid’ because the chamber can assess radio signals from antennas both in localised ‘near-field’ terms or else on a ‘far-field’ basis as if the signal has crossed thousands of kilometres of space. Based in Australia, this transponder will be integrated onto a mobile positioning system inside a protective radome, allowing it to track the Biomass satellite moving across the sky. The transponder antenna will reflect radar signals from Biomass back to it, to help confirm the mission is operating optimally. The transponder was developed and built by the Italian company IDS.

• November 15, 2021: With more than 100 global leaders at COP26 (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change/Conference of Parties-21) in Glasgow, UK (conference dates: 31. October to 12. November 2021) having pledged to halt and reverse deforestation and land degradation by the end of the decade to help address the climate crisis, the health of the world’s forests is high on the political agenda. ESA’s Biomass mission will soon play a key role in delivering novel information about the state of our forests, how they are changing over time, and advance our knowledge of the carbon cycle. The mission is now in its last phases of development, having recently passed several key milestones. 34)

- The COP26 pledge on deforestation and degradation from over 100 leaders representing more than 85% of the world’s forests is good news in the battle to redress the balance between the amount of carbon dioxide emitted to the atmosphere through human activity and the amount absorbed by Earth’s carbon sinks. Forests are, of course, an important carbon sink. Measurements of forest biomass can be used as a proxy for stored carbon – but this is poorly quantified in most parts of the world. Data from the Biomass mission will reduce the major uncertainties in calculations of carbon stocks and fluxes on land, including carbon fluxes associated with land-use change, forest degradation and forest regrowth.

• April 28, 2021: With challenges imposed by the COVID pandemic, engineers building and testing ESA’s Biomass satellite have had to come up with some working methods to keep on track while adhering to safety rules. The result is that the satellite structure is not only complete but has also undergone a series of demanding tests to ensure it will withstand the rigors of liftoff – all bringing the launch of this extraordinary forest carbon mapping mission one step closer. 37) As well as the tests that simulated the vibrations and shocks of liftoff and the release of the clamp band that secures the satellite to the rocket’s launch adapter, OHB also carried out a specific ‘thermal elastic distortion’ test. The aim here is to show that the temperature variations the satellite will encounter in space will not affect its strict pointing requirements. The first indications are that these swings in temperature will not introduce any distortions that could impair the way it takes its measurements.

• February 11, 2021: Biomass, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) forest measuring satellite started taking shape at Airbus’ site in Stevenage, United Kingdom with the Structure Model Platform completed. 38)

- Assembly of the satellite’s mechanical structure could not be carried out as planned due to COVID. However between April and May 2020, the Airbus team put in place a digital solution to enable collaboration with ESA and suppliers, ensuring progress continued on the development of the satellite’s mechanical structure. Airbus teams finalised the structure build in the second half of 2020 and integration hardware onto the Structure Model Platform was completed in early January 2021. The Structure Model then moved to Airbus Toulouse for its mechanical test campaign.

• October 28, 2019: Today, ESA and Arianespace signed a contract that secured the launch of the Earth Explorer Biomass satellite. With liftoff scheduled on a Vega launch vehicle from French Guiana, this new mission is another step closer to mapping the amount of carbon stored in forests and how it changes over time through deforestation, for example. 39)

• February 12, 2019: ESA’s Biomass Earth Explorer satellite with its 12-m diameter radar antenna will pierce through woodland canopies to perform a global survey of Earth’s forests – and see how they change throughout Biomass five-year mission. 40) Trees are an integral element of our environment; they also hold clues to our collective future. Knowing the amount of carbon bound up in forest biomass will sharpen our understanding of climate change and its likely effects on the global carbon cycle.

- The Biomass mission, lasting five years, aims to map Earth's forest biomass and track changes over time, contributing to the understanding of climate change and the global carbon cycle. It uses synthetic aperture radar to create maps of tree height and volume, improving estimates of global carbon stocks. The mission relies on gallium nitride (GaN) transistors, which offer 10 times more radio frequency output than traditional semiconductors and are highly resistant to radiation, making them ideal for space. Over three years, these transistors underwent rigorous testing for performance, durability, and space readiness, including radiation testing to ensure reliability in the space environment.

• November 9, 2017: Microwave radio signals are able to pass freely through Earth’s atmosphere as well as empty space. They play a role in just about everything, including mission telemetry and telecommands, satellite services and broadcasting, navigation and timing signals and radar, along with other forms of active remote sensing. 43)

- The ESA's Biomass mission will use P-band radar to monitor tropical forests, requiring advanced solid-state amplifiers instead of bulky vacuum tube amplifiers. These amplifiers use gallium nitride (GaN) technology, developed through ESA's GREAT2 initiative. The GaN technology, although already qualified, needs to be packaged for space use to prevent electrical issues and ensure reliability through rigorous testing. The mission requires six solid-state power amplifiers (SSPAs), each containing three GaN transistors. A 6 x 6 mm prototype chip, also using GaN, integrates several functions and has demonstrated significant improvements in power output and size efficiency. System-level solutions were developed to manage challenges like heat dissipation.

• October 17, 2017: Thales Alenia Space signed a contract with Airbus Defence and Space GmbH to develop the feed array system for the antenna on the European Space Agency’s Biomass spacecraft. 44)

• October 2016: The SRR (System Requirements Review) was conducted in the summer of 2016. A successful SRR is an important step in the project’s life cycle because it begins the procurement of the individual satellite components and the build-up of the full industrial consortium. Ground-based and airborne campaigns to collect data to support the algorithm development and validation were conducted, underpinned by a study to tackle the end-to-end performance calibration of a P-band synthetic aperture radar system in the presence of the ionosphere. 45)

• May 3, 2016: ESA and Airbus Defence and Space UK signed a €229 million contract on 29 April to build the next Earth Explorer: the Biomass satellite. The satellite will provide global maps of how much carbon is stored in the world’s forests and how this stock is changing over time, mainly through the absorption of carbon dioxide, which is released from burning fossil fuels. Biomass will also provide essential support to UN treaties on the reduction of emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. 46)

- The spacecraft will carry the first spaceborne P-band synthetic aperture radar to deliver exceptionally accurate maps of tropical, temperate and boreal forest biomass that are not obtainable by ground measurement techniques. The mission will collect frequent information on global forests to determine the distribution of above-ground biomass in these forests and measure annual changes. The five-year mission will witness at least eight growth cycles in the world's forests.

- The P-band SAR will gather use all-weather imagery from space to estimate forest biomass. Biomass will also be able to measure paleo aquifers in desert regions to find new water sources in arid regions as well as contribute to observations of ice sheet dynamics, subsurface geology and forest topography. Because Biomass will see through the forest canopy to the ground, terrain height maps will be provided, improving current Digital Elevation Models in densely forested areas. Biomass data will also support REDD+(Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation), a UN climate change initiative aimed at reducing emissions due to deforestation, by systematically monitoring forests in vulnerable areas with no need for ground intervention.

Sensor Complement

P-SAR (P - Synthetic Aperture Radar)

P-SAR operates in a stripmap mode with a swath illuminated by a single antenna beam, i.e. an imaging configuration similar to that of the ERS-1/2 SAR. Global coverage is obtained by the interleaved stripmap operations among three complementary swaths as described previously. The beam re-pointing is performed through a roll maneuver of the spacecraft, as there is ample time over the poles for such operations. This solution using the spacecraft rolling was preferred over the possibility of electronic beam switching due to its simplicity (Ref. 25).

The linear transmit pulse is split in the BFN (Beam Forming Network) and routed to two parallel transmit chains and amplified. A polarisation switch is placed after the HPA, to select the transmit polarisation in each of the TRUs (Transmit/Receive Units), which delivers a peak RF power of 120 W with a 12 % duty cycle and a PRF of 3050 Hz on average. The two pairs of radiators (upper and lower) are fed separately by the respective TRUs and illuminate the reflector. Splitting the power into two parallel transmit channels helps avoid potential multipaction problems.

In reception, the echo signals from the two radiator pairs are filtered and amplified in four parallel receive chains (TRU-1: V and H and TRU-2: V and H). Those are recombined in the BFN to form the V and H signals and routed to the CEU. They are finally down-converted and digitised, followed by data compression and packetisation. As any amplitude or phase imbalances between the channels would affect the beam pattern, the channel stability is ensured by the appropriate design of the TRUs, i.e. of the HPAs and the LNAs.

An additional phase equalisation can be foreseen for compensating relative phase drifts due to ageing (included in the CEU). A limiter and an isolation switch at the LNA input protect them against possible strong interference signals. The instrument mass (including margin) is 206 kg. The maximum required DC power is 221 W and the maximum data rate is 117 Mbit/s prior to compression.

A single-offset reflector antenna system is used, consisting of a feed array and a large deployable mesh reflector with a circular projected aperture diameter of 12 m. The selected configuration is characterised by a relatively short focal length to minimise the distance between the spacecraft and the reflector. Because of this, the reflector, when illuminated by a linearly polarised spherical wave from the feed, will produce significant cross-polar radiation (12–15 dB below the co-polar peak gain) in its main beam. The main beam has the form of a difference pattern (narrow null along the principal elevation plane).

To comply with the cross-polarisation ratio requirement, a pre-compensation technique is then implemented at the level of the feed. Stacking the patches is necessary to achieve a sufficient bandwidth at the level of the feed subsystem (<10 MHz). The feed assembly is made of a multilayer sandwich structure, consisting of metalised carbon or Kevlar-fiber-reinforced plastic sheets and Kevlar honeycomb or Rohacell foam core, thus low mass. Two pairs of radiators with equal excitation are used.

The radio frequency and digital electronics of the Biomass SAR instrument use well-established technologies thanks to the low radar frequency (UHF band) and narrow system bandwidth (6 MHz). However, the combination of the low frequency and high peak RF power increases the risk of multipaction. Therefore, several specific risk-retirement activities were undertaken and specific measures were implemented in the radar front-end design.

The swath width is around 50 km, which is achievable in full-polarimetric mode at three incidences. The operating incidence range is between 23° and 35°, as required for the mission. 47)

References

1) “ESA's Next Earth Explorer Satellite,” ESA Press Release No 13-2013, May 7, 2013, URL: http://www.esa.int/For_Media/Press_Releases/ESA_s_next_Earth_Explorer_satellite

2) Florence Hélière, Franco Fois, Marco Arcioni, Paolo Bensi, Michael Fehringer, Klaus Scipal, “Key Note on Biomass: a P-band SAR Polar-Interferometric Mission Selected as 7th Earth Explorer Mission,” Proceedings of the Advanced RF Sensors and Remote Sensing Instruments-Ka-band Earth Observation Radar Missions,” (ARSI'14 & KEO'14), ESA/ESTEC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands, Nov. 4-7, 2014

3) Florence Hélière, Adriano Carbone, J. G. Nelson Fonseca, Natanael Ayllon, Andrew Barnes, Michael Fehringer, ”Biomass P-band SAR,” Proceedings of EUSAR 2016, 11th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar, Hamburg, Germany, June 6-9, 2016

4) Michael Rast, ”ESA’s Report to the 41st COSPAR Meeting,”(ESA SP-1333, June 2016), Istanbul, Turkey, July-August 2016, pp: 46-50, URL: http://esamultimedia.esa.int/multimedia/publications/SP-1333/SP-1333.pdf

5) IPCC 2007, ”Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis,” (Eds. S. Solomon et al.), Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, URL: https://archive.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/wg1/ar4-wg1-frontmatter.pdf

6) Josep G. Canadell, Corinne Le Quéré, Michael R. Raupach, Christopher B. Field, Erik T. Buitenhuis, Philippe Ciais, Thomas J. Conway, Nathan P. Gillett, R. A. Houghton, Gregg Marland, ”Contributions to accelerating atmospheric CO2 growth from economic activity, carbon intensity, and efficiency of natural sinks,” PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences), Vol. 104, No 47, Nov. 20, 2007, pp: 18866-18870, URL: http://www.pnas.org/content/104/47/18866.full.pdf

7) ”Implementation Plan for the Global Observing System for Climate in Support of the UNFCCC,” GCOS–92, WMO Technical Document No. 1219. October 2004, World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20130610000933/http://www.wmo.int/pages/prog/gcos/Publications/gcos-92_GIP.pdf

8) R. A. Houghton, Forrest Hall, Scott J. Goetz, ”Importance of biomass in the global carbon cycle,” Journal of Geophysical Research, Volume 114, Issue G2, G00E03, doi:10.1029/2009JG000935, 2009, URL: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2009JG000935/epdf

9) Shaun Quegan, “Biomass: A Mission to determine global Biomass,” NCEO/CEOI (National Centre for Earth Observation/Centre for Earth Observation Instrumentation) Joint Science Conference, Nottingham, UK, Sept 18-20, 2012, [web source no longer available]

10) T. Le Toan, S. Quegan, M. W. J. Davidson, H. Balzter, P. Paillou, K. Papathanassiou, S. Plummer, F. Rocca, S. Saatchi, H. Shugart, L. Ulander, “The BIOMASS mission: Mapping global forest biomass to better understand the terrestrial carbon cycle,” Remote Sensing of Environment, Vol. 115, Issue 11, 15 November 2011, pp. 2850–2860

11) Mathew Williams, “The BIOMASS Mission: Science and Background,” 1st BIOMASS Science Workshop, ESA/ESRIN, Frascati, Italy, Jan. 27-30, 2015, URL: [web source no longer available]

12) Thuy Le Toan and the Biomass Mission Advisory Group, “The Biomass mission - How it works, what it measures?,” 1st BIOMASS Science Workshop, ESA/ESRIN, Frascati, Italy, Jan. 27-30, 2015, URL: [web source no longer available]

13) Shaun Quegan, “Facing the scientific challenges of the BIOMASS mission,” 1st BIOMASS Science Workshop, ESA/ESRIN, Frascati, Italy, Jan. 27-30, 2015, URL: [web source no longer available]

14) João M.B. Carreiras, Shaun Quegan, Thuy Le Toan, Dinh Ho Tong Minh, Sassan S. Saatchi, Nuno Carvalhais, Markus Reichstein, Klaus Scipal, ”Coverage of high biomass forests by the ESA BIOMASS mission under defense restrictions,” Remote Sensing of Environment, Volume 196, July 2017, Pages 154-162, URL: [web source no longer available]

15) Thomas A. R. Jenkins, Ewan D. Mackie, Robert W. Matthews, Gemma Miller, Timothy J. Randle, Miriam E. White, ”FC Woodland Carbon Code: Carbon Assessment Protocol (v2.0),” Forestry Commission, Version 2.0, 05 March 2018, URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20250522063958/https://woodlandcarboncode.org.uk/images/PDFs/WCC_CarbonAssessmentProtocol_V2.0_March2018.pdf

16) S. Mermoz, M. Rejou-Mechain, L. Villard, T. Le Toan, V. Rossi, S. Gourlet-Fleury, “Biomass of dense forests related to L-band SAR backscatter,” Proceedings of IGARSS (IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Society) 2014, Québec, Canada, July 13-18, 2014

17) “Biomass monitoring mission for Carbon Assessment (BIOMASS),” CESBIO, 2013, URL: http://www.cesbio.ups-tlse.fr/us/indexbiomass.html

18) K. Scipal, M. Arcioni, J. Chave, J. Dall, F. Fois, T. LeToan, C-C. Lin, K. Papathanassiou, S. Quegan, F. Rocca, S. Saatchi, H. Shugart, L. Ulander, M. Williams, “The BIOMASS Mission- An ESA Earth Explorer Candidate to Measure the BIOMASS of the Earth's Forests,” Proceedings of IGARSS (IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium) 2010, Honolulu, HI, USA, July 25-30, 2010, URL: http://orbit.dtu.dk/files/5222627/D36048EEd01.pdf

19) Klaus Scipal, Marco Arcioni, “Report for Mission Selection: Biomass,” ESA, SP-1324/1, May 2012, URL: http://esamultimedia.esa.int/docs/EarthObservation/SP1324-1_BIOMASSr.pdf

20) K. Fletcher, H. Rider, D. Wishart, “Report for Mission Selection: Biomass,” ESA SP-1324/1, May 2012, URL: http://esamultimedia.esa.int/docs/EarthObservation/SP1324-1_BIOMASSr.pdf

21) “ESA's Biomass satellite goes ahead,” ESA, Feb. 19, 2015, URL: http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Observing_the_Earth/ESA_s_Biomass_satellite_goes_ahead

22) ”Ready to build the BIOMASS forest mission,” ESA, May 3, 2016, URL: http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Observing_the_Earth/Ready_to_build_the_Biomass_forest_mission

23) M. Arcioni, P. Bensi, F. Fois, A. Gabriele, F. Hélière, C.-C. Lin, L. Massotti, K. Scipal, “ESA's Biomass Mission System and Payload Overview,” Proceedings of the ESA Living Planet Symposium, Edinburgh, UK, Sept. 9-13, 2013, SP-722, Dec. 2013

24) Dinh Ho Tong Minh, Thuy Le Toan, Fabio Rocca, Stefano Tebaldini, Ludovic Villard, Maxime Réjou-Méchain, Jérôme Chave, “Tomographic imaging of tropical forests: perspectives for the BIOMASS Mission,” Proceedings of EUSAR 2014 (10th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar), Berlin, Germany, June 3-5, 2014

25) Florence Hélière, Franco Fois, Marco Arcioni, Paolo Bensi, Michael Fehringer, Klaus Scipal, “Biomass P-band SAR interferometric mission selected as 7th Earth Explorer Mission,” Proceedings of EUSAR 2014 (10th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar), Berlin, Germany, June 3-5, 2014

26) Stephan Strauss, Charlotte Bewick, Vilfrido Lo Rizzo, Rolf Janovsky, Frank te Hennepe, Stefania Cornara, Giorgio Trinchero, Paolo Valle, Giuseppe Orlando, “System design challenges using P-band SAR observations from low Earth orbit for the Biomass mission,” Proceedings of the 65th International Astronautical Congress (IAC 2014), Toronto, Canada, Sept. 29-Oct. 3, 2014, paper: IAC-14.B1.2.10

27) “BIOMASS 2015 Program,” 1st BIOMASS Science Workshop, ESA/ESRIN, Frascati, Italy, Jan. 27-30, 2015, URL: [web source no longer available]

28) M. Arcioni, P. Bensi, M. Fehringer, F. Fois, F. Heliere, K. Scipal, “The Biomass Mission, status of the satellite system,” 1st BIOMASS Science Workshop, ESA/ESRIN, Frascati, Italy, Jan. 27-30, 2015, URL: [web source no longer available]

29) Philippe Paillou, Jorgen Dall, Klaus Scipal, “The BIOMASS Mission: Secondary Objectives,” 1st BIOMASS Science Workshop, ESA/ESRIN, Frascati, Italy, Jan. 27-30, 2015, URL: [web source no longer available]

30) Shaun Quegan, Thuy Le Toan, “The BIOMASS mission: a step forward in qualifying the Earth's carbon balance,” Proceedings of the IGARSS (International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium) 2015, Milan, Italy, July 26-31, 2015

31) ”A Reflection Of Harris Expertise For Airbus UK,” Satnews Daily, July 28, 2016, URL: http://www.satnews.com/story.php?number=1684061282

32) ”Radio eye on tree-counting Biomass,” ESA Enabling & Support, 13 April 2022, URL: https://www.esa.int/ESA_Multimedia/Images/2022/04/Radio_eye_on_tree-counting_Biomass

33) ”Forecasting performance of a space antenna – before it gets built,” ESA Enabling & Support, 26 January 2022, URL: https://www.esa.int/Enabling_Support/Space_Engineering_Technology/Forecasting_performance_of_a_space_antenna_before_it_gets_built

34) ”ESA’s Biomass on track to target forests,” ESA Applications, 15 November 2021, URL: https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/Biomass/ESA_s_Biomass_on_track_to_target_forests

35) Luciana V. Gatti, Luana S. Basso, John B. Miller, Manuel Gloor, Lucas Gatti Domingues, Henrique L. G. Cassol, Graciela Tejada, Luiz E. O. C. Aragão, Carlos Nobre, Wouter Peters, Luciano Marani, Egidio Arai, Alber H. Sanches, Sergio M. Corrêa, Liana Anderson, Celso Von Randow, Caio S. C. Correia, Stephane P. Crispim & Raiane A. L. Neves, ”Amazonia as a carbon source linked to deforestation and climate change,” Nature, Vol. 595, pp: 388-393, Published: 14 July 2021, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03629-6

36) ”The Biomass satellite and disappearing ‘football fields’,” Airbus News, 22 September 2021, URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20211023165850/https://www.airbus.com/newsroom/news/en/2021/09/The-Biomass-satellite-and-disappearing-football-fields.html

37) ”Forest measuring satellite passes tests with flying colors,” ESA Applications, 28 April 2021, URL: https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/Biomass/Forest_measuring_satellite_passes_tests_with_flying_colours

38) ”Biomass forest sensing satellite shaping up,” Airbus Press Release, 11 February 2021, URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20211016151625/https://www.airbus.com/newsroom/press-releases/en/2021/02/biomass-forest-sensing-satellite-shaping-up.html

39) ”Contract seals deal for Biomass satellite’s ride into space,” ESA / Applications / Observing the Earth, 28 October 2019, URL: https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/Contract_seals_deal_for_Biomass_satellite_s_ride_into_space

40) ”Biomass mission,” ESA, Technology image of the week, 12 February 2019, URL: http://m.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images/2019/02/Biomass_mission

41) ”Key components of tree-counting Biomass radar cleared for space,” ESA, 16 October 2018, URL: http://m.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Engineering_Technology/Key_components_of_tree-counting_Biomass_radar_cleared_for_space

42) ”P-band radar piercing through forest canopy,” ESA, URL: http://m.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images/2018/10/P-band_radar_piercing_through_forest_canopy

43) ”Delivering signal power to cross space,” ESA, 9 Nov. 2017, URL: http://m.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Engineering_Technology/Talking_technology/Delivering_signal_power_to_cross_space

44) ”Thales Alenia Space Measures Up to Win Contract for ESA Measuring Biomass” Satnews Daily, Oct. 17, 2017, URL: http://www.satnews.com/story.php?number=1619283488

45) ”Biomass status,” ESA Bulletin No 165-168, Oct. 2016, published in January 2017, URL: http://esamultimedia.esa.int/multimedia/publications/ESA-Bulletin-165-168/offline/download.pdf

46) ”Ready to build the Biomass forest mission,” ESA, May 3, 2016, URL: http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Observing_the_Earth/Ready_to_build_the_Biomass_forest_mission

47) Sophie Ramongassié, Paolo Valle, Giuseppe Orlando, Pier Giorgio Arpesi, Florence Helière, Marco Arcioni, “P-band SAR instrument for BIOMASS,” Proceedings of EUSAR 2014 (10th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar), Berlin, Germany, June 3-5, 2014

48) Margarita Naranjo, Antonio Montesano, Fernando Monjas, Mario Gómez, Rodrigo Manrique, Florence Hélière, Kees Van’t Klooster, “BIOMASS P-band SAR Reflector Antenna - Feed S/S Breadboarding,” Proceedings of EUSAR 2014 (10th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar), Berlin, Germany, June 3-5, 2014

49) "Biomass takes to the skies," ESA, April 29, 2025, URL: https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/FutureEO/Biomass/Biomass_launched_to_count_forest_carbon

50) ESA, “Biomass satellite returns striking first images of forests and more”, June 23, 2025, URL: https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/FutureEO/Biomass/Biomass_satellite_returns_striking_first_images_of_forests_and_more